How the decriminalisation of homosexuality set Ireland on a rapid, awe-inspiring path to modernisation

It’s been 30 years since Ireland decriminalised homosexuality. (Getty/PinkNews)

On 24 June 1993, homosexuality was finally decriminalised in Ireland after a lengthy and tiresome battle.

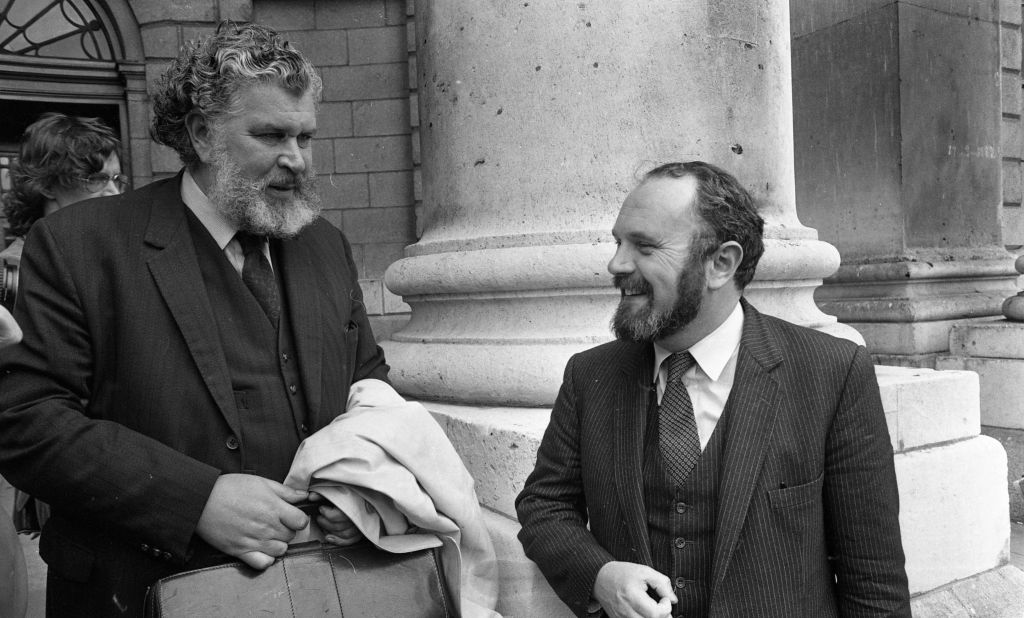

It was a long fight to get to that point, and it would never have happened without the exhaustive efforts of David Norris.

At at time when many queer people were still living in a state of secrecy, Norris took a series of highly publicised legal cases challenging the law that made it a crime for him to live and love openly.

After his cases were struck down by both the High Court and the Supreme Court in Ireland, Norris took his case to the European Court of Human Rights, where he finally emerged victorious in 1988.

After a lengthy five year wait, the Irish government finally decriminalised homosexual acts in 1993. It didn’t get rid of the many injustices queer people faced in Ireland on a daily basis, but it helped, at the very least, eradicate the spectre of criminality from queer life.

It’s easy with hindsight to downplay the significance of the decriminalisation of homosexuality in Ireland, but the truth is that it represented a seismic shift for a country that had been steeped in Catholic doctrine ever since it gained independence from Britain in 1922.

Under the Catholic Church’s thumb, the Irish Free State – which would later become the Republic of Ireland – was a particularly punishing place to exist if you happened to exist outside of society’s strictly enforced norms. If you were a woman, working class, a child or a gay man, you risked imprisonment or incarceration in one of Ireland’s many institutions, from Magdalene Laundries to industrial schools and prisons.

It wasn’t until the latter part of the 20th century that the strictly enforced moral code of the Catholic Church started to crumble. In the 1970s, both the Irish Women’s Liberation Movement and the Campaign for Homosexual Law Reform were founded, showing that an increasingly vocal minority were intent upon tearing up Ireland’s rule book.

Even so, it would be foolish to claim there was some kind of linear progression from the 1970s onwards. In 1983, the Irish people voted overwhelmingly in favour of a constitutional ban on abortion. That same year, a teenage girl by the name of Ann Lovett died in a grotto dedicated to the Virgin Mary during childbirth. It later emerged that she had concealed her pregnancy from everyone around her.

It was a dark time, but finally, things started to change with the dawn of the 1990s. Following the decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1993, divorce – which had up until that point been prohibited in the constitution – was legalised in 1996. In the same year, the last Magdalene Laundry shut its doors in Waterford. Ireland would later find itself the focus of international news as stories began to trickle out detailing the horrors women had been subjected to in those institutions.

Ireland was slowly starting to more closely resemble other countries in the European Union – but it still had a lot of catching up to do – and politicians weren’t always eager to drive change at a legislative level.

In 2011, Ireland legalised civil partnerships after yet another long, exhausting campaign – but by the time it finally happened, the conversation had moved on entirely. Most queer people had decided that civil partnerships were not enough – they wanted equal marriage.

Ireland legalised marriage equality after bitter, bruising campaign

The marriage equality campaign began in earnest. Because the constitution defined marriage as being between a man and a woman, it was decided that a referendum would have to be held. In a cruel twist of fate, Irish queer people were forced to go door-to-door, asking their straight counterparts to vote in favour of marriage equality so they could get married.

It was a bitter and often cruel campaign. Posters littered streets all over the country telling people that “mothers and fathers mattered” and that allowing gay men and lesbians to marry would destroy the foundations upon which marriage was built.

The Irish public didn’t buy it. In May 2015, they voted overwhelmingly in favour of same-sex marriage. International media looked on in awe and confusion. Many wondered how a country that had for so long been one of Europe’s Catholic strongholds had gone from decriminalising homosexuality to legalising same-sex marriage in the space of 22 years.

The same year, a notably progressive Gender Recognition Act (GRA) was passed after a long battle from Dr Lydia Foy. To say it was long overdue would be an understatement – the High Court had ruled in 2007 that Ireland was in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) by refusing to allow Foy to have her gender legally recognised.

Three years later, Catholic Ireland was dealt perhaps its most decisive blow when the Irish public voted overwhelmingly in favour of striking down the constitutional ban on abortion. Once again, breathless media coverage questioned how Ireland had changed so quickly.

The answer, at least in part, lies with the activists who decided that enough was enough. People like David Norris and Dr Lydia Foy dedicated much of their lies to fighting the state – and they never backed down.

To say much has changed since homosexuality was decriminalised 30 years ago would be an understatement. The Republic of Ireland is a radically different place today than it was in the early 1990s, for both queer people and for women.

As we mark 30 years of decriminalisation, there’s plenty to celebrate – but there’s also much more to be done to make Ireland a better, safer place for queer people to exist.

Perhaps by the time the 40th anniversary rolls around, there will finally be robust hate crime protections in place. Perhaps the GRA will have been reformed to recognise non-binary identities, and maybe something will have been done about the desperate state of trans healthcare in Ireland.

Three decades on, a lot has changed – but the battle for full equality is far from won.