I was bullied and abused for my ‘gay voice’. Now, it’s my most powerful tool

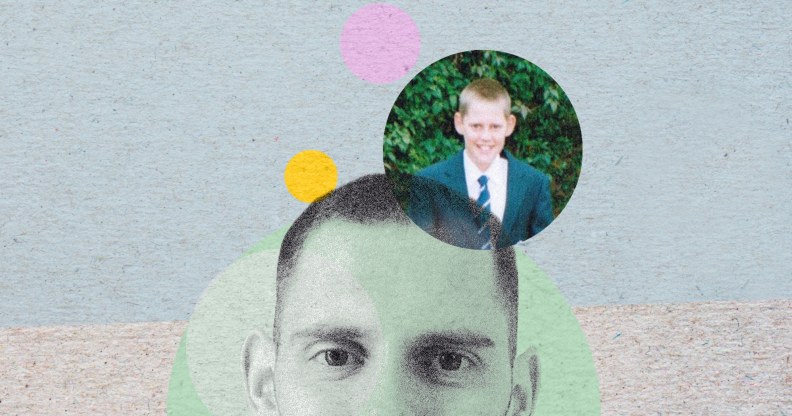

Mental health advocate Jack Dodd explains how he learned to use his ‘gay voice’ to own his story. (Jack Dodd/PinkNews)

Jack Dodd is a mental health advocate and senior corporate partnerships manager at PinkNews. On World Mental Health Day, he explains how he overcame years of trauma and learned to use his ‘gay voice’ to own his story.

Content warning: Self-harm and suicidal ideation.

It’s the summer of 2005 and I’m feeling sad that the end of Big Brother season six is on the horizon. But on the other hand, I couldn’t be more excited for my first day at secondary school.

And it seemed I wasn’t the only one who’d spent their summer watching reality TV. As everybody was getting to know each other, my new classmates were united in the hilarious observation that I reminded them of Big Brother contestant Craig. Why was this? Craig was gay. And apparently I was too.

The kids at school said that my ‘gay voice’ and my mannerisms reminded them of him. Craig was expressive and camp, and apparently so was I. So they mocked me and called me Craig.

I’d never been called gay before and I didn’t even know what it meant.

I was shocked and felt vulnerable. I’d never been called gay before and I didn’t even know what it meant. The only thing I could fathom was that it was making me stand out – and not for the right reasons. That night, my mum innocently asked me about my first day and I cried uncontrollably.

The bullying continued the next day, and the next, and the next.

To survive, I learned to filter everything that I put out into the world – from my so-called ‘gay voice’, to how I expressed myself, to even how I sneezed. I buried myself and my ‘gay voice’ all to avoid the abuse from my classmates.

It went on and on and on like this until the autumn of 2007. 26 November.

My dad dropped me off at school that morning, just like every other morning. Except this time he wasn’t there to pick me up at the end of the day. I waited for his car to pull up but my mum appeared instead and immediately asked me to hold her. I obliged, and she told me that my dad had suffered a heart attack earlier that afternoon and he had died.

He was 54.

We set off to see him at the hospital, me in floods of tears. But as I recognised some kids from school through the car window, I immediately stopped crying. Even in the wake of my dad’s death, I could keep the most authentic parts of me from showing. All to avoid attention. All to stay safe.

Hiding my true self continued to be second nature. Except now I wasn’t just hiding my ‘gay voice’ and any camp mannerisms, I was also holding back insurmountable grief. To the world, I was quiet, reserved and voiceless. On the inside, I was just numb.

I made a pact with myself that I would find out my GCSE results and then I would kill myself.

It wasn’t long before serious cracks began to show in my mental health and I started having suicidal thoughts. I remember making a pact with myself that I would find out my GCSE results and then I would kill myself.

Luckily, I didn’t follow through on this. I did begin self-harming, though. And early symptoms of anxiety and OCD started to haunt me.

Mental health issues dictated my life for many more years as I struggled to navigate not only life’s challenges, but relationships with those around me. I regularly became overwhelmed by everyday situations and I couldn’t understand what I was going through.

But things began to change when I committed to regular therapy and started taking medication, both of which opened my eyes to the full extent of my pain and I began to heal. It was if I’d been in an emotional coma for many years and I was stirring for the very first time.

It soon became clear that I’d never truly accepted myself, or my sexuality, and that I’d buried so much pain deep, deep down. My body would tremble and shake whenever my therapist asked me about my days at school and I struggled to understand why.

I was also unforgivingly critical of myself. I thought I deserved everything that had happened to me and convinced myself that my trauma wasn’t anything special. Every gay kid got bullied at school, right? And yeah, sure, my dad died. But that was years ago. Shouldn’t I be over it by now?

Mental health advocate Jack Dodd is making sure his ‘gay voice’ is being heard this World Mental Health Day. (Jack Dodd)

Unpacking my trauma has taken – and continues to take – a lot of work. Hiding every aspect of my unfiltered self meant that I didn’t know who I was. Trying to express myself felt like trying to speak in a language I didn’t understand. To this day, when I try to articulate how I’m feeling, I often feel overcome by a wave of embarrassment and self-criticism.

The thing is, I was suffering, and in trying to express my pain as part of my healing process, I was inevitably going to have to talk about it. It was a double-edged sword. The channel I was using – my ‘gay voice’ – was the very thing that stopped me from talking about how I was feeling in the first place.

It was like trying to cross a rickety old bridge while being scared of heights. It was always going to get worse before it got better. Whenever I heard my own voice trying to articulate my problems, I began to criticise myself in the same way the kids at school would bully me.

But now, I’ve grown in confidence, and in strength. Now, I use my voice to share how I’m feeling and I talk unapologetically about my experiences, and the importance of being open about mental health.

I am lucky enough to still have weekly therapy and proudly take medication to help me.

I’m happier than I’ve ever been. I’m more accepting of myself and, crucially, I understand and own my story. I’m no longer staying quiet, nor punishing myself.

This World Mental Health Day, if you are struggling, please talk to someone you trust. Use your voice, no matter how scary that feels. My ‘gay voice’ is now my most powerful and proudest tool, and it can be yours too.

Click here for more information on World Mental Health Day. If you’re struggling with your mental health and need to talk, contact Samaritans on 116 123 or Switchboard LGBT on 0300 330 0630.