Stonewall Riots vet on respecting term ‘queer’ and why LGBTQ+ people must talk to their ‘enemies’

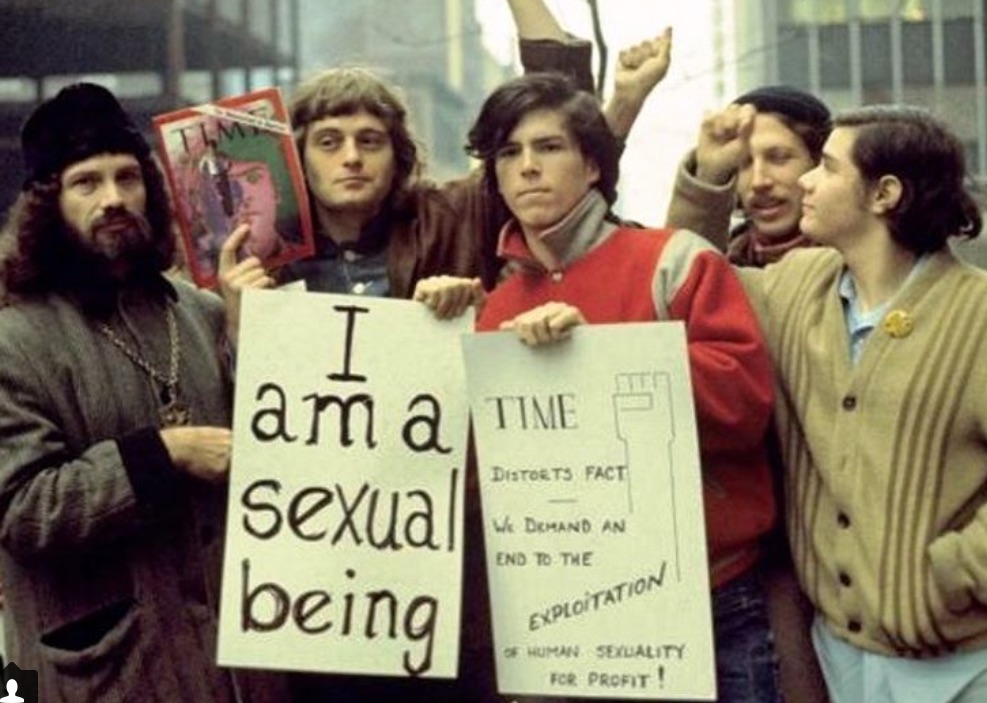

Mark Segal was just 18 when he participated in the Stonewall Riots in June 1969. (Abi Amosu/Supplied)

Mark Segal had been living in New York City as a wide-eyed 18-year-old for just six weeks when he decided to head to the Stonewall Inn on that infamous night of 28 June, 1969.

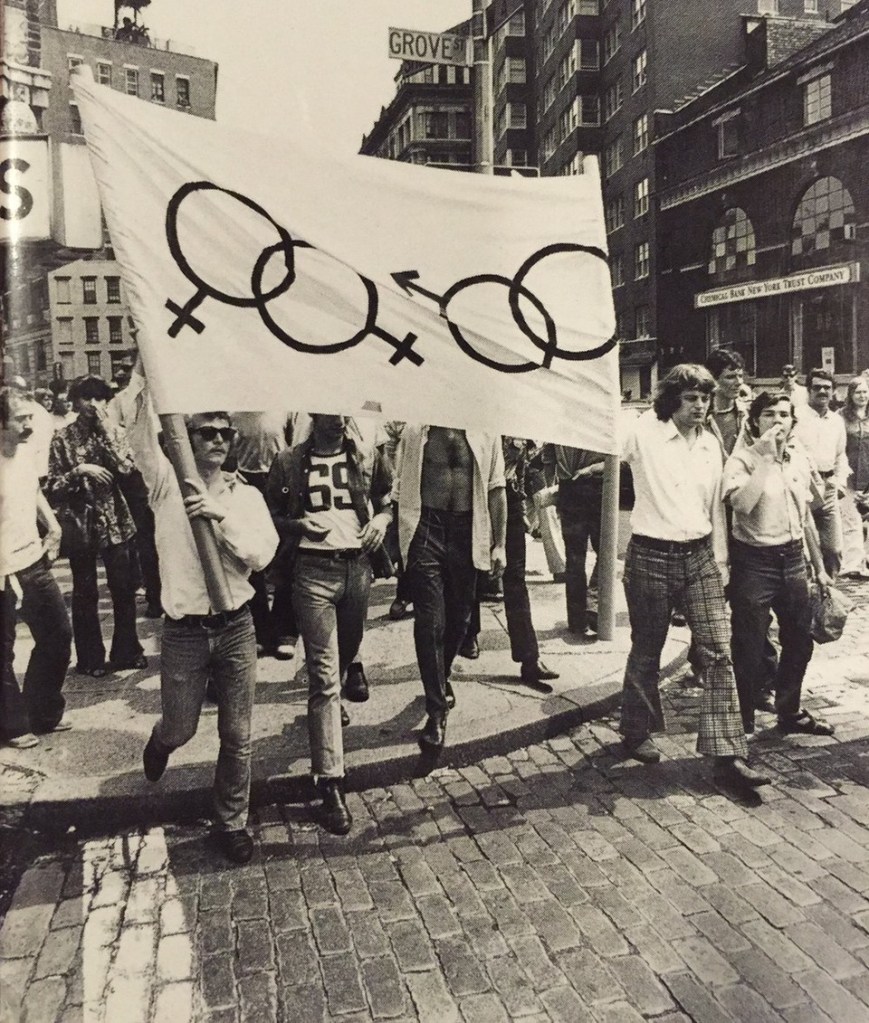

What unfolded that night and over the following days sparked not just the birth of the modern gay rights movement, but a lifelong career in activism for Mark, one of the founders of the Gay Liberation Front and author of 2015’s And Then I Danced: Traveling the Road to LGBT Equality.

PinkNews caught up with the Stonewall veteran, now 72, at a special event hosted by JPMorgan Chase & Co and Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner Law (BCLP) in London on Thursday (23 February), where the journalist and campaigner was speaking on a panel exploring LGBTQ+ stories in LGBT History Month.

The evening saw Mark reflect on his own involvement in the Stonewall Riots alongside other key figures whose work is uncovering the queer community’s rich vein of hidden stories, including Stonewall National Monument Visitor Center (SNMVC) founder Diana Rodriguez, director and co-founder of the Queer Britain museum, Joseph Galliano-Doig, and Patrick Sammon and Bennett Singer, co-directors of the award-winning documentary Cured.

“That’s a grand room in there – I’m usually thrown out of rooms like that!” Mark joked to PinkNews ahead of the panel. “We used to demonstrate in rooms like that, because corporations wouldn’t open their doors to us. Today, they are.

“Why are they doing so? It’s because of all that work that everybody’s done for the last 53 years.”

As someone who’s been at the forefront of that work for the majority of his life, Mark has a unique perspective on the challenges currently facing LGBTQ+ people at a time when division appears to be entrenched in both politics and activism. Here, the heroic community figure gives his take on the mythology around Stonewall, the evolution of queer terminology, and why, in an era of increasing hostility, LGBTQ+ people must remember to “talk to our enemies as well as our friends”.

PinkNews: Did you ever envision during [the Stonewall Riots] that you’d still be talking about those days more than half a century later? Could you feel the weight of history in those moments?

Mark Segal: Every time I get asked that question, I have to think for a little while. And the first thing I would say is, obviously we didn’t know it was going to be history – nobody did! It was spontaneous. I didn’t understand the repercussions of it. People think Stonewall was one night, a flash, and that was it: From the actions of Stonewall came the Gay Liberation Front, from the Gay Liberation front came everything we built, which is the community we have today. So, did I think that was going to be the spark that changed the world? No, I had no idea. None of us did. I didn’t begin to believe it was history until we got together 25 years later and celebrated Stonewall 25.

I’m proud of my history, I’m going to talk about my history. It might not be the mythology that we have out there today, but it’s mine.

What is some of that [Stonewall] mythology that doesn’t marry with your own experience?

Who threw the first brick is one of the biggies. There were no bricks! There were things being thrown, that’s what got the police to react when we were outside, but what were they? They were coins in our pockets, maybe empty cans on the street, a stone. Who threw the first object? Nobody really knows. Again, it was spontaneous. It was a crowd scene. It was a riot! Do you know what happens during a riot? People are running everywhere, people screaming. It’s not as though you’re really looking at one thing. From Stonewall to the first Pride, that’s the first magic year – that one year where we did create a gay community.

You’ve spoken about how the Gay Liberation Front was a real unified community, with all different facets coming together. Looking at the modern day and the political situations in the US and UK, particularly regarding trans rights, do you worry that some of that unity has been lost?

Oh absolutely. What [people] have to realise is how how fractured a community we were before Stonewall, and then how we united. Right after Stonewall we all got together and created Gay Liberation Front – all of us, from all these elements of our community who didn’t like each other! That’s called unity, and that’s the way we created that first magical year, was to work together. Some of the magical things we did for the first time is, you told me what your sexual identity was and it was accepted. You were a he, you were a her, you were – we didn’t use the word trans in those days – a drag queen; whatever that identity was, you were accepted. Gay Liberation Front was the first organisation that accepted self-identity and also was inclusive. We had men, women, people who today [would be] non-binary, people who were trans, Black, white, Latino, there was everybody.

Today, unfortunately, you find each of those segments sort of separating themselves and saying the rest of the people are doing violence against them or offending them. One of the things that gets me angry – everybody wants to be a victim. I’m not a victim. I was never a victim. I wasn’t a victim at Stonewall, I’m not a victim now. If you’re a victim, you don’t fight back – and we have to learn to fight back and to do so with unity.

There are many gay and lesbian people of a certain older generation that take real issue with themes of gender identity, the reclamation of the word ‘queer’, and saying that undermines their own identities and the things they fought for. As someone from a similar generation, what’s your take on that?

So terminology was extremely important to us, which has to do with sexual identity and who we were. The one thing in terms of terminology that I wanted to get away from more than anything else [was], if you want to call me the worst thing in the world, call me a ‘homosexual’. I think that’s the dirtiest word in the world. The second ugliest word at that time to me was ‘queer’. I see people take you at that word today. Now again, I’m from Gay Liberation Front, we say whatever you want to accept as your sexuality or term for you, I’ll respect. And I respect it – just don’t call me that. If you want to be labelled that, that’s fine, I take no offence at that, not at all. You have a right to do that.

We’ve recently been covering the likes of [US Republicans] Ron DeSantis and Marjorie Taylor Geene. There’s so much division and polarisation in American politics that’s become entrenched. There are real people and communities that are on the sharp end of this rhetoric – is finding common ground even possible for queer communities today?

Yes. I can give you an example. I’ve never talked about this before. When Donald Trump was in the White House, one of my friends worked for him inside the White House. I was going to DC, Washington for some kind of event and I said, ‘Hey Jim, I’m coming to DC, do you want to get together for lunch or something?’ And he said, ‘Oh yeah, why don’t you come to the White House for lunch?’ And I said, ‘Sorry, with your boss, I won’t step into the White House, but why don’t we go across the street and we’ll have lunch.’ And we were able to have a dialogue and talk and debate the differences with respect.

Here’s a guy who’s working for Trump, who supports the LGBT community, so he’s a voice inside there – it’s not going anywhere and he will tell you today, it didn’t go anywhere. The point being is he remained an LGBT advocate and then what he does today, which I can’t go on about, he’s able to push for LGBT rights in so many different ways in the corporate world, in the government world. He’s a natural Republican, but he supports the LGBT community. We need to be able to talk to our enemies as well as our friends. If you’re only going to talk to just your friends, you’re not going to do what we set out to do in 1969, which is educate the world so they would eventually not just tolerate us but take us in an make us part of their family – because we are part of their family, whether they like it or not.

What would your advice be to younger people who might be looking at the state of the world today and feeling quite helpless in terms off their ability to change things around them?

I think the most important thing that we can do today – that we said in 1969 – is come out. If you can come out to your parents, to your co-workers, to your family, you’ve already done the most important thing you can do. Don’t argue with them, talk with them. They may not like you at first, but continue the conversation. It’s the most important thing you can do. And by the way, that’s revolutionary.

There’s an old line we used back then which is still true today: if every single LGBT person would come out to their mothers their fathers, uncles, aunts, their cousins, there would be no need for an equality movement, because everybody knows somebody who is LGBT – they just might not know they know somebody who’s LGBT. And it’s also not our right to push people out of the closet.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.