The Lost Boys director on telling a different kind of queer love story in youth prison romance

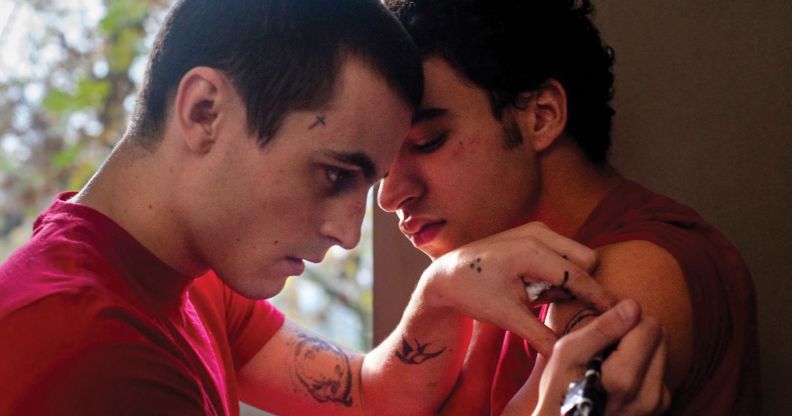

William (Julien De Saint Jean) and Joe (Khalil Ben Gharbia) in Zeno Graton’s queer film The Lost Boys. (Kris De Witte)

Queer Tunisian-Belgian director Zeno Graton speaks to PinkNews about his tender, politically-charged feature debut The Lost Boys, reframing masculinity, and the future of queer cinema.

Growing up in Brussels, 33-year-old film director Zeno Graton witnessed firsthand the contempt with which young offenders are treated. After his cousin was jailed for minor offences, Graton saw how people with their whole lives ahead of them are written off by a system entrenched in systemic racism, often leading them on a one-way road to prison.

Buoyed also by his desire to change the face of queer cinema by telling stories that aren’t about coming-of-age or soul-crushing violence, Graton wrote and directed The Lost Boys, a quietly intense French language film about two young men who fall in love within the walls of a juvenile detention centre.

Joe (Khalil Ben Gharbia) is listless in his attempts to leave the centre, knowing that what awaits him on the other side is equally as bleak. When the slightly more unruly William (Julien De Saint Jean) arrives, the pair take an instant shine to one another.

From then on, they are each other’s safety net as they struggle with the rigid and frequently cold way of life in juvenile detention. Through moments of hopelessness, they provide each other with a centre of gravity, an escape, a promise that joy and passion can still be had despite how society might cast them aside.

PinkNews: Hi Zeno. I know you spent some time in a youth detention centre to speak with some of the young people who have been incarcerated. How did that experience inform The Lost Boys?

Zeno Graton: Most of the things that you see in the film [are things] that I witnessed. The public opinion on these centres [is] really black and white. Nobody really knows what happens behind these walls. It’s [viewed as] either a gulag prison where the kids die, or a vacation centre where they can do whatever they want. I really wanted to portray something in between.

PinkNews: We see Joe, William and the other boys coming alive when they get to play music and paint. Is that the reality you saw?

Zeno Graton: Yes, they have a lot of artistic activity. What I saw is that the educators in the centres, they try 100 per cent to work for the kids.

The problem is more about the system around it, the discrimination system from the schools, the renewal of the stays [at the centre] that are very arbitrary, the parents who abandon them.

It’s a whole way of thinking from our society about how we treat people who did [crime] in youth. I think what we’re going to continue to do is just put them aside, put them in the margins, waiting for them to be old enough to go to prison, not caring about how we reinsert them in society, not caring about the fact that their delinquency is linked to a multifactorial, systemic stain that is crossing gender, race and class.

PinkNews: The story of youth incarceration could easily have been told through a heteronormative lens. Other than the fact that you are queer yourself, why did you want to tell it through a queer perspective?

Zeno Graton: I wanted the obstacles of the love story to be external; for the walls to be outside and not inside of them. I think in a lot of queer narratives in cinema, especially in the youth characters, the main conflict of the film is the overcoming of inhibition and shame.

These stories are completely relevant, and I’ve loved so many films about that, but I felt it was time to propose new stories. I really wanted the characters to not be ashamed of themselves.

PinkNews: Is that why you opted for the first intimate scene between Joe and William to come early on in the film, quite unexpectedly?

Zeno Graton: It was to tell the audience that this was not going to be a film about whether or not they’re going to be able to be together.

In those stories, it’s often the case – it happens at three quarters of the movie. In my life, after I [came out], the main conflicts were ahead. Nobody [told] me that it’s f*****g hard to love and be loved and create a relationship that can last.

So I was more interested in creating a story revolving around passion, abandonment, all these conflicts that come when you are in love.

PinkNews: There are a lot of beautiful shots in The Lost Boys but is there one scene you found particularly rewarding to create?

Zeno Graton: This whole film was a joy. I want to talk about the sex scenes: we hired an intimacy coordinator and this was the best thing that could have happened for me.

There are three moments where Joe and William have interactions and [the intimacy coordinator] was so good, not only to make them feel safe, but also to have new ideas. They asked me what I needed for the scene and then they brought up so many ideas that I never could have.

I want to encourage everyone to hire them, not only as a token for good behaviour, but really [because it’s] rewarding.

PinkNews: There were a few scenes where the intimacy between Joe and William is communicated in just a touch. Was that on the direction of the intimacy coordinator?

Zeno Graton: It was more from the fact that I really wanted to show tenderness. In queer narratives, since there’s so much shame and inhibition, the sex scenes are always brutal in order to portray the fact that they’re not OK, they’re bad, [they’re] feeling ashamed.

I wanted to take a counterpoint on that and show that two people can actually love each other in a very tender way. For me, it was more subversive to show tenderness than sex.

PinkNews: There is a lot of tenderness between the other young men in the detention centre, too. Not in an intimate or romantic sense, but they embrace each other without hesitation. Why did you want to include those scenes?

Zeno Graton: I really wanted to portray alternative masculinities. I wanted to show boys that could be boys differently, boys being able to be tender to each other, to show solidarity, to cry, to long, to be missing people they love. This makes them men too.

PinkNews: What would you hope the future of queer cinema looks like?

Zeno Graton: My dream is that we can have queer characters in films [where] their storylines don’t revolve only around their queerness. It’s happening, but I wish it would happen more.

I’ve seen this English series, It’s A Sin – oh my God. These things are so important because we have a history, and the AIDS history, for example, was so [ignored that] I even didn’t know what was going on at the time. It’s a story that we’re not told by the mass media, so series like Pose, It’s A Sin, are crucial. I think there are more untold queer stories from the past that need to bubble up.

PinkNews: There is a powerful scene where Joe recounts his experience of racism in France as a young man of Arab descent. Can you talk us through why it was important for The Lost Boys to be led by a queer Arab character?

Zeno Graton: I wanted to portray a queer leading Arab character to really [show] a queer character that would not be fetishised or exoticised, neither victimised. This is always a narrative that we get. I’m half Tunisian; I was tired of seeing that. It was very important for me to have someone who had drive of his own, who went for his desires.

When I saw It’s A Sin, for example, you see a Black character in the beginning (Roscoe Babatunde, played by Omari Douglas), who gets out of his home, he slams the door, and he’s so fierce. I’m like, where are [those characters]? I was so thankful to see that.

Also, when I think about Euphoria where you have Zendaya, there’s never a question about the fact that she’s Black and she’s in love with a trans girl. There’s never an issue about race or about gender. I was like, f**k, this is so refreshing. It was very inspiring.

The Lost Boys is in cinemas and on digital on 15 December.

This interview is condensed for clarity.