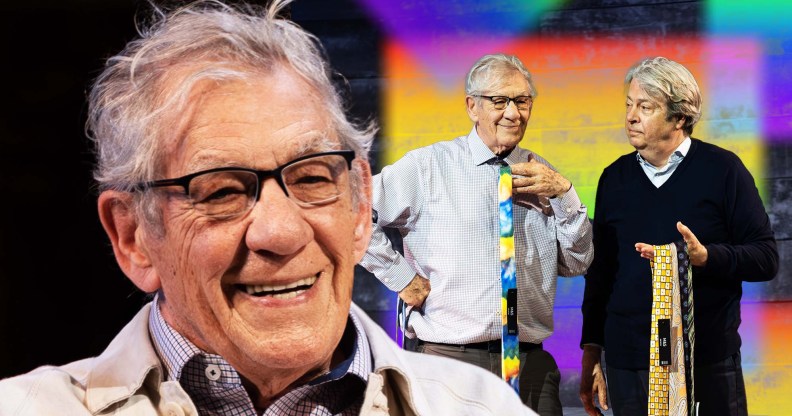

Sir Ian McKellen on starring in gay love story Frank & Percy: ‘It doesn’t get much better than this’

Frank & Percy might be a tender portrait of gay courtship and companionship, but don’t be fooled: the play is very, very funny. (Jack Merriman)

Frank & Percy is the gay love story making waves on the West End stage. Here, its playwright Ben Weatherill and national treasure Sir Ian McKellen talk representation, LGBTQ+ acceptance and the magic of live theatre.

Sir Ian McKellen is quietly confessing that he has a “deep addiction”. It’s not anything remotely shocking or outlandish; but rather something entirely expected from a national treasure who is widely considered to be the finest Shakespearian actor of his generation. The vice in question? Performing.

“It’s a habit, which I enjoy,” he says, speaking quietly, but in the same expressive low key that is so quintessentially McKellen.

Over the years, the inimitable thesp, 84, has found himself returning to the stage time and time again, drawn back by the buzz of standing before a live audience. Unlike making a film, where the cameras can “get right behind the eyeballs”, theatre, he says, is a different experience altogether. “You’re not sitting back watching something far distance. It’s right here. It’s immediate. And it’s live”.

He closes his eyes and smiles. “Mmm. Theatre.”

McKellen might have made it big as Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings series and Magneto in the X-Men films, but theatre remains his first love. In the past four years since he turned 80, he’s trod the boards in The Cherry Orchard, Mother Goose, and two runs of Hamlet.

Now, he’s starring in Ben Weatherill’s Frank & Percy, which premiered in June at the Theatre Royal Windsor and sold out two weeks of shows at the Theatre Royal Bath, before moving to The Other Palace on the West End. Directed by McKellen’s longtime collaborator Sean Mathias, the play tells the story of an unexpected relationship between two older men who meet walking their respective dogs on Hampstead Heath. As it turns out, it was a somewhat unexpected move for the six-time Olivier Award winner, who is casually smoking a cigarette on Zoom from his London apartment.

“I don’t always trust my own taste in things, but the minute I read the script, I thought, ‘Well, this is very, very entertaining’,” he recalls. “I was laughing out loud, which is not the usual thing to do.”

After doing Hamlet and The Cherry Orchard, he rather hoped he wouldn’t be working in Windsor any time soon as it’s an awkward place to travel to. “And yet when Sean sent the play to me without comment, and I said, ‘Are you going to do this?’ And he said, ‘Do you want to be in it?’ And we both said, yes, there I was back in Windsor, which was never a plan. But the play went well there, and even more remarkably in Bath. And here we are in London.”

Frank & Percy is a real “crowd-pleaser” he says, taking a drag on his cigarette. “I’ve not done many new plays, and I’ve certainly not done any new plays that were as instantly successful with audiences as this one. So it’s a joy to go in every day. I look forward to it.”

The play follows Frank (Roger Allam), a retired history teacher who strikes up an unlikely friendship with Percy (McKellen), a sociology professor, while walking their four-legged friends. Inspired by the power of everyday interactions during the pandemic, Weatherill, who joins us over Zoom, began to consider how the most mundane of encounters could be utterly transformative.

“I think I was, like everyone, feeling a bit lost, lonely, unsure of things, and spending a lot of time with dogs,” he remembers. “And it was very literal in that way. I started to think about these two chaps who were lonely for their own reasons, and they came together. I started to think about, Well, what if they changed each other in quite a large way? What if this small interaction actually expanded out into something that was big and beautiful and knotty and heartwarming?”

Getting the play off the ground wasn’t without its challenges: after receiving a string of rejections from theatres (“they weren’t interested”), Weatherill’s agent suggested they change tack, and encouraged him to reach out to people he was genuinely interested in working with. “I said, ‘Well, why don’t we try and send it Sean?’ So I wrote him a letter, and one of the themes of the play is letters.” He smiles. “I attached a picture of my dog to it, Audrey. I said ‘He’s not going to say no to a cute dog’.”

“I didn’t know about all this!,” chuckles McKellen. “You knew your way to Sean.” He would know: Mathias and McKellen first met at the Edinburgh Fringe in 1978, and began a romantic relationship until parting ways in 1988. In the 35 years since, Mathias has directed McKellen in over thirty productions, including the award-winning 1997 film adaptation of Bent, 2013’s Waiting for Godot with Patrick Stewart, and a feature film version of his 2021 Hamlet last year.

If Weatherill’s approach was tactical, however, it had the desired effect: within a couple of weeks, he received a phone call confirming that Mathias wanted to do the play. The following day brought even better news: Ian McKellen was up for it, too. It was nothing short of “surreal”, laughs Weatherill, not least because he was working as a head of year in a high school during the pandemic. “I was on lunch duty. There was about a thousand students having lunch, and I got a phone call from my agent saying, ‘Yes, Ian McKellen wants to do your play’. And I was very, very thrilled, as you can imagine.”

In the end, Weatherill ending up snagging not one but two stage titans, with the addition of three-time Olivier award-winner Roger Allam. “They were very generous towards me,” says Weatherill, who was there every day in rehearsals. “I just tried to be like a sponge and soak as much as possible.” For McKellen, the reunion with Allam was “blissful”.

“We became great friends when we were doing Abbanaza and Widow Twankey in Aladdin at The Old Vic,” he recalls. Since then, the pair have developed a close friendship, and McKellen now considers himself part of Allam’s “domestic life and lovely family”, he explains.

“There’s a line in a film I did called Gods and Monsters, when I was playing a gay director. And he says, ‘Making movies is the most wonderful thing in the world’. Working with friends, and the same, of course, is true in putting on a play. And that’s exactly what we’re doing here. We’re working with friends and entertaining people. It doesn’t get much better than this, really.”

For a play that begins with light exchanges about hip operations and hearing aids, Frank & Percy covers plenty of ground as the two lonely gentlemen graduate from friendship to romance. Alongside discussions around ideological differences and freedom of speech, marriage and mortality, the evolution of Frank and Percy’s relationship – complete with still-active sex lives – is an important reminder that desire remains strong after middle age.

“I think of it as quietly radical,” says Weatherill, who has form when it comes to giving voice to underrepresented groups (his 2018 romantic comedy Jellyish centres a heroine with a learning disability). “We don’t often see older people fall in love, let alone older queer people. And I think that’s always interested me. Love stories are where my bread and butter is at, but it’s who gets to fall in love and who do we see? For the majority, the whole narrative of society, we could say, is heteronormative, so actually, let’s have a look at these stories that we haven’t unearthed yet. I think that’s interesting.”

Frank and Percy, however, represent different sides of the LGBTQ+ experience. While McKellen plays a character who is explicitly and unapologetically gay, Frank is coming to terms with the realisation that his same-sex attraction must make him bisexual. “Roger does it very beautifully,” notes Weatherill. “There’s this older chap who has outwardly been one thing all his life, might have had curiosities or questions or something that hasn’t been explored, and then through meeting Percy, by chance, he’s able to flourish. I think that’s gorgeous in many ways.”

As much as it’s a gay love story, though, he didn’t want representation for representation’s sake. “The moments when they’re talking about their sexuality, hopefully are there to further them as characters.”

Case in point: a joyous scene where Frank and Percy prepare for Pride, which sees McKellen don a tiny rainbow-coloured tutu and a red t-shirt bearing the slogan ‘Some people are gay. Get over it’, made famous by Stonewall’s campaign challenging homophobic attitudes to LGBTQ+ people. What the audience doesn’t know, McKellen explains, is that the t-shirt is his very own.

“At that moment, I am both Ian and Percy, our lives momentarily cross,” he explains. “And that an audience should so easily accept the intimacy between two people, which is not to be expected when the play starts, is very, very heartening.” Public attitudes towards homosexuality have certainly come a long way since he came out in 1988 at the age of 49 to fight Section 28, Britain’s reviled Thatcher-era law that forbade local authorities and schools from “promoting homosexuality”. That same year, he co-founded Stonewall, now the UK’s most prominent LGBTQ+ rights organisation, and has been at the forefront of gay rights activism ever since. Behind him, a small Pride flag pokes out from his bookshelf.

“In my lifetime, changes have been total,” he says. “I first kissed a man on stage in 1969 in the production of Edward II by Christopher Marlowe. That’s the first play in our language to have a gay hero. When we did the play in Edinburgh, a local councillor tried to ban our production because of the enormity of that moment, where two men kiss, which he thought was inappropriate to take place on the public stage. Well, his objections were widely reported, and I think helped to make the production a complete success, because there were many people who disagreed with him”.

McKellen points to a climactic end-of-first-act moment in Frank & Percy where the two characters share a passionate kiss. “The change now between that and the kiss in this play, which the audience welcomes and understands, and approves of, is remarkable.”

It’s this emotional connectedness that sits at the heart of the play. Whether Frank and Percy are exploring what it means to age in society, finding love again later in life, or the state of the NHS, every interaction reveals how the two charming curmudgeons relate to one another. “There’s a scene where they disagree about a political opinion, but that’s actually really about how they’re connected to individuals,” explains Weatherill. “There’s a scene where they argue over their dogs, but actually it’s about their relationship. I think that’s why it covers so much ground, because actually, a relationship is never just based on one thing. It’s a multitude of things that come together to connect you. I think that’s what I love about the play, is two men isolated alone, and they save each other through conversation.”

Frank & Percy might be a tender portrait of gay courtship and companionship, but don’t be fooled: the play is very, very funny. Amongst the exchange of pleasantries and offstage barks from the couple’s dogs, both actors are able to showcase their brilliant comic timing and Yorkshire accents; McKellen mischievous as ever as he cracks risqué one-liners about a dexterous tongue and deep throating a cucumber, Allam hilariously caustic as he contemplates life’s simple pleasures such as karaoke (“I’d rather staple my face to a moving train”).

Weatherill, who grew up watching the late comedian Victoria Wood, says the humour has an undeniable “Northernness” about it. “I think my ear has always been tuned to that style of dialogue,” he says. But many of the play’s jokes, he adds, came about organically. “Ian and Roger found moments that I didn’t expect to be funny. Some of the moments are just a look between the two of them whilst they’re sharing a Pontefract cake. I can’t script that.”

Weatherill may be modest about his talents, but McKellen is effusive in his praise of the young playwright. “It’s not often you do a play where people burst into laughter and sometimes applaud at certain moments or lines,” he says. “I’ve often said that Alan Ayckbourn and Alan Bennett come to mind as you’re reading Ben Weatherill. It’s in a tradition of plays that use humour and laugh aloud laughter to reveal people”. It should be noted, he adds, that Weatherill comes from Leicester, the same city as renowned comic playwright Joe Orton, who also penned funny, radical plays in his early 30s. The “dark humour” of Loot and What The Butler Saw appealed to Weatherill, alongside other plays that his drama teacher introduced him to, such as John Osborne’s Look Back In Anger and Andrea Dunbar’s Rita, Sue and Bob Too.

In other words, British plays that are “naughty and a bit dark, and a bit filthy, and are asking difficult questions”.

Frank & Percy is also a reminder of the positive influence that teachers can have on a person’s life. “Frank is in the thick of teaching, trying to make an impact on his individual students,” says McKellen. “Percy, being a professor and a writer, is a bit, although it’s his work that gets cancelled at one point.”

It’s another way the play is relevant to our lives, he says. “Teachers are so precious. Here we have a play about teaching, which is perhaps the most honourable, necessary job, at the time when teachers are a bit beleaguered, let alone other minorities”.

It’s perhaps inevitable, though, that the biggest talking point of Frank & Percy is two older men getting intimate. After all, the representation of older queer people in intimate relationships are rare, if not absent altogether, in mainstream media. “I think it’s important to keep telling these stories,” says Weatherill. “I think if theatre is used as a vehicle for change, then it’s surely putting lives under the microscope that help us understand people.” In a political climate that has become increasingly hostile towards LGBTQ+ people, he says he tries to remember that “the average person on the street does have a live and let live attitude”.

There’s perhaps no better proof of that than the way audiences have responded so enthusiastically to Frank & Percy. Here, McKellen chimes in to say that he has been told by countless people – “usually older generations” – that they have never enjoyed an evening of theatre as much as they have while watching Frank & Percy. “That is unusual,” he says emphatically. “It just confirms what I’ve always known, that people who go to the theatre and like the theatre are very nice people. I wish the whole nation shared their openness and welcoming to the different and the individual and the unexpected.”

Come the new year, McKellen is planning to do a new production. “Not ready for announcement just yet, but there does seem to be another job I’m going to have to do before the inevitable,” he says. “The inevitable being not being able to work anymore. I’m doing it while I can.”

For now at least, he won’t be dipping into the wings any time soon. “Sometimes when I come into the empty auditorium at the beginning of the evening and look down at our set, I think: ‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful just to work here all the time and put on another play and another play and another play?’ Because when you do theatre, which has this built-in intimacy, all is changed.”

Frank & Percy runs at The Other Palace until 17 December. Find out more here.

How did this story make you feel?