‘It felt like my soul being ripped out of me’: The devastation of losing a gay twin

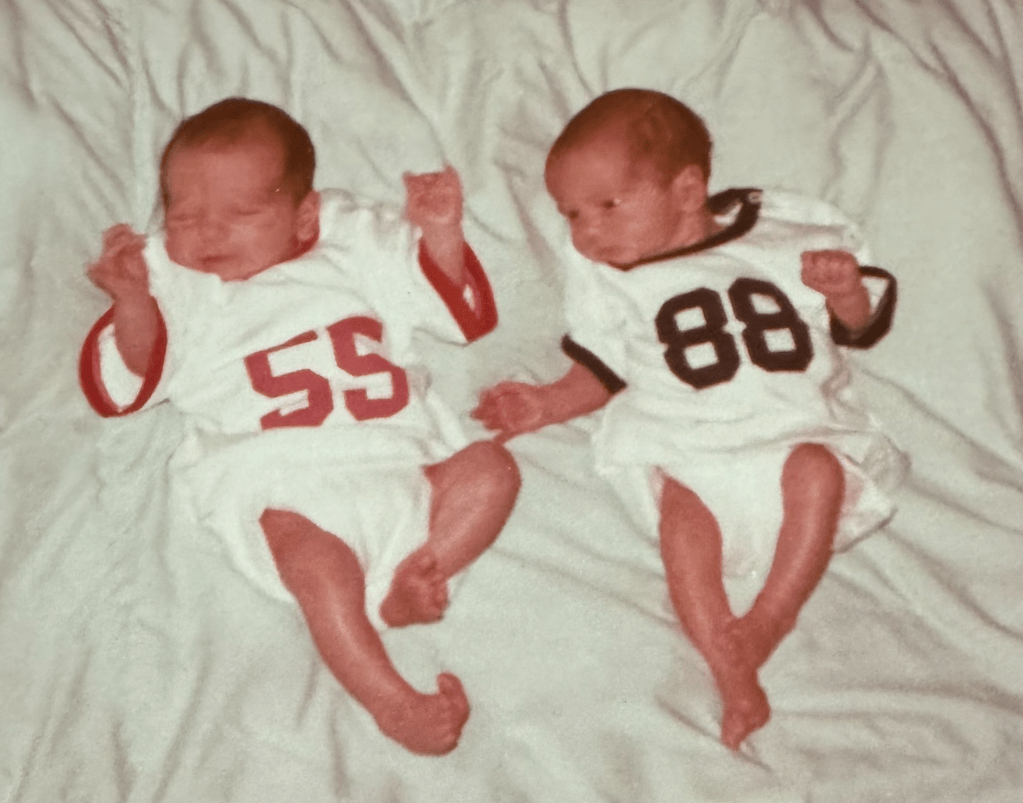

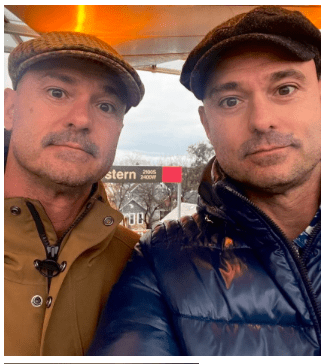

‘It never has been just me’: Scott Hinkle lost his twin Brian – Bob, as he knew him – in 2023. (Supplied)

Growing up, there were tangible ways that Scott and Brian Hinkle experienced their twinness.

Their mother dressed Brian, or Bob as Scott knew him, in blue; Scott wore red. Bob had a mole by his left eye; Scott didn’t. Until they were 15, people in their tiny Nebraska town didn’t refer to them as individuals. They were the Hinkle twins. “It was always we,” Scott says. “We spoke as we.”

There were cosmic, more brilliant experiences too. Telling a story, they could deliver a line each in quick succession, no rehearsal necessary. As they got older, gray hairs grew in the same place at the same time. A while back, Scott developed the sickly-sweet habit of squirting syrup into a jar of peanut butter, giving it a stir, and eating it with a spoon. “My brother and I never talked about it,” Scott says. Then, on a trip to Chicago to see Bob, Scott spotted peanut butter and syrup on his kitchen counter. “I go, ‘Are you just pouring that in there?’ And he goes, ‘Oh my God, it’s so good.’ And I go, ‘It’s delicious.’”

As twins, their connection exceeded the physical. “It’s this feeling of connection and uniqueness and almost a greater sense of it’s not just me. It never has been just me,” Scott says. “That’s the whole thing. It’s us and us together.”

On the morning of 31 December 2023, while on holiday at Disney World in Florida, Bob was found dead. He was 46. He had struggled with binge drinking, and after an evening consuming vodka, his blood pressure dropped to a perilous level and he never regained consciousness.

How can you begin to describe learning you’ve lost your identical twin? “It’s hard to explain.” Scott pauses, trying to put the incomprehensible into words. “It felt like my soul and heart being ripped out of me. And then, kind of just terror.”

Born in 1977, Bob Hinkle grew up gregarious. “People would meet me and be like, ‘Oh my gosh, you have such positive energy!’ And I was like, ‘Wait until you meet my brother…’” He worked as a personal trainer, focussing on encouraging older people to stay mobile, and was a trained dancer, believing that movement could connect people and bring them out of their shells. “I mean, he was a people person. He loved a party.”

Bob, “bold and brave” – or “fiercely unique”, as one friend described him at his funeral, where bright colours were worn – was the first out gay person in the twins’ rural childhood neighbourhood, though he waited until he left for Chicago for college before coming out. There, he found his community, lived a “very much unapologetically gay” life, and bonded with older LGBTQ+ folk. “He dated and only dated bears,” Scott smiles.

In Twinless, a new film by James Sweeney, Dylan O’Brien gives a stirring performance as two twins, one of whom, Rocky, has died in a tragic accident. Rocky was gay; the surviving twin, Roman, is straight. Their relationship was ruptured in part by their differing sexualities and Roman’s grief is imbued with guilt. Scott too is heterosexual, though his and Bob’s relationship wasn’t splintered by Bob being gay. In a strange way, it was one of the few things that differentiated them but was intrinsic to their bond. “Actually,” Scott says, “him being straight would just be weird.”

Scott was shocked when Bob came out, though he needn’t have been. His school folders were adorned with photos of Naomi Campbell, and he loved nothing more than watching lumberjack and strongman competitions on TV. He’d never had a girlfriend. “He was a gold star gay,” Scott says.

In the early years of Bob coming out, Scott was “almost like the gay interpreter” for friends and family members who were uncomfortable talking about sexuality with Bob directly. Scott learned quickly about the absurdity of homophobia – “society wouldn’t persecute somebody for having blue eyes” – and was inspired by Bob to be curious about those with different life paths to his own. It sent him off travelling. He now lives in Brighton, England. “Being around his way of seeing the world, I think put me on a path of exploration, I would say,” he says. What a gift he left you with, I tell him. “I’m glad that you said that. I always felt like it was a gift.”

Scott and Bob spent several years living together in Chicago, and Scott slotted in easily among Bob’s gang of gay friends. “There would be times where I would be the only straight guy at loads of different events, parties, bear barbecues. I loved it, right? It made me feel privileged,” he says. Scott became close with Bob’s boyfriends; as a straight presence, he was safe. “I always felt like the gay aspect was a gift,” he says. “I desperately miss the connection to the gay community.” For the first time in our conversation, Scott’s eyes brim with tears. He takes a second, continues. “Crying is part of my existence now. It’s part of being a lone twin for me. Touching the grief is important.”

After Bob died, Scott spent three days in bed. His first time out of bed, he saw a photo collage of them growing up, up in his living room. “That was my first panic attack I’ve ever had.” A blurry period of “crippling devastation, anxiety” and “living in terror all the time” followed. Even seeing someone who fitted Bob’s type was a trigger. “For the first six months I would be at an airport and see a giant man and start crying. I mean, that’s not great.”

Over time, terror subsided into anger – at Bob, at himself – before ossifying into a profound sense of loss that can only be experienced by someone who has lost a twin. “A loss of identity. I don’t feel like a whole person anymore. I’ve definitely lost my spark.” His voice shakes. “Honestly, I feel like I’ve lost some of my masculinity, my assertiveness, my boundaries, my emotional resilience.” Bob had the latter in spadeloads. “So it feels like it just sort of has been taken away. Not only am I dealing with the loss of him and us, but I’m also like, who am I now?”

In Twinless, Roman attends a support group for twinless twins. Eight months after Bob died, Scott did so too, heading to his first Lone Twin Network meeting. The organisation offers group support to those who have lost a twin at any stage in life, from birth to late adulthood. “You don’t have to explain what being a twin is like and you don’t have to explain what losing a twin is like,” Scott explains. “It just is a place where you don’t have to explain s***, right?”

During his first meeting, Scott shared his story. In meetings since, he’s listened to and supported others. It’s been therapeutic. So too has the massage therapist who specialises in assuaging the physical strain of grief. And his new, intense gym routine. And the men’s community group he’s now part of, which provides mentorship to young men, many of whom have been in the criminal justice system. “Our whole focus is about helping people express and process anger, fear, love,” he says. “Anybody that shows up can bring an issue that they have. So I brought mine and it was an evening that I’ll never forget. They allowed me to say goodbye in any way I wanted to.”

Of course, grief is no bow-tied process where one emotion evaporates, never to be felt again. Time doesn’t heal grief, just “makes it more palatable and [strengthens] your ability to live in it”. Scott says his capacity for emotion has expanded, but his capacity for joy has shrunk. “That doesn’t make any sense.” So he’s actively trying to invite joy into his life. Bob wasn’t judgemental, so Scott is honouring his twin by removing judgement from his life. Bob loved house music, so Scott plays it while working out. Bob introduced him to the gay community, so Scott is looking for ways to reconnect with it in an “authentic, meaningful way”.

There is a practical way that he expresses his loss and stays close to Bob too. “I created a book that people could write in. I write messages to him,” he says.

“So then on our birthday and then around the day that he died, I just journal to him. I think one of the things that I’ve been talking about is the different phases of grief that I went through. Now I’m in a phase [where] I want to be intentional about feeling love and joy not only towards him, but towards the relationship that we had.”

Twinless is in UK & Irish cinemas 6 February. For cinemas visit: PARK CIRCUS.

Share your thoughts! Let us know in the comments below, and remember to keep the conversation respectful.