Anna Calvi on David Bowie’s enduring queer legacy and why she’s an unflinching trans ally

Anna Calvi is marking 50 years of David Bowie’s Aladdin Sane with a tribute concert. (Ollie Millington/Redferns/Duffy Archive/The David Bowie Archive)

Musician Anna Calvi was seven when she first heard David Bowie. His 1969 breakout track “Space Oddity” was playing on the car radio, and she was struck by its peculiarity.

The obsession blossomed from there, and she saved her pocket money to buy her first record: Bowie’s stunning sixth album, Aladdin Sane.

Three decades, three albums and three Mercury prize nominations on, and Calvi’s fascination with the Brixton-born singer-songwriter has come full circle.

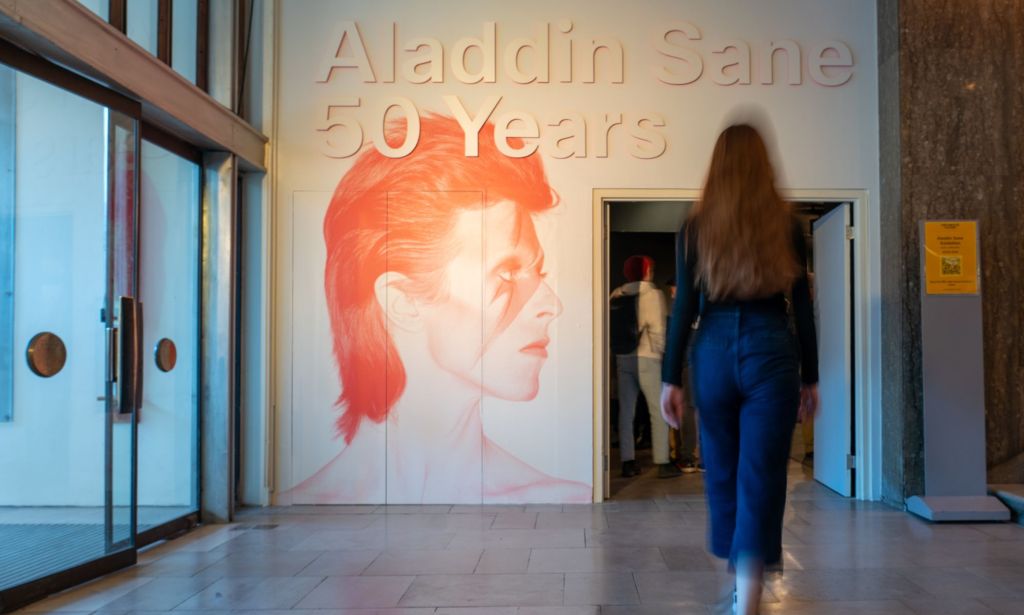

On 21 April, she’ll perform as part of an orchestral tribute concert at London’s Southbank Centre, alongside other queer artists such as Scissor Sisters’ Jake Shears, to celebrate Aladdin Sane‘s 50th anniversary.

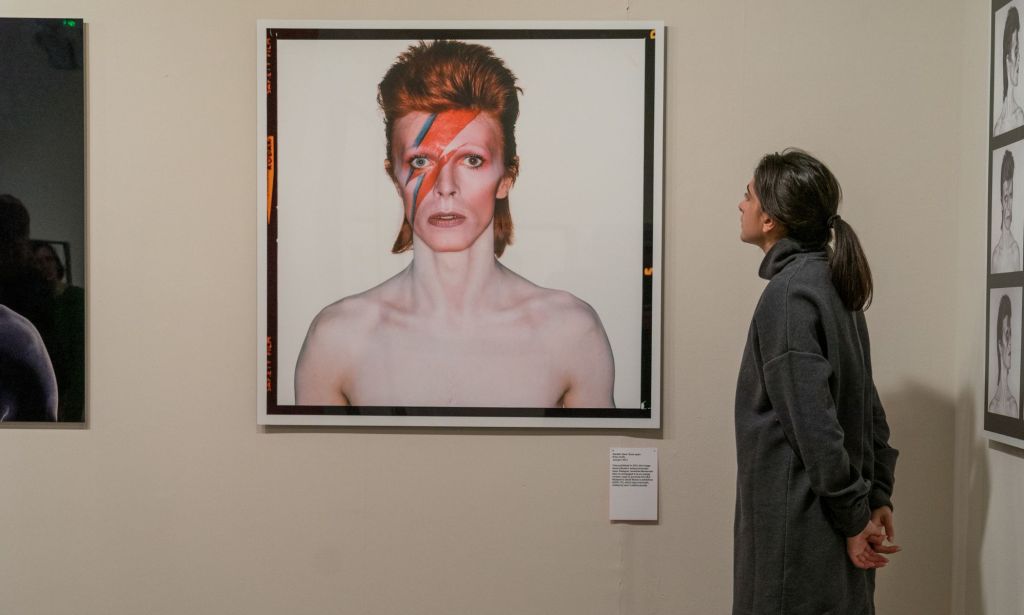

The album’s celestial artwork – featuring Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust with signature red-and-blue lightning bolt, vermilion hair and magenta eye makeup – has embedded itself in queer culture, paving the way for a generation of artists to explore gender expression in their own performance art.

“Even as a little kid, I connected with the queerness of him and the way he was androgynous,” Calvi says of how Bowie has influenced her career and life. “Even though it was way before I understood that part of myself, I feel it was subliminally in there, and I was responding to it.”

Entering the music industry as an out lesbian in the late noughties, Calvi was part of a new generation of artists who were able to be explicit about their sexuality.

This, in no small part, was influenced directly by Bowie’s nonchalant approach to his own identity – throughout this 50-year career, he identified as gay, bisexual, straight and practically everything in between. He refused to let it define his artistry. He played with it, poking fun at those who questioned it.

“I remember seeing an interview with him, and he was saying to this straight interviewer, ‘Well, don’t knock it ‘till you’ve tried it, just, give it a go’,” Calvi says.

“I would love to see supposedly straight men be a bit more fluid and allow themselves to be free in their expression.”

Calvi believes Bowie’s blasé attitude towards sexuality, regardless of how he identified, shunted public perception of queer people, helping to strip away the idea that the LGBTQ+ community “is something kind of perverse”.

She explains: “He gave a lot to the queer community by not stigmatising that part of himself,” adding that the way he subverted gender presentation was a “Trojan horse” that allowed people to express themselves however they see fit.

“It’s a really beautiful message that I think reached a lot of people and actually made a difference to a lot of people’s lives, mine included.”

Queer female musicians were undoubtedly welcomed with wider arms during the period when Calvi’s career took off – artists including Ladyhawke and Brandi Carlile were enjoying mainstream success, while Gossip’s Beth Ditto topped the then-prestigious NME “Cool List” in 2006.

However, not everything was, or is, rosy. Calvi distinctly remembers Ditto being reviled by the tabloids for being a “fat lesbian”, while artists such as Lady Gaga were relentlessly quizzed about their gender and orientation. While she feels there have been giant strides in the past decade – particularly when it comes to artists being seen for their music first, identity second – she believes the industry, and society as a whole, still has a problem. A very male, very cis, very straight problem.

“Heterosexual sexuality is everywhere,” she says. “We live in a society that’s aggressively heterosexual. If you’re anything other than that, it becomes a talking point.”

In terms of the music industry, she decries the lack of space given to women performers on the UK’s biggest music platforms. At this year’s Brit Awards, no women were nominated in the best artist category. When Glastonbury returns this June, no women will headline the pyramid stage.

It’s an issue that irks Calvi no end. “If you look at the canon of popular music, it’s been so dominated by one particular voice, which is the straight white male,” she says. “All of the biggest artists in the world, to me, are women.”

The discussion around gender and gender expression in the music industry is a hot potato. One of the reasons why the Brit Awards failed to nominate any women in the best artist category was because, for the first time, the award was genderless.

Predictably, bigots blamed Sam Smith, who is non-binary, for the Brits’ failure to spotlight any women, despite proof that genderless awards can and do work.

The vitriol against Smith has snowballed as they experimented aesthetically with their queer identity – much like Bowie did, all those years ago.

When talk turns to trans and non-binary rights, Calvi becomes increasingly passionate.

“There’s this massive reaction and kickback from people who are just seemingly absolutely terrified by the idea that gender might be fluid,” she says. “It’s really shocking to see how trans people are being treated.”

It’s sickening, she adds, to see the fight for women’s rights contorted into an anti-trans narrative.

“I saw an article the other day and the [headline] was ‘Gender War’. Of all the f**king wars that are happening in the world right now, you’re choosing to create one called a gender war? Who is that serving?”

If we are truly committed to improving women’s rights, Calvi insists our focus should be elsewhere, such as on “making misogyny a crime” or increasing the pitiful one per cent conviction rate of rapists in the UK, rather than putting trans women under a microscope because they want to use the toilet. “It’s such a fake concern,” she says. “It’s so depressing.”

Perhaps the upcoming anniversary of Aladdin Sane can act as a small reminder that queerness, gender expression and non-conformity have always existed, in art and in life. For her part, Calvi is looking forward to getting on stage to honour the person who shaped her as an LGBTQ+ artist.

“I’m gonna be on stage and I’m gonna have flashbacks of being a 10 year old, watching [Bowie’s] tour video every day before school,” she grins.

“It makes me feel really proud. If I could tell that little girl that one day she’s gonna be doing this, her mind would be blown.”

The Southbank Centre is celebrating 50 years of David Bowie’s Aladdin Sane through exhibitions and events until 28 May. Anna Calvi will perform as part of Aladdin Sane Live on Friday 21 April.