The Stonewall Uprising: How a group of trans women of colour, butch lesbians and queer youths sparked the LGBT+ rights movement

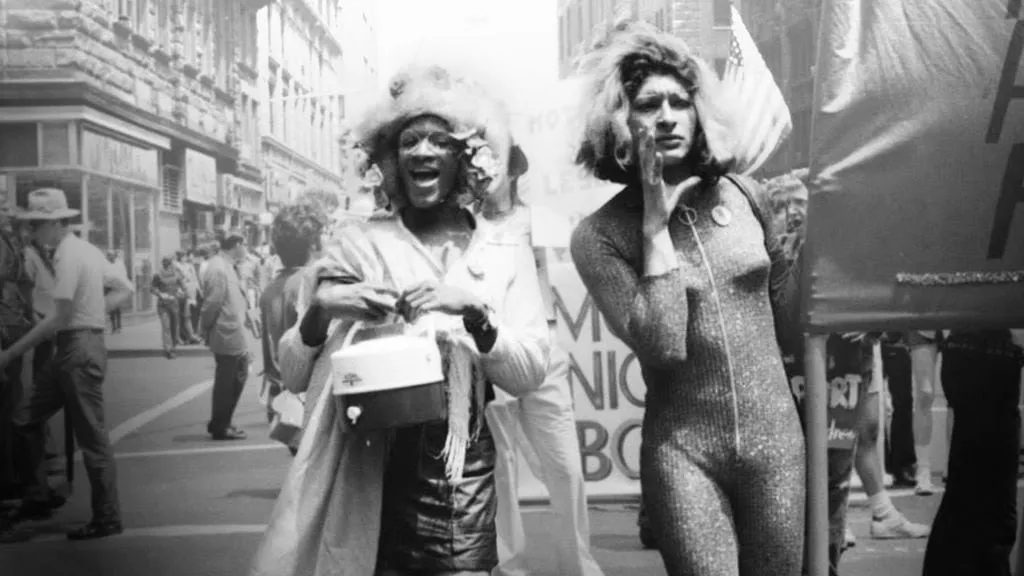

Marsha P Johnson and Sylvia Rivera making transgender history at the Stonewall riots. (Netflix)

Pride month 2020 is a time for queer celebration, visibility, and above all else, protest.

Though Pride month might have become synonymous with parades, festivals and revelry, it is at its heart an opportunity to remember the LGBT+ trailblazers who came before us, and to continue their work fighting oppression.

This year, Pride 2020, will look a little different.

With coronavirus challenging the queer community in unique ways, parades will be replaced by virtual gatherings, protests by online activism efforts. But now more than ever, it is vital we remember our history, and continue to oppose hate wherever we see it.

When is Pride month 2020?

June is recognised around the world as LGBT+ Pride month, dating back to the Stonewall uprising (or Stonewall riots) of June 28, 1969.

That night, approximately 200 queer folk, among them trans women, lesbians, gay men, drag queens and queer youths, had gathered in the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, New York City.

At the time, police in New York were cracking down on the city’s queer venues. Many were unable to obtain liquor licenses, meaning the Mafia had stepped in to run many, including the Stonewall.

It was commonplace for officers to raid bars and clubs on the pretence of checking for licensing violations and “lewd” offences – such as two people of the same gender dancing together.

What actually happened on the majority of occasions was that police would intimidate, assault and detain queer people, subjecting trans women to humiliating gender inspections before arresting them, and would demand payoffs from bar owners – a practice known as payola – in exchange for turning a blind eye and not leaking the names of well-known customers to the press.

“They wanted to harass you know, the queens, the dykes,” Mark Segal, who was 18 at the time of the Stonewall uprising, told PinkNews.

Pride 2020 marks 51 years since the Stonewall Uprising.

Bars would usually receive a tip-off ahead of such raids. But in the early hours of June 28, the hottest night of the summer, six officers walked into the Stonewall Inn with no such notice.

As the music screeched to a halt, the once-darkened dance floor lit up, revealing a number of undercover officers already present. Customers were ordered to flash their IDs and leave.

At first, “there was laughing and joking”, Robert Bryan, who was 23 at the time, told the BBC.

The queer community was used to such raids, and to being mistreated at the hands of police. But as officers accosted and harassed bar-goers, the mood turned.

There are varying account of what happened that night, but most say that the uprising was triggered when police tried to shove Storme DeLarverie, a butch lesbian, into a car while beating her with a stick.

DeLarverie fought back, and the scene exploded.

Marsha P Johnson (left) and Sylvia Rivera (right). (Netflix)

Soon the crowd was throwing stones, coins and bottles at officers, who retreated into the bar as the protest steadily grew in size.

They barricaded themselves, but protestors eventually broke into the Stonewall Inn and set the bartop on fire with lighter fluid.

“It was just this emotional, adrenaline-crazed moment, completely irrational,” Bryan said.

“God knows I would never have kicked a policeman if I were alone. We were finally fighting back and it was exhilarating.”

Segal added: “It’s probably the happiest riot there ever was and the reason it was happy is very simple.

“The police represented two thousand years of oppression, everything that each and every one of us had ever gone through.”

Tactical riot officers eventually broke up the protest, arresting at least 13 demonstrators. At least one officer was treated in hospital.

What happened next?

Marsha P Johnson was among those who joined in that first night of protest. While she is often credited with “throwing the first brick”, she openly admitted that she only arrived at the scene after it had gotten underway.

Sylvia Rivera is another trans woman of colour who was there on the first night, and like Johnson, became part of the vanguard that kickstarted the LGBT+ rights movement.

The uprising continued the following evening. Crowds assembled at the Stonewall Inn, chanting “gay power” and “we shall overcome”, with police again battering the crowd and setting off tear gas.

These confrontations continued for a number of nights, with the bar becoming the epicentre of the nascent LGBT+ rights movement as large-scale riots and police brutality were replaced by less explosive demonstrations – in essence, the first Pride gatherings. Quickly, the Gay Liberation Front and the Gay Activists Alliance were set up to organise activism.

What happened at Stonewall was the beginning of a long fight that continues to this day. A year after police had raided the bar, thousands gathered in Greenwich Village to march more than 50 blocks to Central Park. It was the first Pride march, and slowly the act was replicated across the world.

Why do we still celebrate LGBT+ Pride?

Now, major cities in LGBT-friendly nations host major Pride month events that draw thousands – for Pride 2020, these have largely been replaced by virtual events and gatherings.

These events are often described as celebrations moreso than protests, but that’s not to say that the fight for LGBT+ rights is over.

There are still many nations where it is illegal to have same-sex relations, with the simple crime of being gay punishable by prison, or in some cases, death.

Moreover, trans people also continue to find themselves under attack from governments that seek to strip away their rights, and from transphobes who threaten them with harassment, violence, and all too often, death.

Even in supposedly liberal countries such as the US and the UK, trans rights are being gutted before our very eyes. It’s for these reasons that Pride is vital, and even at a time where nothing feels certain, must continue.