Nobuko Yoshiya: Queer Japanese icon who adopted her girlfriend to get around same-sex marriage ban

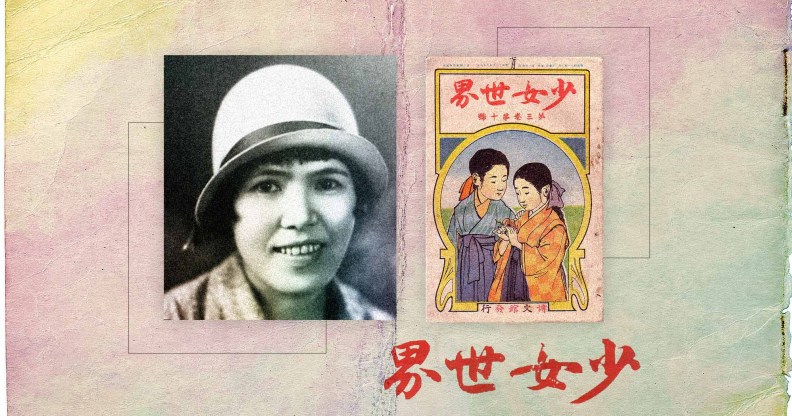

Nobuko Yoshiya’s work, which pioneered Japanese lesbian literature, laid the foundation for today’s popular shōjo manga. (Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

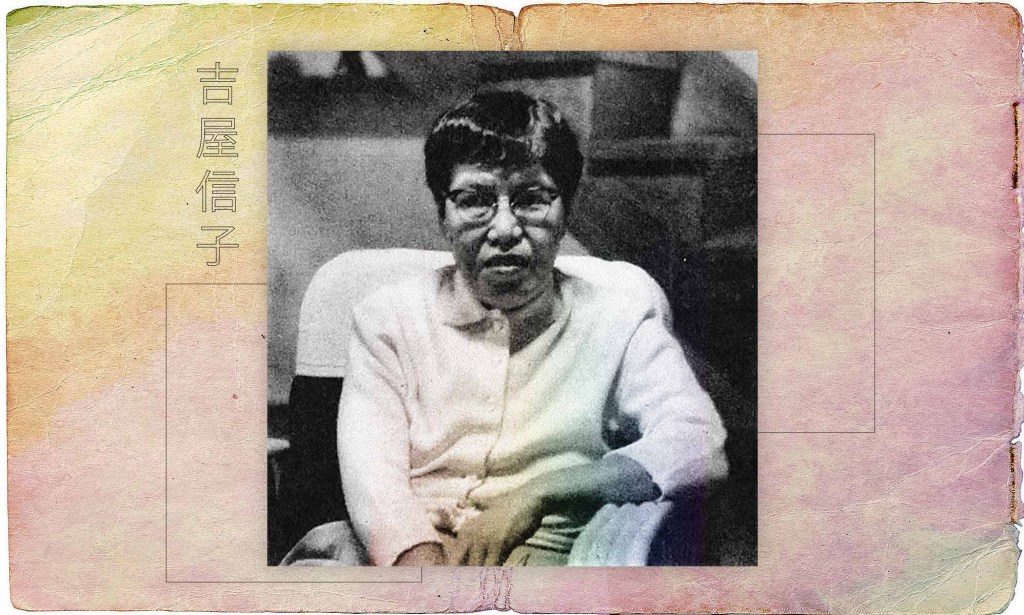

Nobuko Yoshiya became one of Japan’s most successful authors in the 20th century while putting her queerness front and centre.

Nobuko Yoshiya lived a life of revolution. In addition to pursuing an openly queer life in early 20th-century Japan, she pioneered sapphic fiction and today’s popular shōjo manga.

She was one of Japan’s most commercially successful female authors during her life time, so much so that she owned a number of homes. One of those, which she built with her partner, has since been turned into a museum dedicated to her work.

Yoshiya specialised in romance and fiction novels that focused on queer relationships between women at a time when such subjects were taboo.

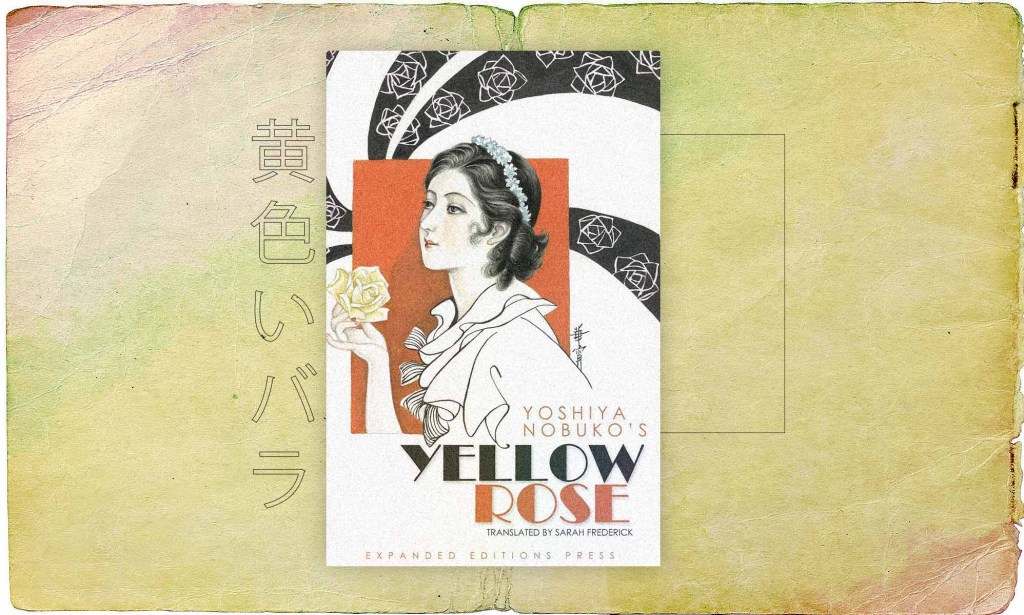

Despite all her accomplishments, her works have rarely been translated into English. But the impact of her work is felt far beyond the communities where she’s a particularly celebrated icon.

Her writing influenced one of Japan’s most wide-reaching cultural exports: manga, an umbrella term for Japanese comic books or graphic novels that centre on immersive storytelling through pictures.

Manga has an immense fan base worldwide. Some popular manga have been adapted into TV programmes, have merchandise and inspire stage productions.

Yoshiya’s work laid the foundation for shōjo manga, a category aimed at adolescent females and young adult women. The plots often touch on close female friendships that are seemingly platonic but also ambiguous enough to allow authors to avoid censorship and for queer readers to feel seen.

Much of Yoshiya’s writing championed sapphic feelings and her works’ popularity made such relationships palatable to a mass of hungry readers. Her stories also challenged traditional societal structures in Japan at a time that demanded strict adherence to gender norms.

But it wasn’t just Nobuko Yoshiya’s work that was trailblazing – it was also how she decided to live her life openly, full of love.

Nobuko Yoshiya’s life

Yoshiya was born in 1896 in Niigata, a port city on Japan’s main island Honshu. She was the only girl in a family of five children.

Her culturally conservative parents exerted pressure on Yoshiya to conform to traditional patterns of behaviour. This included gender norms, which have long positioned women as the main caretakers of their families.

In 1915, Yoshiya moved to Tokyo and began pushing back against Japan’s gender expectations.

She attended meetings of Seitō, Japan’s pioneering feminist magazine, and met other women writers carving out lives separate from the heteronormative norm.

Yoshiya changed her presentation by chopping her hair into a short bob. She also moved from wearing kimonos, skirts and dresses to adopt a more androgynous style, wearing men’s clothing.

She also began creating her literary series, Flower Tales. Written between 1916 and 1924, these included 52 stories of romantic friendships between young women and were very popular with female students.

Most of the tales depicted intense emotional relationships, filled with longing from afar, unrequited love and some chaste kisses.

Yoshiya again focused on queer love in her best-known work, Two Virgins in the Attic (1919). The love story depicted two dorm mates who move in together, discover their feelings for each other and decide to live together as a couple.

The grounbreaking work presented strong feminist themes as the characters embraced their relationship without any punishment for their transgressive sexuality, which was unusual for the time.

Although famous for her explicitly queer works, Yoshiya’s later books were notably less overt, probably a response to commercial reality and to conform to expectations of a broader audience.

Her work after Two Virgins in the Attic cut back on blatant representation of love between women and instead focused on homemakers in unhappy marriages.

In these works, the main character formed an intense but platonic bond with another woman. But whenever something resembling a queer relationship began to form, one character would suddenly end up out of the picture.

Yoshiya’s queerness may have been hidden in some of her works, but she made no secret about her personal love life.

Nobuko Yoshiya adopted the love of her life

Yoshiya met the love of her life Monma Chiyo, a 23-year-old maths teacher, in 1923. Their relationship and collaborative partnership lasted for more than five decades.

When Chiyo’s work separated the couple for 10 months, Yoshiya sent her lover a practical proposal about their future relationship in a letter.

She wrote: “1. We will build a small house for the two of us.

“2. I will become the head of household and officially adopt you.

“3. We will ask a friend to serve as a go-between, and hold a wedding reception.”

Same-sex marriage was not, and still is not, legal in Japan. Adoption was the only loophole in the country’s legal system that allowed two unrelated women to own property and make medical decisions together.

Chiyo accepted, and the couple, at least officially, became mother and daughter. They moved into a small home in Tokyo.

Later, Yoshiya’s success earned her enough royalties to own five homes. After her death in 1973, she willed her house in Kamakura to be used for women’s cultural activities, and it would later become a museum dedicated to the legendary writer.

Chiyo was at Yoshiya’s side when she died and recalled her partner’s dedication to her dreams.

“Even in her old age, Ms Yoshiya remained in pursuit of the sweet fragrance of her girlhood dreams. Perhaps that is why I was attracted to her,” Chiyo said. “The passing of 50 years is, perhaps, merely one lady’s dream.”