Meet Barbara Gittings, the Emmeline Pankhurst of LGBT+ rights in the 1960s

Ask yourself, why have you never heard of Barbara Gittings?

Affectionately dubbed the mother of the LGBTQ civil rights movement, Gittings was a pioneer for LGBTQ rights in America during the 1950s – almost two decades before the Stonewall Inn Riots broke out.

Amongst other things, Gittings helped have homosexuality declassified as a mental disorder by the American Psychiatric Association.

She was the editor of the first lesbian magazine, The Ladder, and took the helm of the New York branch of the first lesbian rights group Daughter of Bilitis.

Today, every school child has heard of the figure heads of important equal rights movements, from Martin Luther King to Emmeline Pankhurst.

But Gittings, for all her bravery, ambition and success, has been ignored from the list of our most revered of our historical heroes.

Here’s everything you ought to have been taught about this remarkable lady in school.

Early experiences with the LGBT+ movement

Born into a Catholic household in Austria as the daughter of a U.S diplomat, Gittings was smart, bookish, and attracted to girls from a young age.

When the Second World War broke out, she and her family moved to Wilmington Delaware, where as a teenager Gittings first began to encounter prejudice both at school and at home.

At first, Gittings strove to understand her sexuality through literature.

Her father caught her reading The Well of Loneliness, the 1928 novel of lesbian love by Radclyffe Hall and, finding himself unable to speak to her on about it, wrote her a letter demanding that she burn the book.

Related: Here are all your rights if you are bisexual

Kay “Tobin” Lahusen (left) and her partner Barbara Gittings with stuffed dinosaurs in 1995 (The New York Public Library)

Fortunately, Gittings could not be dissuaded. Years later, when she left home to attend college at Northwestern University in Chicago to study drama, she dug out as much literature surrounding homosexuality as she could.

She discovered that according to the preserving wisdom of the day, she was mentally unwell.

Speaking to the publication American Libraries in 1999, she explained: “I had to find bits and pieces under headings like ‘sexual perversion’ and ‘sexual aberration’ in books about abnormal psychology…

“I kept thinking ‘it’s me they’re writing about, but it doesn’t feel like me at all.’” These were, she said, the “the lies in the libraries.”

Working for Daughters of Bilitis

Gittings dropped out of Northwestern after her freshman year, and began her career as an activist. In 1958 she took over leadership of the New York branch of the Daughters of Bilitis, the first lesbian civil and political rights organisation in the US.

According to Tracy Baim’s biography, Gittings fought hard against the Daughters of Bilitis’ proclaimed goal to “educate” the lesbians so that they could “adjust” to society – she declared instead that it was society, not lesbians, that needed educating.

The DOB was never comfortable with Gittings’ vocalism, militancy and activism. But, where the DOB let her down, she found support from activist Frank Kameny, who joined Gittings in calling for homosexual activism.

The duo called for homosexuals to picket the White House, the Civil Service Commission, the United Nations and the Department of Defence, demanding that the United States Government address their concerns.

Despite having to commute all the way from her home in Philadelphia, and support herself with admin jobs, Gittings also became the editor for the DOB’s newsletter, The Ladder.

By 1964 she decided it was time to tackle the widely held belief that homosexuality was a preventable or treatable mental illness with her powers as a writer.

In an issue of The Ladder, she tore into a report in the 1964 New York Academy of Medicine, writing that it was: “a reminder of the sly, desperate trend to enforce conformity by a ‘sick’ label for anything deviant.”

Gittings’ article is thought to be the first time anyone had put pen to paper and challenged the psychiatric community on their stance on homosexuality.

Related: Here are all your rights if you are a lesbian

Barbara Gittings (left) and Kay “Tobin” Lahusen in 2001 (The New York Public Library)

It took Gittings and Kameny many years before American medics ceased to think of homosexuality as a sickness from which people could be cured.

Even today, anyone with an ear to American politics will know that some groups still believe ‘Conversation Therapy’ can ‘cure’ homosexuality – incredibly, Vice President Mike Pence’s 2000 congressional campaign was widely thought to signal his support for the ‘treatment’.

Nonetheless, thanks in no small part to the activism by Gittings, homosexuality was eventually removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM) by the American Psychiatric Association in the 1970s.

Barbara Gittings’ legacy

David Carter, the author of Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolt credited Gittings with being “one of the rare people in the homophile movement – before Stonewall – who took a militant stance.”

Alongside her achievements in transforming the way homosexuality is understood by society, Gittings helped mould the American Library Assocation’s Gay Task Force.

Today known as the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgendered Round Table, it’s a place where curious minds can find the information and support that Gittings so longed for as a young person herself.

Gittings received plenty of awards, including honorary membership to the American Library Association and the honour of having The Free Library of Philadelphia name its gay and lesbian collection after her.

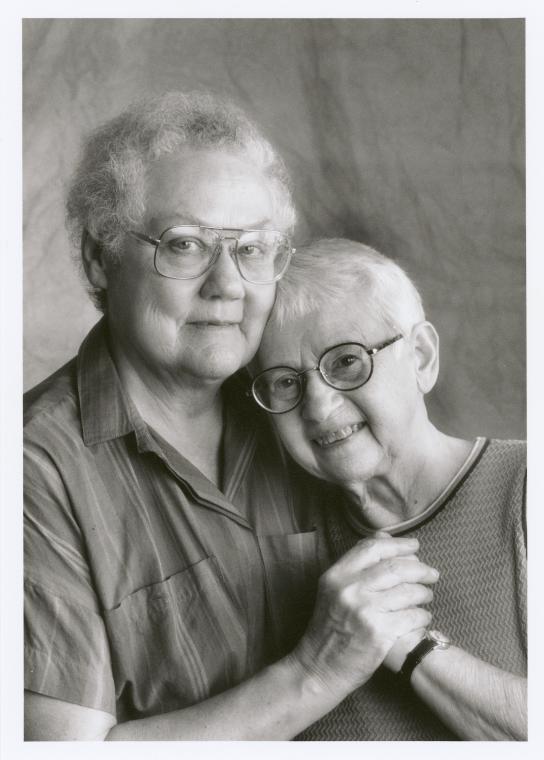

Barbara in later life (Creative Commons)

Related: Here’s all the hottest lesbian porn that requires your attention

In 2012, five years after Gittings died of breast cancer, the City Council of Philadelphia named a block of the city the “Barbara Gittings Way.”

Asked how Gittings would want to be remembered, her partner of 46 years, the lesbian photojournalist Kay Lahusen, said that Gittings “would want to be remembered for the love she leaves behind.

“Love of the cause, the gay community, love of justice, love of music and books, and love for me.” And so she should be.