Newly-unveiled Alan Turing sculpture in Cambridge divides opinion

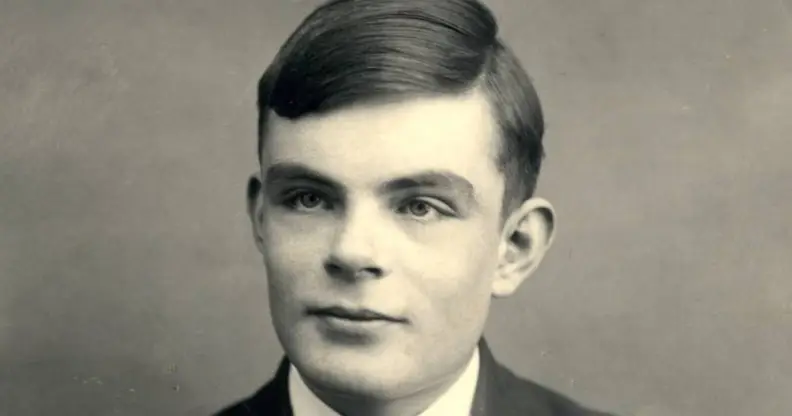

Alan Turing took his own life after being convicted of gay sex offences. (Getty)

A newly-unveiled sculpture of war-time code-breaker Alan Turing has received a mixed response.

Erected at King’s College, Cambridge, where the gay scientist studied maths in the early 1930s, the sculpture has caused controversy for its abstract design.

Turing’s work at Bletchley Park, where he helped crack Nazis Germany’s highly complex Enigma code, is credited with helping shorten World War Two, thus possibly saving millions of lives. He also laid the foundations for personal computing and artificial intelligence.

Despite all this, he agreed to be chemically castrated – rather than go to jail – after being convicted of gross indecency with a man in 1952. He took his own life two years later, aged just 41.

Nearly 60 years later, Queen Elizabeth II formally pardoned him, following a concerted campaign.

However, in 2022, The Historic England Planning Commission weren’t quite so understanding when it came to erecting a statue of him, originally claiming: “We consider it would harm the particular character, created by the interplay of buildings and landscape, which makes the college so remarkable a place,” they wrote in a letter to the Cambridge City Council, according to LGBTQ Nation.

Now that the sculpture, designed by Sir Antony Gormley – best known for his Angel of the North – has been unveiled at Alan Turing’s former college in Cabmridge, people have taken to X/Twitter to criticise it.

One person simply wrote: “What an awful sculpture.”

Another said: “Not a fitting remembrance of a once-living man, but a piece of ‘modern-art’ trash. I’m amazingly disappointed once again at what’s considered good public sculpture now.”

Others branded it “sad” and “very bizarre.”

But the statue, which stands 12.1ft (3.7m) tall, won praise from others, with one person saying it captures Turing’s “single-minded brilliance”.

During the unveiling ceremony, Gormley admitted that he had been worried “it wasn’t controversial enough”.

Following laughter from the audience, he added: “I’m amazed by the way the sculpture speaks to the buildings, and the buildings to the sculpture. They’ve immediately entered a kind of dialogue.

“I have to say, it took a long time to get here. It was 2015 when the journey started, and the planning permission was perhaps the biggest hurdle, [al]though everyone agrees it looks like the sculpture has always been here.”

It was not meant to be a “memorialisation of a death,” he added, “but about a celebration of the opportunities that a life allowed”.

The sculpture, made of steel and copper so that it will oxidise into a deep red colour in the future, is a series of blocks, designed to portray a man’s figure.