Stonewall veteran Mark Segal smashes offensive, ‘belittling’ myths around the 1969 riots

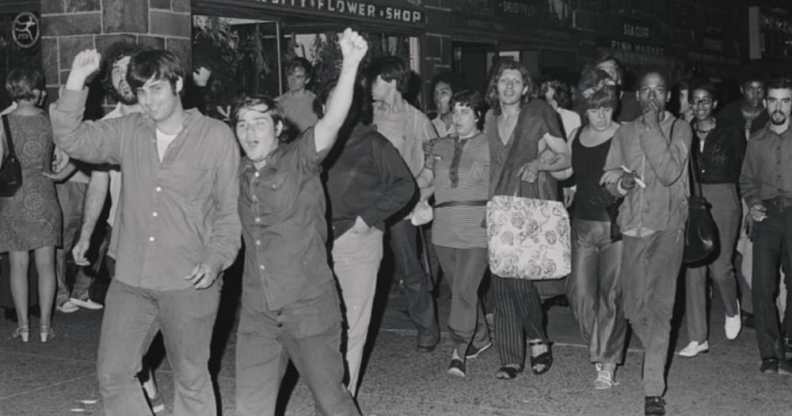

Mark at the Stonewall riots in 1969, pictured at the front with his arm raised. (Provided)

On 28 June, 1969, Mark Segal went to the Stonewall Inn to do what he loved best: dance, meet cute boys and have fun.

“That was the only place you could do that in New York as a gay man,” Mark says. “Now, the place might have been a dive, it might have been dirty, it might have served watered down drinks, it might have been Mafia controlled, but guess what? It was the only place that was safe for us.”

When he stepped through the doors of the Stonewall Inn that night, he could never have known what would unfold. At just 18 years old, Mark found himself embroiled in the Stonewall riots. The events of that night are widely remembered today for birthing the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement.

Mark still remembers the moment. What was supposed to be a fun night out turned into something more sinister.

“That night, the lights blinked on and off,” Mark explains. “I didn’t know what that was about. I asked the person next to me: ‘What’s happening?’

“They said very casually: ‘Oh, it’s a raid – the police come in, take money out of the cash register, and walk out.'”

The Stonewall Inn’s regular patrons were well used to raids, but what happened that night was a little different.

“Rather than just coming in casually taking money out of the cash register, they burst and broke the front doors down, started breaking up the bar, started smashing bottles of liquor, smashing the jukebox, taking people and throwing them against the wall, using every profanity you could possibly imagine,” Mark recalls.

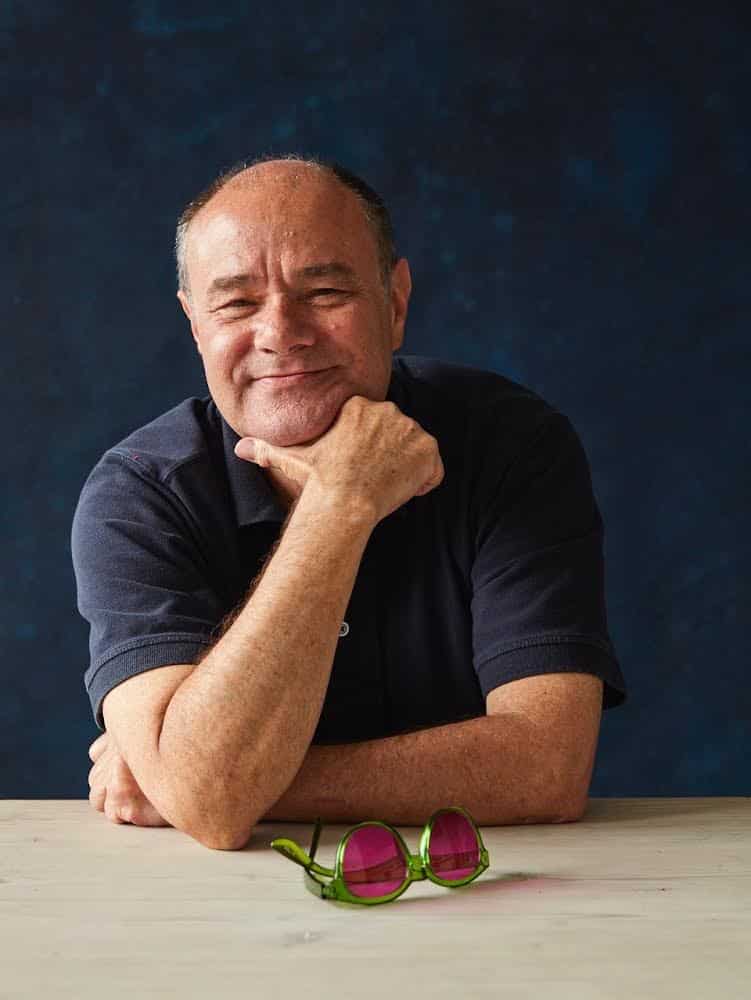

Mark Segal posing in a publicity shot. (Provided)

Once the police got tired of smashing the bar to pieces and harassing its patrons, they started letting people out one by one.

“Looking like the boy next door in those days, I was one of the first to be let out,” Mark says. “I went across the street and just watched – I was fascinated at that point.”

That was when things kicked up a gear. The queer people who had just been thrown out of the bar lined the streets, and when the police opened the door to leave, people took “whatever they had” and threw it at the door.

There were no bricks at Stonewall. Anyone who says that wasn’t there

Contrary to popular opinion, no bricks were thrown.

“It could have been pennies or pence from their pockets, it could have been a can on the street – that’s what it was. There was no brick at Stonewall. Anyone who says that wasn’t there. It was just light stuff being thrown at the door.”

Gradually, the crowd worked up to throwing stones and hurling insults at the police. Marty Robinson, who became a prominent activist, handed Mark a piece of chalk and told him to walk up and down the street writing messages on the walls urging people to congregate the following night outside the Stonewall Inn.

The Stonewall Inn today. (Getty)

“The second night of Stonewall, Marty and [lesbian activist] Martha Shelley spoke from the very steps of the Stonewall Inn,” Mark says.

“That was illegal. We were congregating – homosexuals were congregating! And we basically dared the police to stop us. Second night, third night, fourth night, we were handing out leaflets on the streets.”

The false mythology around Stonewall isn’t only exclusionary, it’s offensive too

History is always contested – it’s never easy to settle on a single version of the past because so often we have conflicting accounts and different perspectives to contend with. Mark is keenly aware of that, but he has little time for many of the myths that have circulated about the Stonewall riots in recent years.

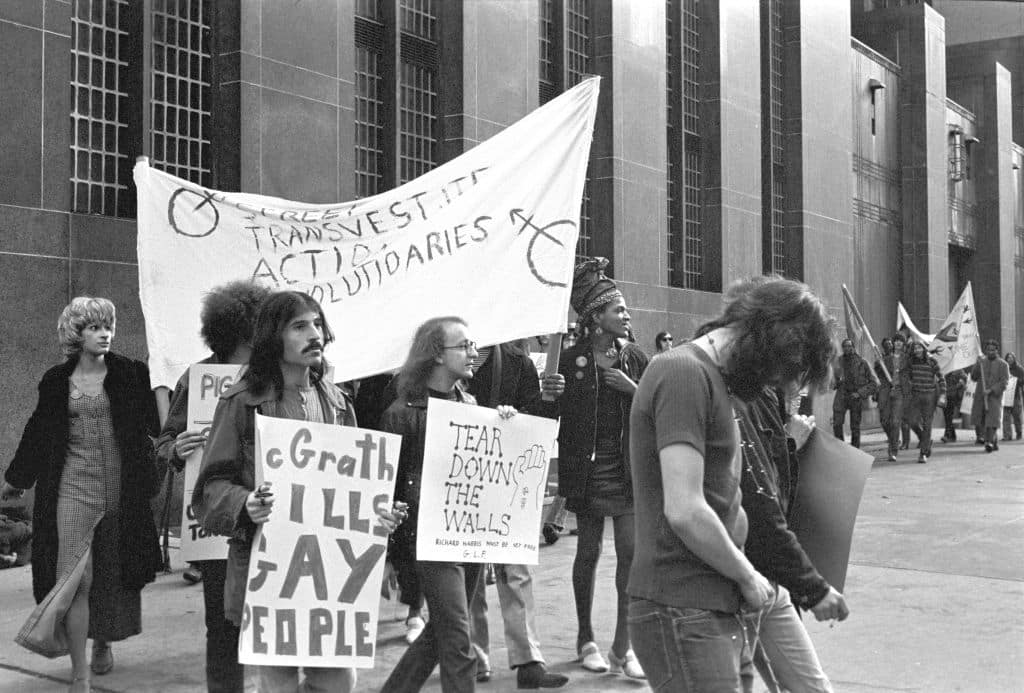

He’s particularly concerned by a small group of people with a particular agenda who have tried to erase the trans community from the Stonewall riots, despite the fact Marsha P Johnson and Sylvia Rivera were heavily involved. Both went on to set up Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR).

As Mark explains, those who took part in the Stonewall riots were seen as the lowest of the low in society. They had “nothing to lose”, which is why they stayed to throw stones, coins and insults at the police. Those with families and good jobs fled the scene, while many trans people stayed behind.

“They had absolutely nothing. Of course they were there,” Mark says.

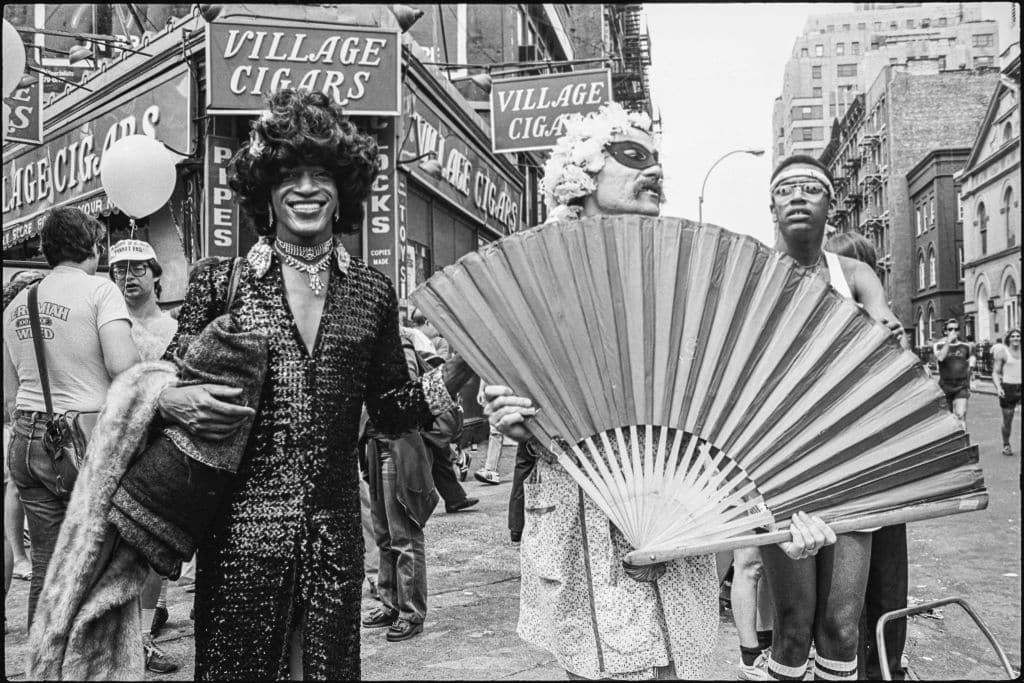

Two people carry the banner “Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries” with the group’s founders Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P Johnson. (Bob Parent/Getty)

Another myth that still boils Mark’s blood more than 50 years on, is the idea the Stonewall riots happened because of Judy Garland’s death. Some have suggested the queer people who were in the bar that night were so devastated by the icon’s passing they revolted when the police smashed through the doors.

“I’m gonna say something I haven’t said before,” Mark explains. “The reason [that myth] frustrates me so much is because people use the story of Judy Garland to belittle us to these show business, silly little queens. We weren’t silly little queens.”

He continues: “I was 18. The majority of people who were [there were] my age up to their late ’20s – Judy Garland didn’t mean anything to us. When I remember dancing in Stonewall I remember ‘Aquarius (Let The Sunshine In)’ by The Fifth Dimension. I don’t remember Judy Garland. That’s silly. It belittles me and everybody who participated.”

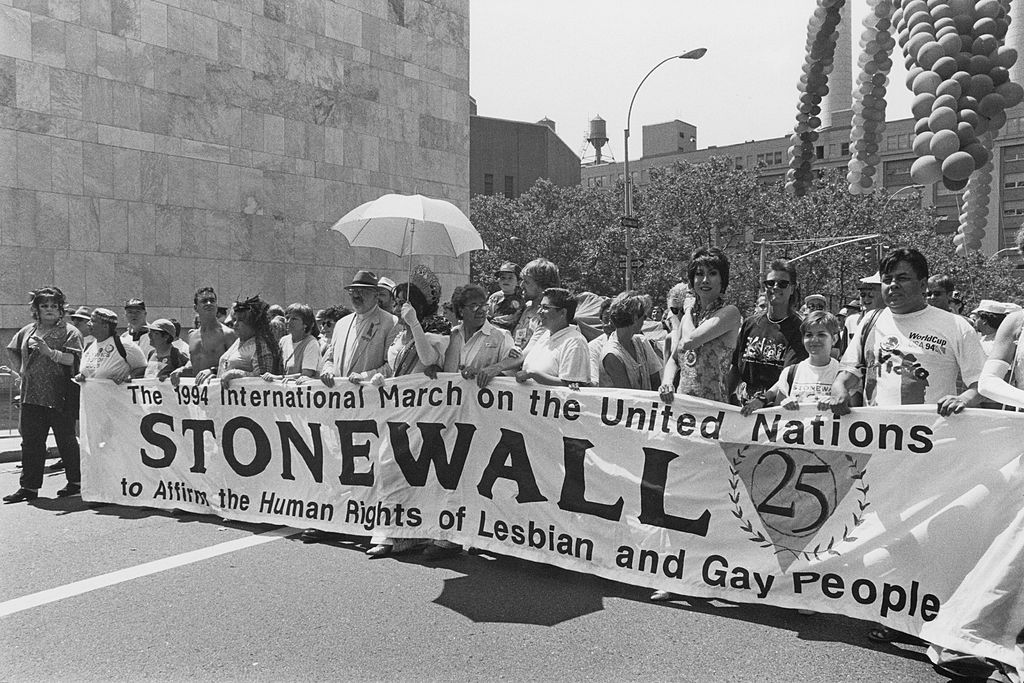

A march to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, New York City, USA, 26 June, 1994. (Barbara Alper/Getty)

Mark points out the Stonewall riots were a “serious event” – he says those who took part should be revered and respected.

“We were fighting against oppression, we were fighting against being belittled, we were fighting against people who would smash us against the wall, who could smash up one of the few places we had [to be ourselves]. Who’s thinking of ‘Over the Rainbow’? It’s stupid and not logical.”

Mark Segal is confused by backslide on trans inclusion

Within weeks of the Stonewall riots, the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) had been formed, and for the first time, queer people across the spectrum were part of a unified movement. He’s amazed today by some of the anti-trans debates he hears from those within the LGBTQ+ community because the GLF settled many of those debates more than 50 years ago.

“At the first meeting of the Gay Liberation Front, that’s when we began to change the world,” Mark says.

“We were all different,” he says. “We were going to be the first diversified, inclusive organisation, and we were going to let each of our members identify how they wished… You want to be a drag queen? Fine. You want to be called ‘her’? Fine. I can’t believe people are fighting over pronouns today when we were accepting of it in 1969 – it seems ridiculous.”

Still, that’s not to say that the GLF didn’t have its issues. Looking back, Mark says it was “dysfunctional” at its core – but that wasn’t necessarily a bad thing.

Marsha P Johnson (centre left, in dark outfit), along with unidentified others, on the corner of Christopher Street during the New York Pride March in 1982. (Barbara Alper/Getty)

“If you wanted to pass something in the group it had to be by consensus, so the meeting went on forever. We were debating everything you could possibly debate because we were trying to figure out who we were,” he says.

“We had lots of differences, but we knew we were under attack and we united. On one side of the room you had fairies, on the other side of the room you had lesbian separatists, but we came together for that year because we were under attack and we knew we had to build something, and we knew if we weren’t united we couldn’t do that.”

Five decades later, so much has changed for LGBTQ+ people – but there are so many battles yet to be won. We might have equal marriage, but trans people are being routinely demonised in the press and by politicians.

Looking back, Mark says much of that early movement was about making gay men and lesbians visible. Now, he says, it’s time to make trans people visible so society can get to know them.

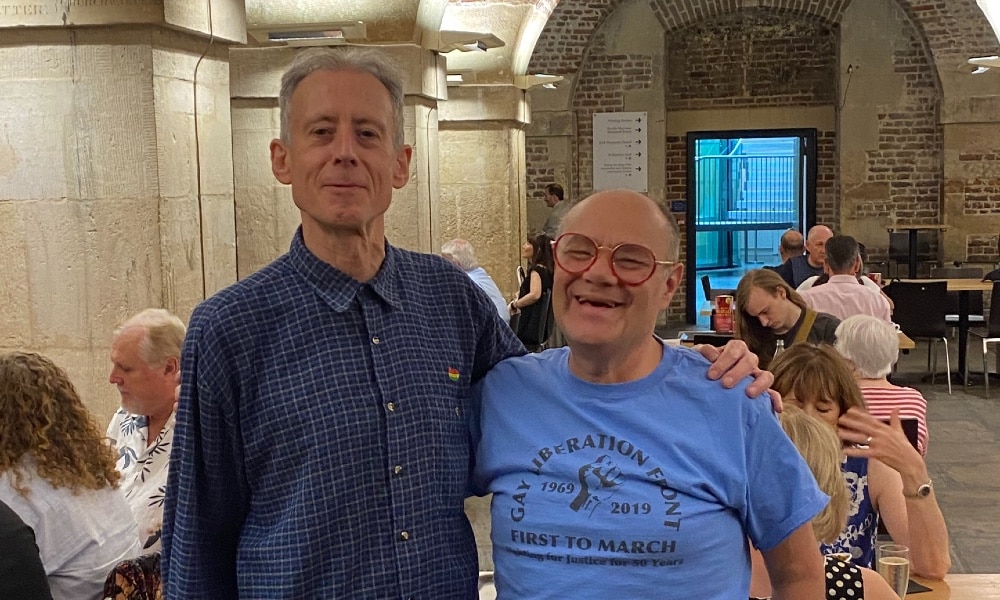

Mark Segal (R) meeting English LGBTQ+ rights activist Peter Tatchell for the first time. (Provided)

“I think it behooves us, who are gay and lesbian, to let trans people be a bit on the forefront, so society can get to know them,” Mark says.

“There was a time when gay men and lesbian women were the monsters in the closet – why? Because they didn’t know who we were. They didn’t know what our dreams and aspirations were. They didn’t know that we wanted to contribute to society, that we wanted to be partners with them.

“They now think trans people are those green monsters in the closet, so we need to do everything we can to support them and show who they are – so society won’t be afraid of them any longer.

“Visibility brings discussion, discussion brings education, education brings equality.”