Florida’s LGBT+ teachers share furious, fearful responses to Don’t Say Gay: ‘Let them come for me’

Tampa Pride Parade, 2022. (Getty/ Octavio Jones)

Since Florida’s ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill was signed into law, LGBT+ teachers have been scrambling to figure out what it means for their students, for their classrooms and for their own livelihoods.

The ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill, officially titled the Parental Rights in Education Bill, bans the discussion of LGBT+ topics in classrooms from kindergarten to third grade.

For children from fourth grade onwards, these topics must be “age appropriate” and “developmentally appropriate”, although the bill gives no definitions for these terms.

Three Florida teachers told PinkNews how the bill is all about scoring political points at the expense of queer kids, and discussed their fears about its devastating impact.

Leslie Owen is a non-binary educator who has been teaching in Florida public schools for 16 years. They describe themself as”slightly left” of legendary anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti.

“Currently, I’ve got a rainbow on my shirt, I’m wearing the colours of Ukraine today, you know, I’d like to be a cause célèbre before I die,” they tell PinkNews.

Owen is so incensed by the disingenuous ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill that they intend to disregard it completely.

“I’m not going to change the way I teach at all. And if they want to come after me, then let them do so.”

Members and supporters of the LGBT+ community attend the “Say Gay Anyway” rally in Miami Beach, Florida on 13 March, 2022. (AFP via Getty/ CHANDAN KHANNA)

Owen doesn’t see how lawmakers can maintain any illusion of the bill being about parental rights – in their eyes, it’s just a plot by Florida governor Ron DeSantis, who can barely contain his presidential ambitions.

“He’s using hatred as his presidential mantra,” says Owen, “and this is his way of doing it.”

Owen currently teaches English language arts at a public, alternative high school for children who are unable to remain in their home schools for a variety of reasons, including behaviour, disciplinary or safety concerns.

They’ve always taught in an LGBT-inclusive manner, and have always operated an open-door policy for parents.

“My classrooms always been transparent,” they say. “There’s no issue. Any parent is welcome to come into my classroom anytime they want to… All my lesson plans are online, always have been, ever since that was a capability. Our literature book is online, the standards are online.

“Any parent could go on to the Department of Education website and look at the standards. Look at the curriculum. Look at the literature. Look at the recommended novels. It’s all there. Transparent, there’s nobody hiding anything.”

Ron DeSantis. (SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty/ Paul Hennessy)

Discussing subjects like gender identity and sexual orientation is vital to teach literature to high school kids, Owen believes.

“If I’m going to teach Walt Whitman, I’m going to teach everything about Walt Whitman… The kids love hearing stories about the people that they’re reading. They love hearing about the fact that Herman Melville was madly in love with Nathaniel Hawthorne.”

The kids have been through so much trauma since Trump was elected.

Owen runs a weekly lunch club called Emotional Learning which, they say, is “basically” a Gay Straight Alliance (GSA) in “hiding”.

Having such a close relationship with the queer kids at their schoolmeans Owen has been able to see the impact that ‘Don’t Say Gay’ has had on them, before it has even come into effect.

“Kids who are who are queer are scared,” they say. “This [county] is Trump country… The people here are QAnon supporters and they’re nuts, they’re armed nuts.

“The kids have been through so much trauma since Trump was elected. They’ve been so afraid. There’s been so much bigotry and hate. There’s been so much encouragement of bigotry and hate, in our schools, in our county, in our state, in our country.

“These kids have been traumatised for years now. I mean, this is 2022. This is six years of listening to this constant condemnation, to these lies.”

Owen has seen especially seen the impact of this trauma on trans kids: “They are lightning rod for everybody’s fear and hate, and why? What has one trans person ever done to anybody? I mean, aside from Caitlyn Jenner, I can’t think of anybody.”

The ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill is taking LGBT+ teachers back in time to their own experiences as queer kids in Florida

Cory Bernaert has been an elementary school teacher in Florida for 12 years, and is in his ninth year of teaching kindergarten. He remembers being seven years old, and realising that he was “different”.

“I didn’t know what it was, I didn’t know how to explain it,” he says. “I didn’t know what I was supposed to do with it. But I knew that I was different.

“I knew in high school that I was gay, but because of the community that I lived in, because of my family, I just didn’t know if they would be accepting, I did not come out until I was 25 years old. I’m now 33.”

In his youth, Bernaert lived in fear that he wouldn’t be accepted, and of how people would respond to his truth.

The ‘Say Gay Anyway’ rally in Miami Beach, Florida. (AFP via Getty/ CHANDAN KHANNA)

“That’s not what I want for my children, and these types of bills, they hinder the little first grade me.

“It’s tough. It’s tough to look back at your own history, and then think that it could be repeated for somebody else, because we should be moving forward and not moving backwards.”

Michael Woods, a gay man who has been a special education teacher in Florida for 29 years, feels like “we’ve gotten in a DeLorean in Back to the Future and gone back to the early 80s”.

If we’re not creating safe spaces for kids, then what are we doing?

He remembers being a confused, closeted child who “didn’t have anybody to talk to”. That only changed when some trusted adults, including teachers, helped him find his way – though he didn’t come out until he was in his 30s.

“I still remember being an eight-year-old kid,” he says. “And if we’re not creating safe spaces for kids, and not passing laws that help kids, then what are we doing?”

Woods fears the impact of ‘Don’t Say Gay’ “will be “so devastating that unfortunately, it won’t be until years from now that we will realise how wrong this decision was”.

The law contains “purposefully vague” language, Woods says, around LGBT+ content being “age or developmentally appropriate”.

“I teach students with disabilities, of all ability levels,” he says. “Of course, we’ve always addressed their needs and made sure that it’s understandable to them, but what what I fear most as an educator is who determines what is age appropriate?

“Because certainly it’s not me. The legislature has made it sound as if we, as teachers, don’t know how to determine what is age-appropriate.”

Donald Trump introduces Florida governor Ron DeSantis during a homecoming campaign rally. (Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

Woods has a master’s degree, is working on his doctorate, and says: “I’ve spent more than half of my life in a classroom, delivering curriculum, developing curriculum, and I always felt like I had a pretty good handle on what was age appropriate, and what was in the best interest of students and what made them successful, and what made them feel safe.”

But now that ‘Don’t Say Gay’ is law, school principals and administrators will have to determine what the vague legislation actually looks like in practice.

This, Woods said, will lead to “very dangerous interpretations, depending on where you are in the state, and who is telling you what they think the law means”.

Bernaert agrees. He says: “The bill is so broad, and it leaves so much open for discretion. You know, what is the line between discussion and instruction?

He says that as educators, their role is to encourage and facilitate discussion. Specifically, Bernaert teaches children to ask “I wonder” questions. At his school, family is a huge focus, and teachers are encouraged to display photos of their own families.

“A prime example is my kids want to know, ‘Who is this other man with you in all these pictures outside of our classroom? … What’s his name? … Mr Bernaert, what is a partner?’

“So, am I having a discussion? Or am I instructing at that point?”

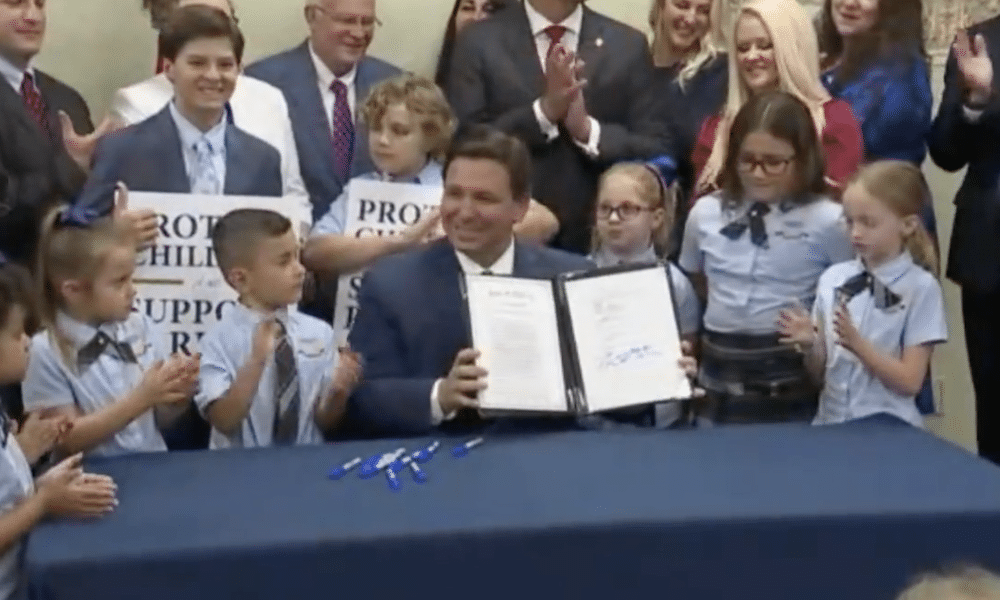

Florida governor Ron DeSantis signed the ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill at the Classical Preparatory School in Spring Hill, Florida. (Facebook/ ABC Action News – WFTS – Tampa Bay)

He continues: “We are going to have students that have two moms, that have two dads… and guess what? They talk to their friends about their home life at recess, at PE, when they’re at lunch.

“Those kids are going to have questions… then they’re gonna go to their teachers and say, ‘Tim told me that he’s got two dads, and I don’t really understand how he’s got two dads.’

“They’re going to go to their teachers about that, because that’s what kids do. We build relationships with our kids, and they trust us to come ask us questions.”

Teachers are afraid of lawsuits

Fear is likely to be a real factor in how teachers approach the new law, making them literally afraid to “say gay” for fear of lawsuits.

Colleagues who teach world history and psychology have been asking Woods what they’ll be able to speak about in class, he said, and some, even veteran teachers, are considering resigning.

Bernaert adds: “I do feel that teachers are going to be mindful because it is now law, and the last thing that an educator wants to worry about is any sort of legal action taken against them.

“Even if that legal action isn’t sound and isn’t going anywhere, I can tell you from experience, you are put on leave, you have to communicate with your local union if you’re a part of it’s a big mess. Nobody wants to put themselves through that.

“The fear is there,” he added. “I don’t blame them. It feels as if we have been bullied.”

‘Don’t Say Gay’ is a ‘solution in search of a problem’

As ‘Don’t Say Gay’ was making its way through the Florida legislature, Woods said he was “surprised”.

“I was surprised because I know the curriculum intimately,” he said.

“I know what we do and do not teach in grades K through three, and none of the stuff that that the bill addresses was being taught, or was even approved to be taught. This bill was a solution in search of a problem.”

Now, Woods is no longer surprised. It is clear to him that the ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill was always “a political move to gain favour rather than really determining what was in the best interest of Florida students”.

“I think the thing that strikes me the most is, for the first time in Florida history, we specifically [enacted] a discriminatory law that that targets one specific, marginalised group of people. By law! It specifically says ‘LGBTQ’ in the law.”

The bill, officially titled the Parental Rights in Education Bill, has told teachers across Florida that they cannot be trusted to do their jobs, and to teach children in a way that is appropriate and in their best interests.

Bernaert said: “It’s really hurtful for me personally and professionally.”

“It really just feels like we, as education professionals, are not being trusted with the curriculum and the standards that are being provided by the state.

“Nowhere in Florida state standards does it say that we are educating children on sexual identity or orientations. So for them to create a bill that try that limits that, it seems like they’re trying to create a solution to a problem that doesn’t really exist.”