Chloe Michelle Howarth on obsession, repression and writing queerness into 60s Ireland

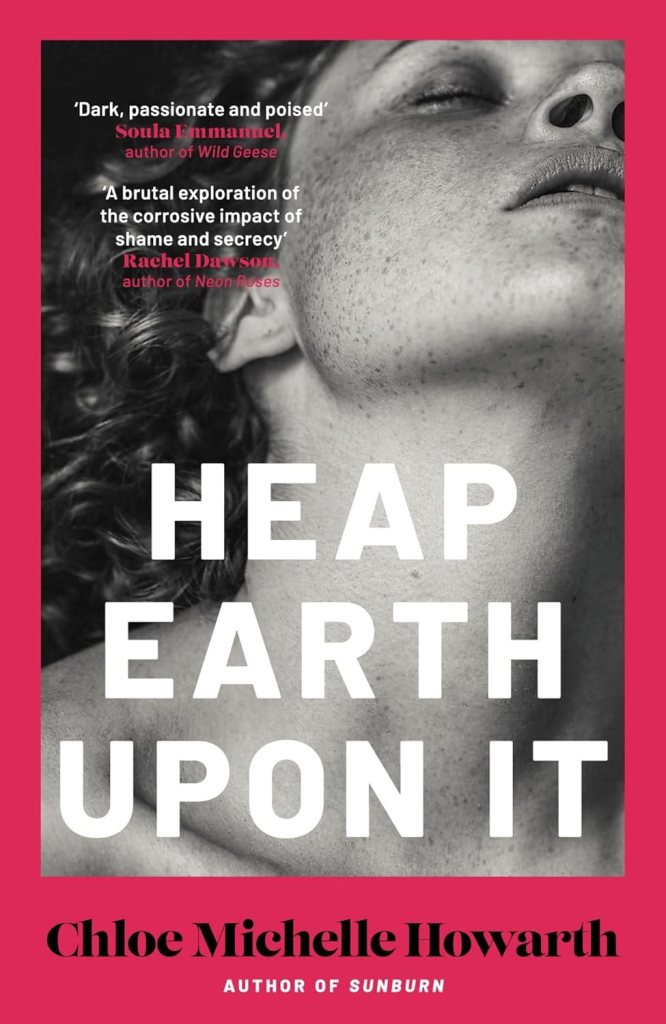

Heap Earth Upon It (VERVE Books)

Following her acclaimed first novel, Sunburn, author Chloe Michelle Howarth has returned to rural Ireland with Heap Earth Upon It, a gothic-tinted family drama set in the 60s.

PinkNews caught up with Howarth to talk obsession, repression and writing queerness into mid-20th century Ireland…

For readers new to your work, how would you pitch the new book in one or two sentences?

It’s a multi-perspective family drama set in rural Ireland in the 1960s. There’s sapphic obsession, repression, a creeping sense of dread and a village that isn’t sure what to do with the strange, wounded family who suddenly arrive [there].

What drew you back to rural Ireland as the setting and what felt different about writing it this time around compared with Sunburn?

I gravitate to rural Ireland instinctively. With Sunburn, I was writing the 90s, which is my own landscape. But the 1960s, though only 30 years earlier, required so much excavation. Everything had to be researched, down to what was in the kitchen drawers.

I wrote Heap Earth in England, and that distance romanticised the place even more. I binged old (TV station) RTE archives, village fetes, farms, Sunday-best performances, to make sure the village carried that mixture of beauty and threat.

Where does the title come from and when did you know it was right?

It comes from that old phrase: the sense of burying something completely, letting it sink and rot. The moment I realised what the novel was really about, what we try to push down: desire, shame, history, I knew it had to be the title.

The atmosphere is suffocating in the best way. What research helped you build that sense of claustrophobia?

It was less “what happens” and more how close everyone is. In those villages, you don’t need violence to feel trapped. You need teacups, curtains and neighbours who always know where you’ve been.

How did you create tension without tipping into melodrama?

I rewrote constantly. I added layers to the story rather than heightening the drama, and the shifting perspectives help. We don’t sit inside one person’s spiralling long enough for it to become overwrought. Just when someone is on the brink of emotional excess, we move.

The point of view is so controlled. Did that structure change during revisions?

Dramatically. I drafted the book several times, making each sibling the protagonist. I had to live inside all of them before deciding whose story moments mattered. I even considered Bill’s perspective at one point but ultimately Betty’s voice was essential too. She anchors the danger and the hope.

Bill and Betty, the siblings’ new neighbours, are catalysts throughout the story. How did you make sure they were their own characters?

They couldn’t just be plot devices. They needed dignity, their own disappointments and tenderness. They’ve longed for children. The siblings arrive and awaken that desire. That’s where the danger lies.

Writing queerness into 60s Ireland carries a lot of social weight. What historical constraints shaped that and what did you choose to subvert?

The biggest constraint was silence. There wasn’t a vocabulary for queerness, no mirror to recognise yourself in. Anna isn’t repressed because she’s “wrong”, she’s terrified because she has no language. I loved subverting the expectation that queerness would be the scandal. For Betty, the problem isn’t Anna’s crush, it’s the consequences of secrecy and upbringing. Queerness itself isn’t the danger, the world around it is.

Anna’s queerness feels ghostly. Was that intentional?

Yes. Queerness then was often experienced like that. She’s reaching without knowing what she’s reaching for.

Desire in the novel feels sacred and dangerous. How did you approach writing intimacy under surveillance?

I love yearning, I love longing: those sacred, unbearable little gestures. Desire becomes almost a secret. Shame is part of it too. Tom’s desperation for Bill’s approval, for instance, feels almost holy to him.

Finally, can you give us three words that describe the book’s after taste?

Earthy, boggy, copper. Like blood on the tongue.

Heap Earth Upon It is available now.

Share your thoughts! Let us know in the comments below, and remember to keep the conversation respectful.