How a queer athlete took on the Olympics to create the first-ever Gay Games

Two men wait for the results of their dive at the 2018 Gay Games. (LUCAS BARIOULET/Getty)

In 1982, queer people from across the world congregated in San Francisco to take part in what would become the first-ever Gay Games.

It was a history-making moment for LGBTQ+ people. For too long, many had felt shut out of mainstream sporting spaces because of their sexuality.

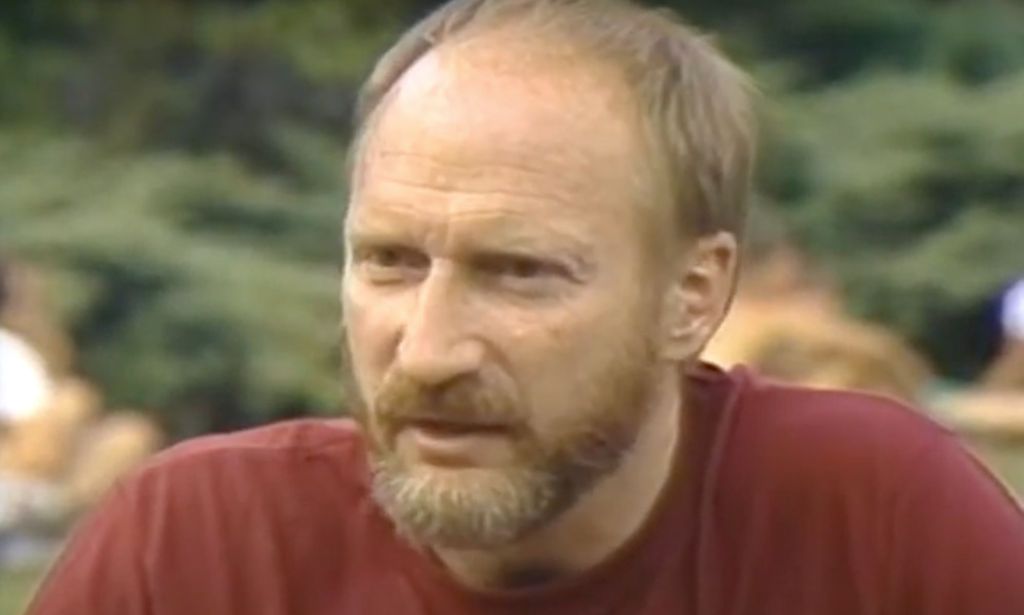

Tom Waddell was one of them. A former Olympic athlete, he dreamed up the idea of the Gay Games after he joined a gay bowling league in 1972.

Right from the start, Waddell faced backlash for trying to organise an international gay sporting event. The games were originally called the Gay Olympics, but a lawsuit from the International Olympic Committee less than three weeks before the games kicked off put a stop to that.

The Gay Games, as they became, went ahead and were a roaring success. Tina Turner performed at the opening ceremony, and Stephanie Mills the closing.

But perhaps the biggest achievement was the enormous number of LGBTQ+ athletes who turned up to participate. 1,350 competitors from more than 170 cities took part in sports that ranged from basketball to powerlifting across the week-long games, which ran from 28 August to 5 September 1982.

Waddell based his Gay Games on the Olympics, but he didn’t carry every aspect over. He didn’t like the nationalism at play when athletes represent their countries, so at his event, participants instead represented their city.

He also banned medal tallies, medal ceremonies and the recording of athletic records. Unlike other major sporting events, the Gay Games were an opportunity to celebrate queer athleticism – not to pit people against each other.

Tragically, Waddell died from an AIDS-related illness in 1987, but his dream lived on. The Gay Games continue to take place every four years – they’ll take place in Hong Kong this November, delayed a year by COVID – and they provide a fascinating blueprint for what can be achieved when LGBTQ+ people create their own spaces.

R Tony Smith has worked with the Gay Games extensively for years in marketing, event planning and, eventually, on its board of directors. He’s also taken part as a volleyball player.

“For me, volleyball is not just a hobby and a sport, but a set of values, and that’s fair play, doing your personal best, and participating – and those three things are the mantra of the Gay Games,” Smith tells PinkNews.

“The mission of the Gay Games is to promote equality through sports and culture, it goes way back to the Black Power movement,” he says, referencing the historic moment when African-American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their black-gloved fists in salute while on the medal podium as “The Star-Spangled Banner” played at the 1968 Mexico Olympics.

“That was the first time, at least in recorded history, that international sports were used as a platform for political and social issues,” he says.

The Gay Games is sport’s version of the gay bar

The fact that Waddell faced pushback at all shows why the Gay Games continue to be so important to this day. Much has changed in the years since those first games, but LGBTQ+ people are still criminalised in many parts of the world.

“Having safe spaces allows us to be who we are. Every one of us in the world, LGBTQ+ or otherwise, the more we’re authentic to ourselves, the more the world is a better place,” adds Smith.

Jon Holmes, the founder of Sports Media LGBT+, echoes that sentiment.

“The wider picture in society at the moment is that there’s a lot of pushback against ways to be more inclusive in sport,” Holmes tells PinkNews.

“The Gay Games goes beyond that. The people [who] compete aren’t just LGBT people, they just happen to have found inclusive spaces in whatever sport and activity they play in, but they love to go to the Gay Games because of its overriding feeling of welcome and comfort.

“It’s like why we go to gay clubs. It’s not that we don’t go to clubs that are nominally for straight people and don’t have a good time – we can still do that – but there’s something so special about being in a place where you know others share that part of who you are and you can celebrate it together in sport.”

That’s particularly important at a time when trans and non-binary people are too often being shut out of sport entirely.

“The discourse around trans inclusion in sport has become even more vitriolic and divisive and major governing bodies are under pressure to renavigate their rules and policies to suit the loud majority,” Holmes says.

“Naturally, the people who are worse off because of that [are] the very few trans and non-binary athletes who maybe thought they’d found a sport for them but are possibly now having to rethink that because of this pressure.”

While LGBTQ+ people wait – and fight – for full inclusion in sport, they at least know they’ll always have the Gay Games, a space where they can be fully themselves, no questions asked.

Above all else, that’s why its mission is still so important 40 years on.