New national HIV archive brings together 100 ‘powerful and extraordinary’ stories of epidemic

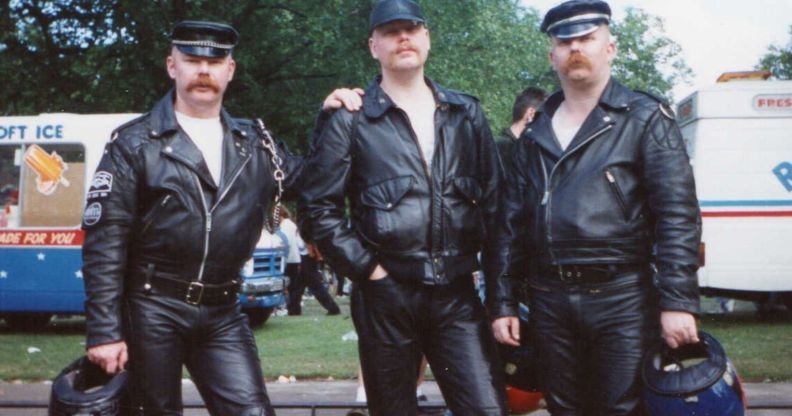

Stuart Conroy (died 20 August 1992), Tomas Jerkestad (died spring 1994), and Steve Craftman, who is still alive today, pictured at a Pride event in 1989. (Supplied)

As the gap between the height of the HIV and AIDS epidemic and the present day widens, so it becomes more possible that people will forget just how deadly the virus was.

That’s why producer and director Paul Coleman has brought together 150 hours of filmed testimony for the National HIV Story Archive. It’s a powerful collection of interviews that gives an unflinching personal perspective of what the epidemic was like from those at the centre of it.

Paul came up with the idea because of his own experience. Like so many others, he lost a friend to HIV/AIDS in the early 2000s.

“I was thinking about [my friend] and the fantastic times we’d had together, and I wanted to take a trip down memory lane,” Paul says.

“I suddenly had this terrible realisation that all the people who I knew who knew [my friend] were also dead. It made me feel really sad, but it also made me [wonder] how many other people have no way of expressing their memories.”

What started out as a film quickly turned into an archival project. As Paul sat down to interview those who had lived through the epidemic, he realised the recordings were something of a historical treasure trove.

“I thought, ‘They’ve got to be safe for ever, they’ve got to be archived’.”

‘Deeply upsetting’

Paul and his collaborators set out to interview 100 people to ensure such stories would never be forgotten.

The National HIV Story Trust came together with no money and just a few volunteers. Word spread gradually, and, before long, they had people coming forward.

“We wanted it to be as natural as possible,” Paul explains. “Rather than us saying it can only be gay men who are HIV-positive, we wanted to see who else would come in, because the story of HIV and AIDS is so much broader than just gay men – it’s all the people around them.”

Conducting the interviews wasn’t easy. Some of the participants hadn’t spoken about their experience in 30 or 40 years, and, naturally, tears often flowed.

“Some of it was incredibly traumatic. To ask people to delve back into that period is quite a big ask, so people thought long and hard about whether they would do that before agreeing to join us.”

Paul describes hearing their stories as a huge privilege, but it was also an emotional rollercoaster that was hard to bear. He had to put in place coping mechanisms to help him get through interviews without bursting into tears.

“It took me back to that time and I hadn’t gone there for so long, for 30-odd years,” Paul explains.

“It was deeply, deeply upsetting at first – I mean crushingly so. Some of the stories are so powerful and so extraordinary that they took my breath away. There are moments in the interviews where you can hear me gasp because I’m so shocked by what someone has said to me, or I’m so taken aback by what someone did to someone else.”

As the epidemic enters its fifth decade, there has been a number of projects memorialising those who lost their lives, and honouring those who survived, including the Channel 4 drama It’s a Sin, and the podcast series We Were Always Here, the interviews for which have also been archived, at Bishopsgate Institute.

Such projects represent a determined effort to make sure the height of the epidemic isn’t forgotten, while it remains in living memory.

“When we started this, people weren’t talking about [AIDS]… it hadn’t been mentioned for a long time and it became very evident to me that people were beginning to forget,” Paul reflects.

“Even worse than that, younger generations didn’t even know about it.”

He adds: “I think everybody can take something away from the story of HIV and AIDS, but ultimately I just don’t want people to forget.”

The National HIV Story Trust video footage is now safely housed at the London Metropolitan Archives, which is owned by the City of London Corporation.

Laurence Ward, head of digital services at the archives, says the project will ensure personal stories will still be available in 100 or 200 years.

“The interviews are humbling to listen to,” Laurence says.

“I think there are lots of really positive things that having the collection here at the London Metropolitan Archives are going to do.

“It’s an incredible thing for us as an archive service to be able to preserve them and make these films available.”

Interviews conducted for the National HIV Story Archive will be publicly available at the London Metropolitan Archives from this month. Read more about the archives here.

How did this story make you feel?