Movies That Made Me Gay: Exclusive extract from Larry Duplechan’s witty new memoir on how cinema shapes queer identity

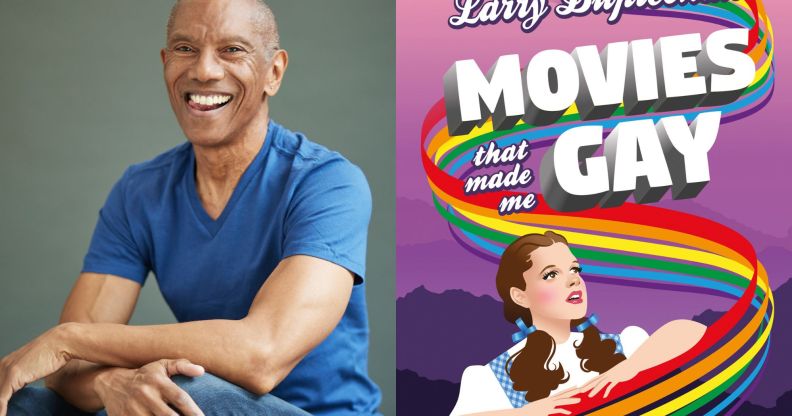

Larry Duplechan’s new memoir Movies That Made Me Gay is out now. (Supplied/John Farrell Jr)

In his new memoir Movies That Made Me Gay, landmark American novelist Larry Duplechan reveals the Hollywood films and stars that helped to shape him as a Black, gay man who grew up in the 1960s.

Described as “witty”, “funny” and “wise”, Movies That Made Me Gay is a guided tour through Duplechan’s life, including surviving the catastrophic AIDS crisis of the ’80s, and seeing his 1986 novel Blackbird turned into a film by Patrik-Ian Polk in 2014, starring Oscar winner Mo’Nique.

In this exclusive extract from his new memoir, the queer, Black icon Larry Duplechan celebrates the power of cinema in shaping queer identity.

Of course, I don’t mean any movie turned me into a man who likes men (likes them quite a lot, in fact): I am confident my gayness originated in utero.

I realised I liked boys, and grown men, quite early – I had a homoerotic dream about singer Rick Nelson (of The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, which sitcom I watched as a child) before I’d even started school: Ricky was singing “Hello Mary Lou (Goodbye Heart)” on a television soundstage, buck naked, his guitar hiding the goodies up front, his bare buttocks undulating in time with the music (yes, my dream camera panned around to show Ricky’s rear).

My first serious crush on a boy (as I recall) dates back to the fifth grade (so, 9 or 10 years old) and a ginger-haired Cub Scout named David Waterson (and wherever he is, he should live and be well).

So I think it’s a safe claim that I have always been gay. And I was a sissy, as my schoolmates and neighbor kids reminded me every chance they got: slender, high-voiced and, due to skipping half a grade early in my school career, perpetually smaller than my classmates.

I couldn’t play sports – any sports – and was vocally uninterested in them. For a Black boy growing up in the 1960s and ’70s in and around Southern California, I was a decidedly odd child. But movies – especially “classic” movies from the 1930s through the ’60s, shown on television (local stations and network affiliates; afternoons, evenings and on The Late Show) throughout my childhood and teen years, viewed, re-viewed and loved by me for nearly as far back as I can recall – movies gave my youthful oddness a certain … flair.

I affected the speech and mannerisms of favorite stars, almost always women: Julie Andrews’ posh Brit accent, Kate Hepburn’s lockjaw Yankee bray, Barbra Streisand’s Brooklynese. I’d hold a pen as if I were Bette Davis wielding a cigarette. I guess if you’re a weird kid anyway, you may as well Go Big or go home.

By high school, I had affected what I’d hoped was a faithful cover of that peculiar accent-that-is-no-accent American English spoken by many of the lead actors in the classic movies I loved. I didn’t speak like my parents (both born in rural Louisiana during The Great Depression), or really much like anyone else not under contract to Paramount circa 1942. I peppered my conversations with anachronisms like “Hiya, toots!” and “I daresay”.

By 14 years old or so, (when I started high school), among other artsy kids in choir, band and theater, I had not only found a sub-community where suddenly dropping into a Cockney accent for a sentence or two wasn’t that big a deal, and the ability to recite wads of dialogue from The Lion In Winter actually gave one a certain cachet, I had also discovered that certain words that had been hurled at my head since elementary school – oh, you know the ones I mean – actually meant something; something I felt, something it seemed I was.

So when I claim that, say, Stage Door (RKO, 1937) made me gay, I really mean Eve Arden’s deadpan delivery of lines like, “I predict a hatchet murder before the night’s over” showed me a style of humour I could, and did, emulate.

If a kid in class took a long time to grasp a concept, for instance, once he did grasp it, I could drily quote Ann Miller’s “And then came the dawn”, convulsing the two kids to either side of me – who might be chastised by the teacher for laughing, but no one else would have heard me say anything.

Which became my stock in trade: I was funny. Not Class Clown, mind you: Class Wit. Other boys might be more handsome than I, a few more intelligent, and almost every boy was more athletic; but I – almost solely among my cohort – was witty. And when, in the ninth grade, a French teacher accused me of being a “pseudo-sophisticate” I wasn’t insulted (though she had clearly meant to insult me). I knew I was a pseudo-sophisticate.

A 14-year-old closeted virginal gay boy; but I had an arsenal of snappy rejoinders for all occasions, and relatively few mortals realised I’d cadged them from the likes of Myrna Loy, Joan Blondell and Glenda Farrell.

My new book is about some of the movies that gave me those one-liners, taught me what it meant to “put a song over”, saddled me with the mistaken notion that one great song constituted a nightclub act, gave me a working definition of Real Talent by which I continue to live my life, and – in short – made me gay.

Movies That Made Me Gay (Team Angelica Publishing), is available to buy online and at all good book retailers now.