How a lesbian couple’s contribution to Ireland’s Easter Rising was scrubbed from history

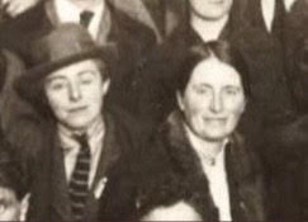

Kathleen Lynn and Madeleine ffrench-Mullen were involved in the Easter Rising in 1916. (Mary McAuliffe)

The Easter Rising was one of the most significant moments in the Irish revolution – but for too long, the role women played has been overlooked.

Of around 2,500 Irish rebels, about 300 were women. Among their ranks were radical, left-wing activists who fought tirelessly to make their society a better, more just place for everybody.

Few worked as hard to make Ireland a better place than Kathleen Lynn and Madeleine ffrench-Mullen. Both women played influential roles in the 1916 Rising, which historians have argued ultimately helped pave the way for the foundation of the Irish Free State in 1922.

For decades, historians viewed Lynn and ffrench-Mullen as friends, but in recent years, their relationship has been reassessed through a queer lens. Not only did they live together, they shared their values and their lives with each other, with diary entries pointing to a relationship of depth and security.

Lynn and ffrench-Mullen moved in together in 1915 and they remained at their residence in Rathmines, Dublin, until ffrench-Mullen’s death in 1944.

Both women found their way into the fight for independence through feminism. They were committed suffragettes who believed in the mission of James Connolly, an Irish socialist who was eventually executed by British forces for his role in the Easter Rising.

Lynn and ffrench-Mullen went on to join the Irish Citizen Army, which led to them taking active roles in the Easter Rising in 1916. Lynn served as chief medical officer in the uprising, while ffrench-Mullen took on the role of lieutenant.

After the Irish revolutionaries surrendered, Lynn and ffrench-Mullen were taken to Kilmainham Gaol where they shared a cell with Helena Molony, another prominent Irish republican.

Mary McAuliffe, director of Gender Studies at UCD, says Lynn’s own writings paint a picture of a couple who were deeply committed to each other from the early years of the Irish revolution right up until ffrench-Mullen’s death.

In one passage, Lynn wrote of her joy at being reunited with ffrench-Mullen in Kilmainham Gaol. When she was moved to Mountjoy prison, she wrote that she would have given £10,000 to be back in Kilmainham with Madeleine.

“That separation really impacted on them,” McAuliffe says.

Once Lynn got out of prison, the women “resumed their life together”, McAuliffe says. They continued their fight for women’s suffrage, for Irish independence, and for better medical and living standards for Dublin’s most vulnerable people.

They were able to exist as a couple “in plain sight” because, at that time, it was common for unmarried women to live together.

“Their inner core friends understood their relationship was not just that of friends. It was something else, but it wasn’t named as such. It was just accepted that this is who they were,” McAuliffe explains.

For years, there was “some resistance” among biographers to write about Lynn and ffrench-Mullen as a couple – but Lynn’s diary entries have made it impossible for experts to ignore the obvious.

“Madeleine is at the centre of her diaries,” McAuliffe says. “Madeleine is there every single day – they’re working together, they’re going on holidays together, she’s worried about Madeleine’s health. She’s very proud of Madeleine in her fundraising activities for St Ultan’s Hospital (a hospital they set up together). They go off to the states together to visit hospitals and understand the best standards and practices that they can bring back to Dublin.

“They have arguments and she gives out about her a little bit as well – that she’s doing too much, that she’s tired. They love going up to their cottage in Glenmalure (in County Wicklow). They have a life together that you just recognise as a couple. That is what they are.”

The evidence doesn’t stop there – there are also diary entries from Irish writer and political activist Rosamund Jacob where she writes about them as a couple.

“Jacob, in her diaries, talks about Kathleen and Madeleine having no use at all for men in the context of a discussion about sex with Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington,” she says.

“You get the sense that there is an acceptance – that their cohort of friends and fellow activists knew they were a couple, accepted they were a couple.”

Kathleen Lynn and Madeleine ffrench-Mullen were committed anti-fascists

Lynn and ffrench-Mullen’s relationship was founded on a deep personal bond, but it was strengthened by their shared values. Both women cared deeply about equality, feminism and independence.

“Both of them were very anti-fascist and loathed the rise of fascism in Europe and were quite taken by communism,” McAuliffe says.

“They were very radical in their ideas. They brought Maria Montessori to Ireland for example and set up the first Montessori unit in their hospital in St Ultan’s. They introduced new types of treatment, better treatments for children. They began inoculation against TB with the BCG vaccine in the 1930s in St Ultan’s and it was one of the first hospitals that did that.”

Both women were also united by their opposition to the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the document that granted independence to 26 of the 32 counties on the island of Ireland. Like many others, they felt that the independence they had won was only a partial victory, with Northern Ireland remaining part of the United Kingdom.

Lynn subsequently ran as a Sinn Féin candidate and was elected to Ireland’s parliament, but she refused to take her seat alongside her party colleagues because of their anti-treaty stance. She lost her seat in 1927.

Both women remained committed political activists throughout their lives, and their relationship remained as steady as ever throughout that time. On 26 May 1944, their years together came to an end when ffrench-Mullen died.

In her diaries, Lynn detailed how she sat beside her partner’s body in the home they had shared for decades in what McAuliffe describes as a “heartbreaking but beautiful passage”.

“She writes about bringing in flowers from the garden – they were avid gardeners so they were always talking about buying bulbs and putting in flowers – so she brings in flowers and sits with Madeleine.”

Lynn lived for another 11 years, eventually dying at the age of 81 in 1955. For too long, her contribution to the Irish revolution – and indeed, her relationship with the woman she shared a life with – was largely scrubbed from history.

Finally, that’s starting to change.

“I believe firmly as a gender historian that you’re only getting half the story, and indeed a skewed version of the story, if you tell it without women,” McAuliffe says.

“When you reinsert women back into those histories, it transforms the story – it transforms the history because you see a broader, more complex history going on.

“An awful lot of the women who were involved in 1916 weren’t just fighting for Irish women, they were fighting for what Constance Markievicz called the three great causes: the cause of Ireland, the cause of labour and the cause of women. They had very well developed ideologies, in some cases much more so than the men, and many of them are much more radical than the men, so when you put them back into the story it changes much of what the story is and complicates it.”

It’s also vital that Lynn and ffrench-Mullen’s queerness is brought to the fore, McAuliffe says.

“We need to write those stories back in and ensure that those histories are told for ourselves, but also for the next generations.”