Sorry ‘gender critical’ trolls, you can’t tell someone’s sex by their pelvic bone. Here’s why

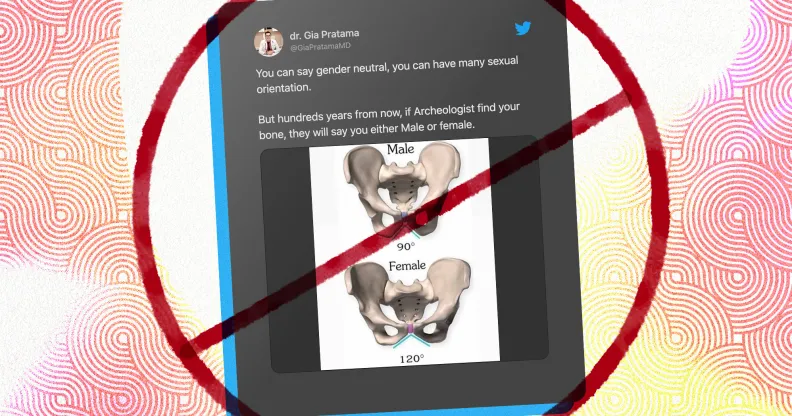

The popular ‘gender critical’ theory about pelvic bones is simply nonsense. (Credit: GiaPratamaMD | Twitter)

It’s a popular ‘gender critical’ argument, that if archaeologists were to dig up a skeleton in hundreds of years from now they’d be able to tell whether it was male or female.

Sadly for them, it’s total nonsense.

The belief that birth sex is identifiable through skeletal structure is entirely “misleading” according to various experts.

The myth became popularised by so-called gender-critical individuals following claims of a physical disparity between pelvic bones of those assigned male at birth and those that were assigned female.

It is routinely used as an argument by anti-trans groups to claim that the concept of gender identity is useless because of its impermanence.

But, according to several experts in archaeology, the claim ignores a number of fundamental steps when identifying skeletal remains.

ATSU assistant professor and biological anthropologist Caroline VanSickle told AFP that professionals often cannot say with any certainty if an individual was male, female or other just by looking at their bones.

“We can offer a fairly educated guess, but even then we sometimes get the answer wrong or end up with inconclusive results,” VanSickle says.

She added there is currently “limited data” on how hormone replacement therapy (HRT) affects bone structure, which makes it even more tricky to define the facts about a centuries-old skeleton.

“We also lack methods to identify intersex individuals, who make up around two per cent of the population,” she added.

The pelvic bone is not reliable enough to identify a male or female skeleton

Because of this ambiguity, archaeologists often refrain from definitively identifying the sex of a skeleton unless there is further proof to corroborate the decision.

When examining a skeleton, Osteoarchaeologists often consider both the physical characteristics of the skeleton, while also considering evidence of the person’s gender identity – especially in cultures which have exhibited gender-neutral or third-gender identities.

Durham university archaeology professor Rebecca Gowland said that skeletons are often categorised as male, probable male, unknown, female, or probable female.

She said the categorisation is based “on a number of different factors… [including] poor preservation, or it could be that some of the skeletal traits used to estimate sex are ambiguous.”

Sexual dimorphism – the biological or physical difference between the sexes of a species – is reportedly so slight in the skeleton of a human that the margin of error can be exceptionally high.

Gowland added that professionals are aware “biological sex exists on a spectrum, of which skeletons and the sexual variation they show is only one part of a greater whole.

“They also understand that the assessment of sex using skeletons is not 100 per cent accurate and this analysis may not align with an individual’s biological sex or gender identity.”

But, as many trans activists have pointed out, the concept of being misgendered in hundreds or thousands of years from now is not exactly on the top of their anxieties list.

“I won’t be alive by then, so I don’t really care,” journalist Katelyn Burns said in response to a post using the argument.

“Oh no! I’ll be so embarrassed when my bones are dug up in several hundred years! What ever will I do!?” another sarcastically wrote.

Others simply replied: “I’m getting cremated.”

How did this story make you feel?