After enduring gay ‘conversion therapy’, author Jake Johnson is finally ‘where he’s supposed to be’

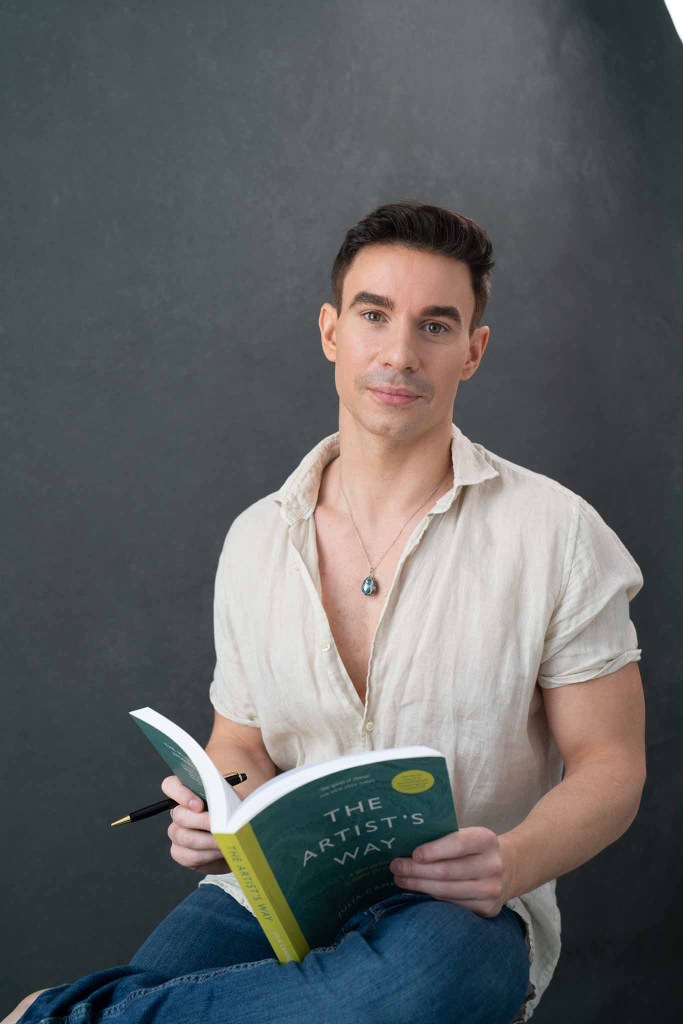

Jake Johnson shares his experience of conversion therapy (Matthew Dormor)

Jake Johnson shares his experience of conversion therapy (Matthew Dormor)

Jake Johnson never imagined being a writer. Growing up in Seattle with undiagnosed ADHD and dyslexia it seemed like the furthest idea from reality.

Cut to 2025 and his first book, The Giving Home, has just been published with four more on the way.

But the journey from one point to the other, as it soften is, has not been straightforward. And in Jake’s case, has involved a great deal of pain. But it’s these experiences that have shaped the author that Jake is today.

In The Giving Home, a recently single and unemployed Caroline embarks upon a healing journey of self-discovery after returning to Amsterdam.

Similarly, Jake, in moving to London, giving up a job with Amazon, and embarking upon his own journey of connection and love – things that proved elusive to him for the longest time – has found himself mirroring his protagonist. “Writing was like therapy,” he says as we chat over Zoom.

But because of everything that has happened to Jake, “the parts that were super rewarding were the moments of emotion and self-discovery I had for myself,” he adds.

Jake grew up in Medina, a conservative part of Seattle. There were “good bits and bad bits” – a conversational-small-talk way of saying lots without saying much.

He grew up in a supportive household. But for one reason or another, he was felt ‘othered’ beginning a long cycle of never feeling like he had a community of his own.

A “rambunctious kid,” Jake was on a dizzying cocktail of drugs including Wellbutrin, Prozac, and Lithium for his at times “unmanageable” ADHD. Between that and what he now recognises as a burgeoning queerness he wasn’t someone to associate with. And in Medina, image was everything.

It would be easy to judge parents for throwing medication at a young child. Jake doesn’t though. “They were just trying to find some way to get me to calm down,” he says. He admits his memories of his early years are blurred likely thanks to the medication but recalls his schoolwork suffering.

The middle of five boys, one of his older brothers was sent to a camp for anger management issues and came back reformed. Having tried most things, his parents thought a similar camp could help Jake.

So, at nine years old Jake was shipped off to Majestic Ranch, in Randolph, Utah, a deeply religious state where approximately 63% of adults identify as Christian (mostly Mormons) Jake would spend three years here.

Information on the now-closed ranch is hard to come by and it seemingly last recognised as the Old West Academy, which reportedly shut for good in 2019. But what there is shows it was marketed as being for children aged 7-14 with “behavioural issues,” and possibly part of the controversial World Wide Association of Specialty Programs and Schools group.

Mornings were for classes, some involving religious teachings, in which Jake remembers having to write essay after essay about why it was wrong to like boys in the hope the message would sink in. Jake was then “coached” to believe that being gay was wrong and harmful to himself, as well as others.

“They’d build these lies on top – I won’t be able to go home [unless I change], that I’m a danger to my family, people won’t love me, I’m going to go to hell.”

In the afternoons Jake and the other campers, a mixture of boys and girls and ages who were there for reasons ranging from sexuality to anger management, provided free labour around the ranch.

Other sessions saw Jake have to create a paper mâché representing himself including his attraction to boys. These were then symbolically burned. “This is you removing this part of yourself,” he was told.

Jake says he was physically, sexually and mentally abused while there – mostly by the older boys, but on one occasion by one of two adult therapists.

“Anytime those incidents occurred, anybody involved was reprimanded,” Jake shares. Even when it was a member of staff abusing Jake, “I would get in trouble for that,” he says.

Meanwhile his parents, he later found out, were fed specific information. Communication was monitored. None of the letters he wrote begging to be brought home were ever received.

“I truly felt abandoned,” he says with another loud exhale. His interactions with the other boys confused sex for him. “These people want me, they’re making my body feel good, and I’m getting reprimanded for people trying to show me love.”

After three years he was moved to another facility in Logan, Utah. Whereas before Jake had wide open spaces to run around in, now he was trapped inside a building with only a small yard to do for outdoor space.

And now Jake was surrounded by other boys thought to be in need of ‘converting’, but also boys who had abused other children.

“I remember feeling utterly defeated,” Jake says of the transition. “Any sense of me trying to do good in my mind was gone. I became very angry.”

As well as the company he now kept, classes reinforced a painfully inaccurate and harmful conflation of homosexuality and child abuse. On top of that, Jake was abused further.

It had been made clear to Jake that he was in Logan for a year. This meant his parents had to find somewhere else for him to go, believing he still wasn’t making any progress.

While touring a new facility nearby with his mum Jake saw one of his abusers and “lost my shit.” He recounts, “I was like ‘I will not survive if I go to this place’. My mum was like, ‘what’s going on?’ I told her who was in there and what had happened.

“My parents had no clue that any of this abuse was occurring. And she took me home.” Jake was 13.

Jake reiterates that ‘conversion therapy’ was never his parents’ focus. In the haze of everything going on at home, his sexuality had been hard for anyone to see. His parents had just wanted to find a solution for what they could see.

At home, now 14, Jake, tried sleeping with a woman. Even this encounter was laced with ideas of converting Jake. “She knew I was gay, and she was like ‘I can help’.”

However, it got Jake to come out, and in doing so begin claiming his identity. He was able to find community in Seattle. Though the freedom Jake had was also confusing.

“What I don’t know if a lot of people understand is that when you try to integrate a kid back into society who’s been told their whole identity is wrong, that identity dysmorphia is really damaging.”

And like the proverbial rose Jake has grown from his experiences learning empathy, curiosity as well as defiance. He’s also learned how to manage his ADHD, something he nor anyone else deemed possible before.

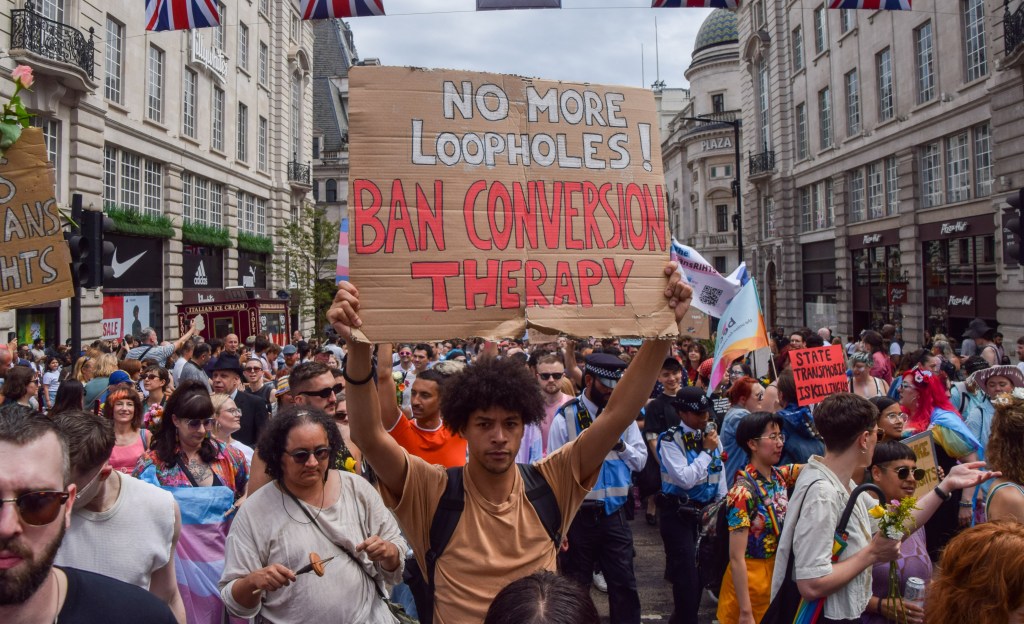

Here in the UK, we’re still waiting on a full and inclusive ‘conversion therapy’ ban. Despite one first being promised back in 2018, efforts to get one through parliament have ultimately failed. And despite a change of government, we don’t seem any closer.

“It’s horrible that these programmes are still around,” says Jake. “It shows how much religion is still baked into communities. Also, I don’t think there’s been enough information out there for governments to take this up.”

Asked what information he thinks is needed, he replies: “Stories like this. You’re really damaging the psyche of these young adults, and I think the fact that there are people who are willing to sign up to go to these camps shows there’s a lack of understanding for who they are as well. My heart goes out to those individuals who feel like this is a viable route for them.”

Jake also advocates for more therapists that work specifically with the queer community as well as funding from governments for organisations like America’s Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG) to support parents as well.

Bringing it back to The Giving Home, Jake explains that his time in ‘conversion therapy’ delayed him being who he was meant to be.

“I would have become an author earlier on,” he states confidently. “And I would have gone to college if I wasn’t spending so much time trying to understand who I am and find connection.

“I got to where I was supposed to be eventually. It just took me an extra decade because I spent so much time playing catch up on the identity part of myself.”

The Giving Home is out now.