Monkeypox expert explains how to stay safe from virus at Pride, from vaccines to condoms

Sensible precautions can help LGBTQ+ people enjoy Pride safely amid the monkeypox outbreak. (Getty/PinkNews)

Monkeypox might be spreading rapidly among gay and bisexual men, but that shouldn’t stop the LGBTQ+ community from coming together and celebrating at Pride.

For so many LGBTQ+ people, Pride is a vital opportunity to come together in the spirit of celebration and protest. For others, it’s a chance to forge new connections with others in their community.

Naturally, the worrying spread of monkeypox among men who have sex with men has led to some feeling nervous about attending Pride festivals – but the message from experts is clear: Pride is a safe space, and there are measures you can take to better protect yourself.

Mateo Prochazka is an infectious disease epidemiologist with the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA). He’s also a gay man, which means he’s intensely aware of how important Pride is.

Queer people often meet new sexual partners at Pride events, which is something to be celebrated, but in the face of monkeypox, there are some things people should be aware of.

Be aware of monkeypox symptoms and have frank conversations with sexual partners

“What we want is for people to be aware that these events around Pride can sometimes present opportunities for sex with new partners where people can be exposed to monkeypox. What we want is to minimise the risk of people developing the infection,” Mateo tells PinkNews.

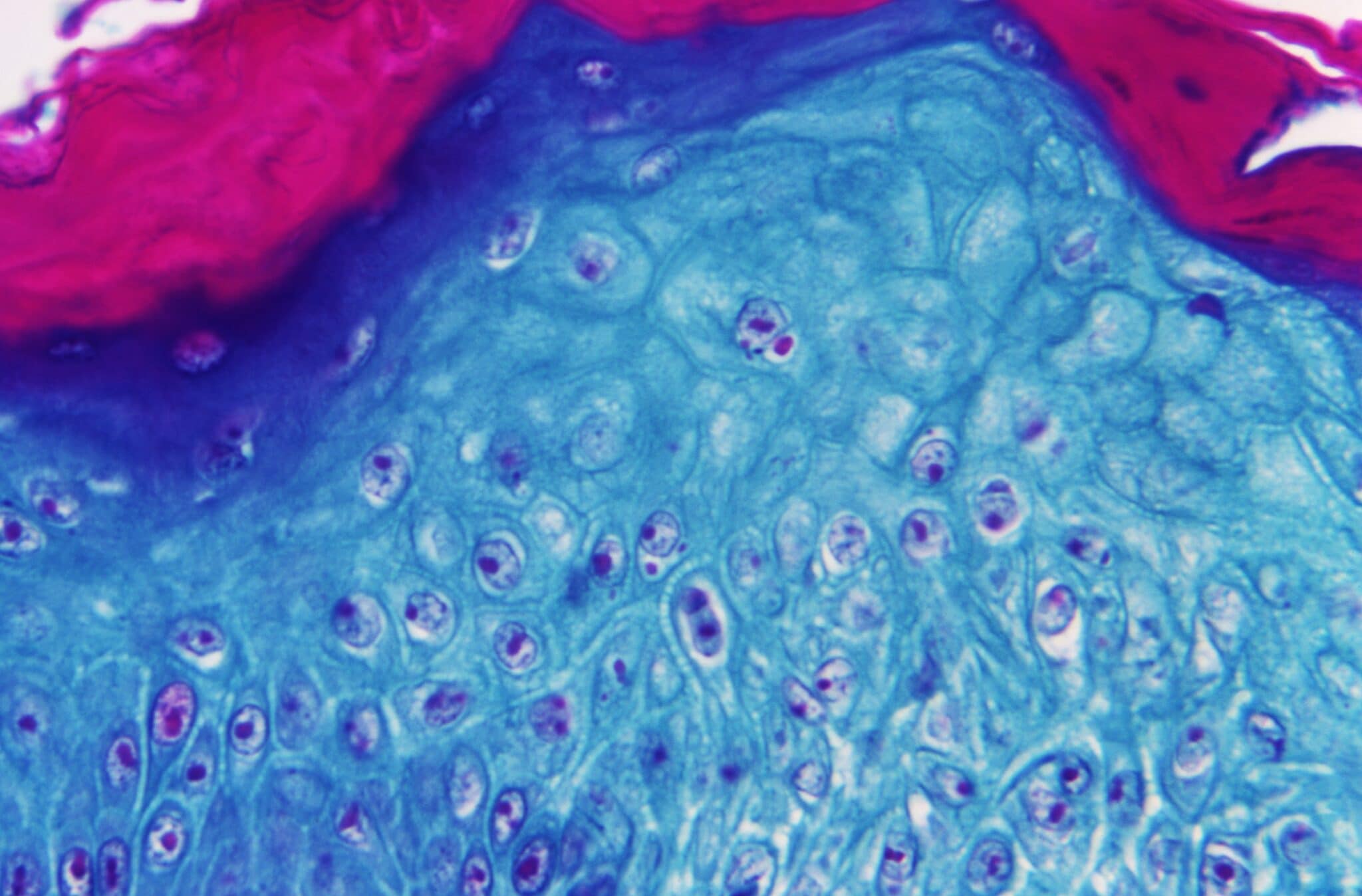

Monkeypox lesions. (MarioGuti/Getty Images)

One of the ways people can minimise risk of monkeypox transmission at Pride is by doing a simple self-check for symptoms before attending. Mateo recommends that people closely examine their skin for any new rashes – many people who have contracted the virus have had lesions on their genitals or around the anus.

“It’s really important for people to know that sometimes the rash can be quite small,” Mateo explains. “Especially because they’re found in the genital, pubic and anal area, sometimes trimming pubic hair can help to spot the skin and make sure there are no lesions. Those kinds of self-checks and self-examinations are really a step forward towards ensuring we don’t have infection.”

Mateo also recommends that people have frank conversations with new sexual partners about symptoms before having sex. Small measures like keeping the light on while having sex can also make it easier to spot lesions or rashes on the skin.

“Of course, people can choose to take a break or decrease the number of new partners and just see a smaller number, or the partners they have sex with more regularly, to minimise risk,” Mateo says. He suggests that people should swap contact details with new sexual partners in case symptoms develop after sex.

There are other measures people can take, but it’s less clear how effective they are right now. Condoms could play a role in reducing transmission, but experts are still looking for concrete evidence to that effect.

“The virus has been isolated from semen and it has been isolated from anal swabs, so we know that potentially it could be transmitted during penetrative sex specifically or during contact with semen,” Mateo says. “But we don’t have strong evidence to support that yet, which is why we’re not calling monkeypox an STI.”

The monkeypox infection has been detected largely among gay and bisexual men. (Smith Collection/Gado/Getty)

Still, because condoms could play a role in protecting people, the UKHSA is currently recommending people use them for 12 weeks after monkeypox infection.

“I do think it’s advisable to wear condoms because other STIs are also in circulation and have been increasing following the relaxation of the lockdowns for COVID-19, so condoms are definitely a good idea, as is HIV PrEP. But specifically for monkeypox, neither of those will necessarily protect you,” Mateo explains.

Abstinence ‘doesn’t work’ and isn’t feasible

Of course, the best way to slow monkeypox transmission would be for gay and bisexual men to lower their number of sexual partners temporarily. Health officials have tended to shy away from blunt messaging like that because it could lead to greater stigma – especially for a community that lived through the AIDS epidemic.

“As a community we have so many lessons learned from HIV and AIDS and from the messages that were given to us,” Mateo says. “I think we know that abstinence as a blanket statement doesn’t work – it’s not feasible or acceptable. But what is true is that small changes in our behaviour can support controlling this outbreak. This can include taking a break if we have symptoms, only having sex with people we know, or maybe minimising or decreasing your number of sexual partners.”

Mateo also suggests that people in open relationships may want to close them temporarily, but he stresses that each person must make their own decisions about what’s right for them.

“Some people are keen to continue engaging in these behaviours even when they are equipped with this information, and that will be their choice,” he says.

Pride revellers holding a giant flag with the rainbow colours. (Tristan Fewings/Getty)

Meanwhile, LGBTQ+ people who are going to Pride festivals but aren’t planning on having sex with new partners shouldn’t be worried.

“From interviewing hundreds of cases we know that people are acquiring the infection mostly through sexual contact, not necessarily through social events, so I don’t think people should be afraid or concerned about going to dance parties or to events where you may be in the same space as other people. It’s usually direct and close contact, such as the kind of contact you have during sex that facilitates transmission of infection.”

Those who are at a higher risk of contracting monkeypox – specifically those who are having sex with new partners or with multiple people – should try to get a vaccine as soon as possible. Smallpox vaccines are being used to combat the spread of the virus.

We definitely want people to get vaccinated, especially if they anticipate that during Pride events and festivals they will be engaging in sex with new partners.

“After two doses of vaccine, almost all people develop antibodies and should therefore have a good level of protection against monkeypox,” Mateo says. “It is less clear what level of protection you get from a single dose. One dose of MVA vaccine is offered to help modify or reduce the symptoms of disease and should also help to kick-start your protection for the future. No vaccine is 100 per cent effective, so after vaccination you should continue to be aware of the risks and symptoms of monkeypox.”

Mateo adds: “We definitely want people to get vaccinated, especially if they anticipate that during Pride events and festivals they will be engaging in sex with new partners or participating in group sex. If you think this is your case definitely come forward and get your vaccine.”

LGBTQ+ people can still have fun, but should be aware of monkeypox risks

Monkeypox has led to increased nervousness and fear in the LGBTQ+ community, but Mateo’s message is clear – it’s still possible to have fun, to celebrate, and to join in the spirit of protest while staying safe.

“As a community I don’t think we should let fear of infection or stigma to prohibit us from having a joyful Pride, but it also needs to be a safe Pride in order to take care of our health,” he says. “I think it’s perfectly fine to go and celebrate but it’s good to do it being aware of the risks.”

It’s really an unpleasant infection, it can be quite painful, it can lead to very nasty experiences and to a lot of self-stigma and shame as well.

He adds: “As a government official, I cannot tell people, ‘Change your behaviour.’ But as a member of the community, and as someone who has so many friends who feel at risk, the message I want to convey is people should be taking care of themselves. It’s really an unpleasant infection, it can be quite painful, it can lead to very nasty experiences and to a lot of self-stigma and shame as well.

“I think it’s really important that we consider these things and maybe think about small changes in our behaviour that can decrease risk as we are getting vaccinated.”