Ghana anti-LGBTQ+ bill could spark ‘witch hunt’ for queer people, says activist

Queer activist Prince Frimpong fears a proposed new law approved by Ghana’s parliament will lead to “witch hunts” for LGBTQ+ people and allies in the West African nation.

Ghanaian lawmakers approved a draconian bill last month that would mean queer people being imprisoned for up to three years for merely identifying as part of the community. Additionally, it would criminalise the “wilful promotion” of “LGBTQ+ activities” and any failure to report an LGBTQ+ person to the authorities.

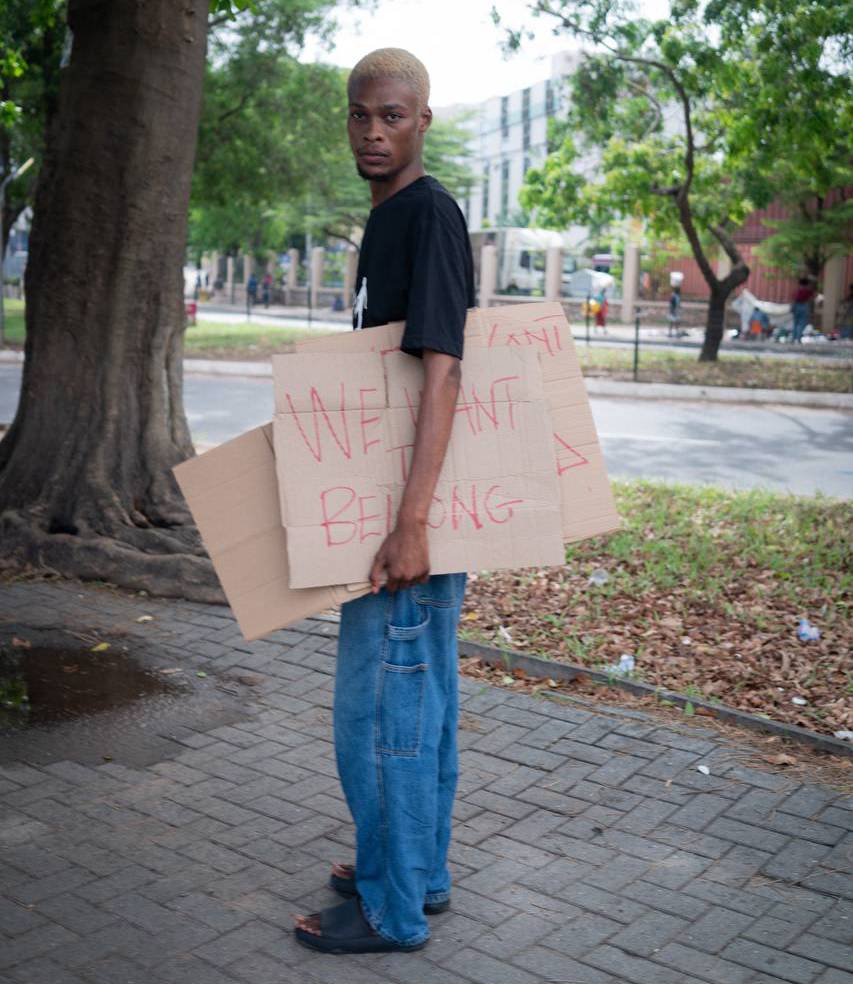

Protestors gathered outside the country’s High Commissions in London and elsewhere around the world on 6 March – Ghana’s Independence Day – to urge president Nana Akufo-Addo not to sign the bill into law.

Even though the bill hasn’t taken effect yet, Prince Frimpong, an activist with Youth Initiative Foundation, tells PinkNews there have already been direct repercussions.

The day after parliament’s decision, Frimpong claims one of his friends was stopped by boys in his neighbourhood who “called him names and assaulted him”, with the campaigner noting that “nothing of that sort” had happened before.

“This kind of abuse is like a witch hunt. In our culture, we call it this because we’re being hunted, and someone will just point and say: ‘witch’. Then they will investigate the person just [on] hearsay,” Frimpong claims.

“That is exactly what is happening in Ghana. You could just be walking around, and someone will just call you, ‘gay, gay, gay’ and, all of a sudden, you’re being beaten.

“That is the direct repercussion of what the bill seeks to do. The bill is bringing an era of slavery where we don’t choose who we are, where we associate ourselves.”

Frimpong believes the bill will “enslave” queer people and be “used to steal our constitutional rights” by “wiping and erasing our identity”.

Ghana’s anti-LGBTQ+ bill hangs in the balance amid court rulings

President Akufo-Addo has said he will wait for a Supreme Court ruling on the proposed legislation’s constitutionality before taking action.

He acknowledged that it “raised considerable anxieties” about Ghana “turning her back on her, hitherto enviable, long-standing record on human rights observance and attachment to the rule of law”.

Ghanaian religious leaders, local LGBTQ+ groups, international human rights groups and the UN have condemned the bill, and even Ghana’s finance ministry urged the president not to enact it.

Frimpong says his heart is “so heavy” as anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment mounts in the West African nation. He thinks the legislation was “literally for the politicians” because its benefit to Ghanaian society has “yet to be discovered”.

Queer Ghanaians already face discrimination, stigma and violence

Ghana’s current anti-LGBTQ+ law, derived from British colonial-era legislation criminalising “unnatural carnal knowledge”, imposes a maximum three-year prison sentence for same-sex sexual activity.

The recent push for harsher penalties has seen queer activists arrested, people subjected to violence and threats and resources for the LGBTQ+ community shut down.

Frimpong says it was “really hard to get to know” or “discover” his queer identity growing up in such an environment. In one instance, when he was 17, his mother called the police as a way to “punish” him for being part of the LGBTQ+ community.

“One morning, I was just there, and the police came into the house, took me to the police station and asked me lots of questions: who I was having an ‘affair’ with.

“I also [suffered] several assaults from the policemen and my mum… I remember signing a document or contract. Because I wasn’t 18, they couldn’t charge me with ‘unnatural carnal knowledge’ or charge me, because I was a minor.

“What they could do is let me sign a document of good behaviour, and I would tell them that I’m not going to go back to being gay or all those kinds of stuff…

“It had a toll on me, it still haunts me. I’m just fortunate I don’t live with my parents any more because this bill would do more harm than good.”

Frimpong believes existing issues around queer people’s lack of access to housing and employment would be exacerbated by the legislation. He also fears queer people will stop going to hospitals because they won’t feel “safe with whoever is taking care of them”.

He goes on to say: “The effects are tremendous. Words can’t explain the effect this is going to have on the entire LGBT community and the entire Ghanaian community. I fear Ghana would not recover if the bill is enacted into law. Trust me, generations to come: we can never recover from this act.”

Frimpong urges people to help LGBTQ+ Ghanaians to keep fighting by sending aid, advocating at the UN, protesting to make sure “a lot of voices” are “at the table” or holding politicians accountable for supporting the bill.

“You might think your actions aren’t enough, but it is enough,” he says. “Just one action could change something because creating or influencing change is a stepping stone. It’s one step at a time.”

With partners in Ghana, including Frimpong, global advocacy group All Out have started a campaign calling for the bill to be rejected. So far, more than 77,000 people have signed it.