The persecution of trans people by the Nazis was devastating – and it still echoes down the ages

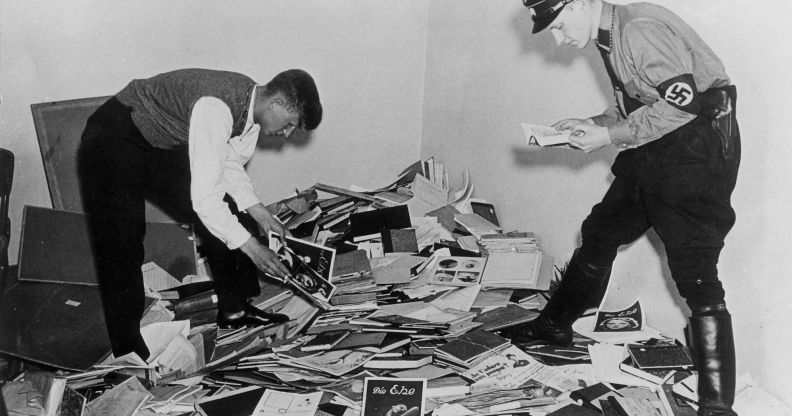

On 6 May 1933, Nazi demonstrators raided and burned books from the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft. The Institute housed important research on trans lives and offered gender-affirming surgeries to the community. (Getty)

During the Weimar Republic – a period in German history following World War One, before the rise of the Nazis – the country was an epicentre for LGBTQ+ people, with movements supporting transgender and gender-non-conforming folks.

That all changed when Adolf Hitler took power in January 1933. An early hint of the wave of deadly discrimination queer and trans people would face soon followed.

On 6 May, fanatical Nazi students raided the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft, roughly translated as the Institute of Sexology. Tens of thousands of books, papers and research were taken from shelves and burned.

The institute, headed by Magnus Hirschfeld, was an academic foundation devoted to sexological research and studies on the experiences of transgender people. It also offered some of the first modern gender-affirmation surgeries in the world.

Tragically, the institute’s large lists of patients’ names and addresses were seized during the raid and, it’s believed, were instrumental in the arrest thousands of people – and the subsequent deportations to concentration camps – in the months and years that followed.

Hirschfeld himself escaped because he was on a talking tour of Europe. He never returned to Germany and died in France in 1935.

The Nazis continued to target transgender and gender-non-conforming people, alongside other groups they believed threatened their ideology and rule. In the terrifying years that followed, transgender people would be sent to the camps and other centres of death, alongside Jews, the disabled, cisgender queer people, members of the Roma and Sinti communities and other groups considered degenerate or of no use.

The Nazis exploited existing laws – including the notorious paragraph 175, a part of the German criminal code that made homosexuality illegal – to attack transgender and queer men and women. In 2023, for the first time, the German parliament focused its memorial day events on those targeted by the Nazis because of their gender identity and sexual orientation.

Historian Dr Bodie A Ashton is among those researching how Hitler deported transgender people to concentration camps and wiped out once-vibrant support structures.

He tells PinkNews that the Weimar Republic was a “moment of major transition and rupture for German society”. It was a time when “everything that had existed beforehand is called into question” in the wake of World War I.

“We have, for example, what could be considered the first gay rights movement in Germany, founded in the last decade of the 19th century: the Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee, the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, that’s helmed by sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld,” Ashton says.

At the start of the 20th century, Hirschfeld, a cisgender gay man, began doing scientific research into die transvestiten, which “maps imperfectly but roughly on to what we would now call transgender” identities, Ashton adds.

Hirschfeld opened the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft in 1919, and began building a library of work around the experiences of trans people.

“He looked upon things to do with his so-called transvestiten and, recognising that they have a very difficult position in society because gay sex is illegal [under] paragraph 175, he’s specifically looking at people who were assigned male at birth.

“They have great difficulty in presenting as the gender they want to present or identify with more closely in public because of the fact that they’ll be read by the police as being gay men.”

This was dangerous because transgender people could be seen by the police as falling foul of paragraph 175, who assumed that a transgender woman was “soliciting for gay sex”.

However, Hirschfeld took evidence to the Berlin police showing that trans people have an “inner drive to present” as their authentic self and aren’t “out there soliciting for sex”.

In partnership with the police, he created transvestitenschein, a type of state licence for trans people.

Dr Jake Newsome, a scholar and author on German and American LGBTQ+ history, describes these documents as “essentially gender-affirming identification cards that trans people could carry [to] acknowledge their true identity”.

It was, he says, unprecedented for the time. “Some new research is happening to try to figure out how many of these certificates were issued, to whom and what they cost”.

Magnus Hirschfeld stands as an important figure in advancing knowledge and understanding of the trans community, but personal views complicated his place in history. He held, what we know today as racist and sexist views and was a proponent of eugenics.

For Ashton, it’s important to remember that Hirschfeld “was a human being in a particular time and context”. He had “positions or interests that would horrify us now”, but it’s “completely to be expected for the time, the person and the society which he was in”.

Historians uncovered the stories of a number of transgender people, including performer Liddy Bacroff, Gerd R, cafe owner Toni Simon, Fritz Kitzing and carpenter Gerd Katter who all suffered under the 12-year Third Reich.

Dr Newsome says it’s important to remember the names of these transgender individuals because it restores their humanity after the Nazis “reduced their entire complex, dynamic personhood down to a singular facet of their lives that the regime considered to be deviant or criminal”.

On a larger scale, remembering the persecution of trans people between 1933 and 1945 is crucial in understanding that the “attacks, lies and stereotypes we are experiencing today aren’t new”, he adds.

“Some of these things, they come from an almost copy-and-paste playbook from the extreme far-right. A lot of the arguments the right-wing in the US today are using are almost play-by-play the same that the Nazi party used in Germany in the 1930s: for example, this idea that trans people are a threat to youth, that they’re going to corrupt young people or try to tempt them into a lifestyle.

“Knowing this history also offers a historical warning that progress is fragile. We look at the Weimar Republic, we look at this vibrant culture queer people built for themselves, and it was destroyed and driven back underground within a matter of weeks.

“To me, that’s a warning that just because marginalised communities have won rights today doesn’t mean they can’t be taken away.”