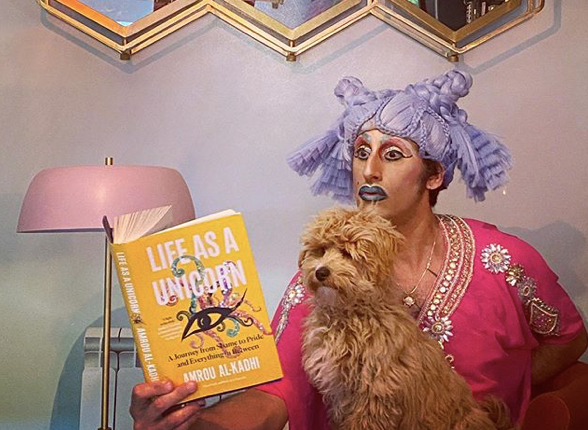

How a marine fish tank helped non-binary drag queen Amrou Al-Kadhi embrace their gender: ‘It seemed so damn woke in the ocean’

Non-binary, Muslim drag queen Amrou Al-Kadhi. (glamrou/Instagram)

Amrou Al-Kadhi, a queer non-binary Iraqi-British drag queen, writer and performer, recalls how a teenage visit to a marine fish store helped them understand their gender.

When there were no after-school clubs for me to stay behind for, I would tell my parents that there were, so I could wander around Barnes and delay going home.

On one such afternoon, when I was thirteen, I stumbled upon a street in Mortlake I’d never ventured down before – and it was here that I encountered the Tropical and Marine shop for the first time.

In the shop window sat an enormous marine fish tank, teeming with colourful coral, free-flowing anemones, gloriously ornamented fish, and constantly undulating starfish. As I gazed at it, I felt something entirely new – a distinct sense of belonging.

Have you ever seen or heard something – a film, a painting, something fleeting out of a car window, a song or a sound – and felt a sudden emotional clarity, as if whatever you’ve just encountered has always been part of you, and in that moment, both parts have finally been reunited? That’s what this felt like.

I was deeply stirred by the way that the marine creatures moved so freely; the way the soft corals and sea invertebrates seemed to exist without physical boundaries, like warrior shape-shifters; the way the fish regally flaunted their colourful costumes.

That’s how I feel on the inside. In my soul, I’m that colourful; my sexuality, my gender – it’s free-moving, like in the tank. Maybe my soul doesn’t have any boundaries?

I had grown very accustomed to boundaries. I had spliced myself into different sections that existed in segregated spaces.

But here was a parallel universe where everything was fluid. I inched closer to the tank and was hypnotised by the way all the creatures interacted with each other. Cleaner shrimp politely mowed the scales of a fish that was half purple, half yellow; the corals, each with their own distinct texture and colour scheme, seemed to flow as one formless mass with the current of the water.

They were united by their diversity, not divided, like I had learnt to become. Out from the sand emerged starfish, along with hermit crabs and snails, hoovering the sand-bed like a harmonious social collective.

I was desperate to dive inside this wormhole with it, for this new world clearly had so much to teach me.

I was dazzled by the so-called sandsifter starfish, and the way its multiple, separate limbs, each with their own sense of character, could come together as one entity; the factions of my identity felt like tectonic plates at constant risk of an earthquake.

An adorable cylinder-shaped fish emerged from under a rock, its golden sheen with emerald spots iridescent under the tank’s UV light, creating an Egyptian-tone shimmer that reminded me of a dress my mother had worn once in Dubai.

And then I met a tube-like structure from which emerged a fan of patterned feathers (a ‘feather duster’); it was entrancing, infinitely complicated, yet utterly simple, millions and millions of molecules coming together to caress the ocean water calmly, its texture as silky as Mama’s hair.

I edged as close as I could to see inside the creature, but my sudden movement caused the feather structure to retreat into its tube.

(Instagram)

I was desperate to dive inside this wormhole with it, for this new world clearly had so much to teach me.

When I got home, my parents remarked that I was unusually calm – in fact, I was in a hypnotic daze. With a wave of possibility rushing inside me, I spent the evening surfing the internet, wanting to delve deeper into the mysteries of aquatic wonder.

I stayed glued to the computer screen, learning of a universe that was untroubled by the strict boundaries that governed human beings on land. In the marine world, gender fluidity and non-conformism are the status quo.

There are sea slugs called nudibranchs that defy sexual categorisation, containing both female and male reproductive organs, giving and receiving in each sexual encounter, with kaleidoscopic patterns to rival those of a resplendent drag queen.

Marine snail sea hares are able to change sex at will; cuttlefish can alter the pigments of their exterior with the sartorial flexibility of Alexander McQueen, and can disguise themselves as the opposite gender as a social tool; while a male seahorse is something of an underwater feminist, sharing the labour of pregnancy by carrying and ‘birthing’ the young.

This was where I needed to be. I mean, it just seemed so damn woke in the ocean.

This was where I needed to be. I mean, it just seemed so damn woke in the ocean.

It was at this moment that I began to realise I wasn’t fully a man. Now that I have the language to express myself, I identify as non-binary.

I like to be referred to with them/they pronouns, which helps me to feel that my gender is as fluid as the uninhibited curves of an oceanic nirvana; when people correctly use my preferred pronouns, it relaxes me, as if I’m being soaked in a lavender bath, making me feel seen as a person free from gender binaries.

But when I was gazing into the limitless ocean world as a teenager, all I knew was that its boundlessness had an affinity with my gender.

I stayed up late that night and thought about my mother, and about how it was her I most closely identified with in the Middle East.

I had so few linguistic, emotional or social tools to comprehend my gender dysphoria back then, but as I learnt of these polymorphous beings whose bodies or colours didn’t restrict them, I felt an aching sense of connection.

(Supplied)

Extracted from Amrou Al-Kadhi’s Life as a Unicorn: A Journey from Shame to Pride and Everything in Between, detailing their sparkling journey from a kid quietly crushing on Macaulay Culkin to a glam performer unafraid to be themself.

The paperback edition of the book is out July 23 and is available to purchase here.