Virginia Woolf’s undying, tragic queer romance inspired one of history’s most radical books

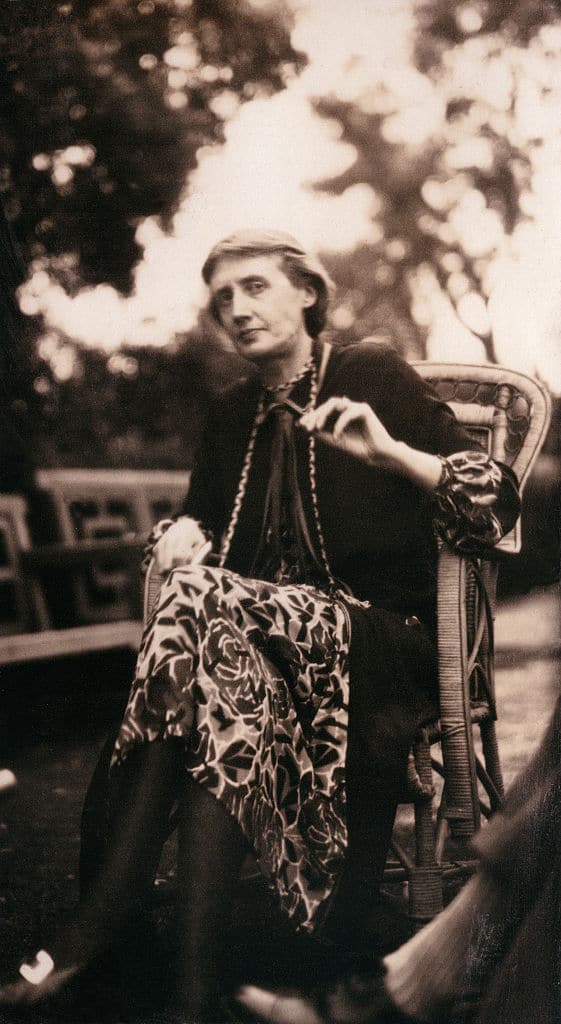

Virginia Woolf. (Getty)

On 14 December 1922, Virginia Woolf met Vita Sackville-West for the first time. In the years that followed, they developed an intense love for one another – and that love influenced both their lives and their writings.

The romantic and sexual relationship between Woolf and Sackville-West has gotten plenty of attention from literary critics and scholars in recent years, and it’s not hard to see why. Their partnership inspired Woolf to create some of her most groundbreaking, acclaimed work.

For Virginia Woolf, it formed the foundation for her deeply subversive novel Orlando, which tells the story of a man who transforms into a woman and lives for 300 years. To this day, it remains a powerful and transgressive meditation on gender and sexuality.

Like her contemporaries, Woolf didn’t become a radical queer writer overnight. It was a long, often drawn out process in which she explored her own identity, her sexuality and her gender over the course of several decades. Woolf’s life famously ended in tragic circumstances, but to say she had a remarkable life would be an understatement.

Virginia Woolf was born Adeline Virginia Stephen on 25 January 1882. Her father, Leslie Stephen, was a writer and critic, while her mother Julia Stephen was a pre-Raphaelite model and philanthropist. From the start, Woolf benefited from being born into wealth. She was afforded an education at a time when many people, particularly women, were denied that right.

Uniquely for that time, Woolf was encouraged by her parents to write. Neither her father nor her mother believed in formal education for women, but writing was at that time considered a respectable line of work for a woman of her class and stature in society. She was a voracious reader and writer from an early age, and that paved the way for her to explore her innermost thoughts and ideas on the page.

Virginia Woolf was part of the radical ‘Bloomsbury Group’ in London

Her early years were characterised by a series of losses that devastated the young writer and led to her experiencing severe bouts of depression. After surviving a suicide attempt, Woolf and her sister Vanessa moved to 46 Gordon Square in Bloomsbury, and it was there that they became acquainted with the group of intellectuals that would later come to be known as the Bloomsbury Group.

In 1912, Woolf married her husband Leonard Woolf, and three years later she published her debut novel, The Voyage Out, which satirised Edwardian life. That same year, they moved to Hogarth House on Paradise Road, which would later serve as the name for their publishing house Hogarth Press.

All of these events were highly influential in Woolf’s writing, but it was her relationship with Sackville-West that encouraged her to explore her own sexuality and inner life in new, groundbreaking ways. Before long, the pair began a sexual relationship, and that period paved the way for Woolf to create some of her most significant works. During that same period, Woolf was known to brag to friends about her intimate relationships with women such as Sibyl Comefax and Comtesse de Polignac.

In 1927, Woolf published To the Lighthouse, and a year later, Orlando – possibly her most radical work – was released to the world. Sackville-West’s son Nigel Nicolson later wrote: “The effect of Vita on Virginia is all contained in Orlando, the longest and most charming love letter in literature, in which she explores Vita, weaves her in and out of the centuries, tosses her from one sex to the other, plays with her, dresses her in furs, lace and emeralds, teases her, flirts with her, drops a veil of mist around her.”

She also wrote a number of influential essays in that era, such as “Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown” and “A Letter to a Young Poet” – but the period was also characterised by Woolf’s mental health issues. She had suffered from bouts of depression and suicidal ideation throughout her life, but the situation appeared to become progressively worse as the years rolled by. Her relationship with Sackville-West seems to have lifted her spirits – she appeared to be more confident, both in herself but also in her work, than she had previously been.

Sadly, those efforts were not to last. There has been ardent speculation throughout the years about Woolf’s mental health – some psychiatrists have since suggested that she could have been suffering from bipolar disorder at a time when such an illness was not recognised nor was it treated correctly. Her depression was exacerbated by grief for those she had lost, including her parents, but it was likely made worse by the doctors who blamed her education and her passion for reading. It was Sackville-West who suggested that Woolf had been misdiagnosed, and that reading and writing would help calm her nerves rather than make them worse.

Woolf died by suicide, feeling that she was ‘going mad again’

In 28 March 1941, Woolf tragically died after drowning in the River Ouse. In her suicide note to her husband, she wrote that she was “going mad again”, and said she felt unable to “go through another of those terrible times”.

“I don’t think two people could have been happier till this terrible disease came,” she wrote. “I can’t fight it any longer.”

In the years since, Woolf’s legacy has been reappraised by queer theorists and feminist scholars, and she has rightly been remembered as one of the great writers of the modernist period. Time and time again, scholarship has focused on the remarkable exploration of gender and sexuality in Orlando.

In the article “Queering Time: The Temporal Body as Queer Chronotope in Virginia Woolf’s Orlando“, published in the Anglia journal, Pooja Mittal Biswas writes that the novel is cloaked in subtext because of the “sexual and literary conservatism of Woolf’s time”.

“Subversion can only occur within the system; once one is outside a system, only rebellion is possible, and that is a far less subtle – and sometimes far less effective – mode of resistance,” Biswas writes.

In many ways, that summarises Woolf’s approach to both her life and her work. She resisted the norms and expectations of the time in which she lived. She repeatedly refused to bow down to patriarchal ideas about how she should conduct herself and live her life. She also refused to repress her sexuality, as was required of women of her era.

It is this that made Woolf such a remarkable writer: she wrote for the people of her time, but she was also writing for queer people of the future, who have flocked to her work in their droves ever since.