Author Liv Little explains why her novel Rosewater ‘didn’t need a traumatic coming out moment’

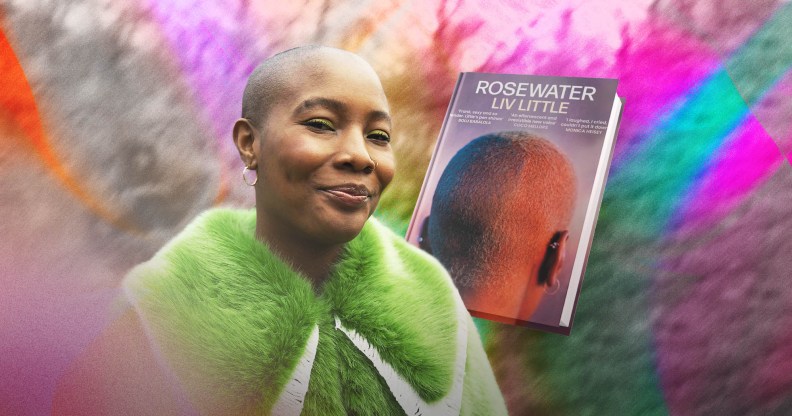

Liv Little on her debut novel Rosewater. (Chantelle Nash/Dialogue Books)

Award-winning journalist Liv Little has spoken to PinkNews about the power of being seen, queer love stories and paying homage to the past in her debut novel, Rosewater.

It’s no exaggeration to say that Rosewater was one of the most highly anticipated books of the year long before it had even hit bookshelves. Announced at the tail end of 2021 as the first book to be snapped up by R&B megastar John Legend’s US imprint, Get Lifted Books, intrigue has steadily been building about Little’s first novel-length fictional endeavour, with early reviews describing it as nothing short of remarkable.

Amid the excitement of releasing her debut into the world, however, Little says there was “a lot going on” behind the scenes. After stepping back as chief executive of gal-dem magazine a year earlier, she put her MA in Black British writing at Goldsmiths, University of London, on hold when her father was diagnosed with motor neurone disease.

Throughout the final stages of Harry’s illness until his death in 2022, she took him “in and out of hospital appointments”. Writing the novel became a source of creative refuge as grief took hold.

“It can’t fix your problems, but I know it was an important space for me to be separate from the quite challenging and difficult things that were going on,” says Little, who remains sceptical about the idea that “writing is healing”.

Nevertheless, she sped through her first draft, writing the first 20,000 words in merely five days. “I had a lot in my head that I needed to get down on paper at that point [in my life]. It was a year of writing, writing, writing.”

Rosewater follows Elsie, a 28-year-old British-Guyanese poet who moves in with her high-school best friend, Juliet, amid the chaos of eviction, unemployment and family drama.

For Little, who is of Guyanese and Jamaican descent, but who grew up in south east London, it was important to explore the forgotten history of queer Black Britain.

“I was really interested in queer Black Britain in the 80s and 90s,” she explains. “What did that look like? What did that feel like? What were some of the important moments and places and spaces?”

Take Maggie, an aunt-like figure who Elsie meets at the local queer bar. After striking up a friendship, the pair begin an email exchange in which Maggie sends her new friend paraphernalia from LGBTQ+ clubs and bars for Black people that she visited in her youth.

The eureka moment that made Little feel truly seen for the first time came in 2016 with the publication of Jamaican author Nicole Dennis-Benn‘s novel Here Comes the Sun, which explores themes of family, dating, colourism and queerness through the inter-generational story of three women from Montego Bay. “It was the first time I felt there was something very close to me in a book, which is really powerful,” she remembers. “Very life-affirming stuff”.

As Little worked to articulate the vibrancy of London’s queer Black community in Rosewater, she found she was able to channel her own feelings of grief through Elsie, who grapples with a profound sense of loss after being evicted.

“I’m definitely not the main character,” she explains, “but I drew a lot of inspiration from the people and places that mean a lot to me.” Case in point: Little’s grandma, who she has previously described as “the sassiest lady” she knows, is the muse behind Elsie’s grandmother, and brings the richness of Guyanese culture to life through her food and colloquialisms.

“She went over all the dialects with me to make sure everything was right,” Little remembers fondly. Elsewhere, Elsie’s ode to her grandmother’s Pepper Pot recipe – one of four beautiful poems by Kai-Isaiah Jamal in the book – brought tears to Little’s eyes.

Rosewater comes at a time when Little is embarking upon a new chapter of her life. Weeks after the shock closure of gal-dem, the online and print magazine she co-founded in 2015 as a means of elevating perspectives of people of colour from marginalised genders, Little remains committed to bringing representation to the publishing world. “I just write the things I want to read,” she says candidly.

“When you are writing from the inside, rather than the outside looking in, it’s easier to be real and tell the story in the way you want.”

In her own stories, representation is approached organically. “I’m interested in unpicking all the layers of what makes people who they are. So, it would be odd for me, someone who hates when things feel like an add-on or super ‘tokenistic’ or unrealistic, to do that myself.”

It’s no spoiler to note here that Rosewater is, in part, a queer love story. As Elsie and Juliet follow the friends-to-lovers pathway, Little exquisitely captures the yearning between two people who keep passing like ships in the night. And despite the uncertainty plaguing Elsie’s life for much of the novel, Little was determined to make her character certain of her sexuality.

“That part of herself she is absolutely certain of and that was really important to me,” the author says. “There didn’t need to be some traumatic coming out moment or story, it’s not about that.”

From one-night stands and situations to soul-mate bonds, Little centres the “intensity” of connections between queer women, something to which she can relate. “In my early twenties, when I made these great friendships with women, I’d have a moment where I would be like: ‘Do I like this person or I am just building this really beautiful friendship?’

“Often it was just the beautiful friendship, with an intensity of love where the lines were always a little bit blurred. My friendships are really deep and enduring, just as important as romantic love.”

Indeed, Rosewater is a novel of multitudes, exploring issues of class, race, LGBTQ+ rights and inter-generational healing. In the book, Juliet works full-time as a primary school teacher with a side hustle as a cam girl, while Elsie is struggling to keep her dreams alive as she searches for job security and a new place.

“Diversity is not just about whether you are Black or white, there are so many other things that come into play,” says Little.

“I had a dad who grew up with debt. I did a lot of research around the legislation, the psychology, the PTSD, the trauma, the anxiety, drawing from my own experiences as well. There are moments in the book where [Elsie] just forgets to breathe and that’s something I did for a long time. I’ve struggled with my mental health, that feeling of panic and terror.”

At its heart, however, Rosewater is a love letter to family and friendship. In one scene, Elsie discovers that her gran also had relationships with women, leading to a poignant moment of bonding.

“Often when you have older characters in books, you run the risk of them becoming teachable characters for the younger generation and I really didn’t want it to be like that,” says Little. “I wanted everyone, regardless of age, to be able to show up as their full selves and live full and dynamic lives.”

As for what readers can take away from the book, Little simply hopes that it “touches people” in some form, no matter how big or small. “Our experiences are not homogenous but there’s a good cast of characters. I hope there is something for people figuring themselves out and trying to navigate this very complicated and messy world that we live in.”

Rosewater, by Liv Little (£14.99, Dialogue Books), is out now.