Raunchy gay magazine, full of hunky men, hid in plain sight on newsagent shelves in 1950s UK

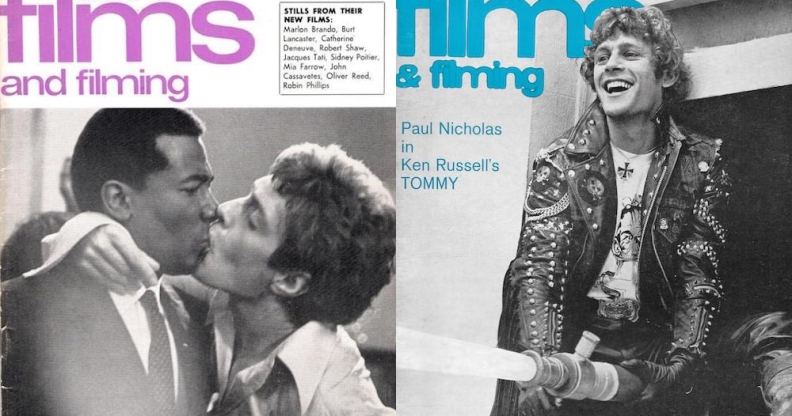

Films and Filming covers from 1968 and 1974. (Films and Filming)

One of Britain’s first-ever gay magazines, full of topless hunky men, hid in plain sight on the shelves of newsagents in the 1950s, almost two decades before the decriminalisation of homosexuality.

Films and Filming was, as the name suggests, a film magazine, which was internationally respected. But for those who knew what they were looking for, it was so much more.

Launched in 1953, it made its debut at a time when gay men were severely persecuted in the UK; that same year saw the journalist and later LGBT+ rights campaigner Peter Wildeblood, along with Lord Montagu of Beaulieu and Michael Pitt-Rivers, tried and convicted of gross indecency.

A year previously, Alan Turing had been convicted and was chemically castrated in order to avoid being jailed. By the end of 1954, in England and Wales, there were 1,069 gay men in prison for homosexuality.

To say that launching a gay magazine in this climate would have been enormously risky would be an understatement, so publisher Philip Dosse, described by one of his former employees as “proud, eccentric, gay, secretive [and] volatile”, had to be cautious.

According to a paper by Dr Justin Bengry, director of the Goldsmiths Centre for Queer History, from its very first issue the magazine “subtly included articles and images, erotically charged commercial advertisements and same-sex contact ads that established its queer leanings”.

Films and Filming included profiles of actors who were at the time rumoured to be gay, like Rock Hudson and Dirk Bogarde, as well as photos of them in various states of undress.

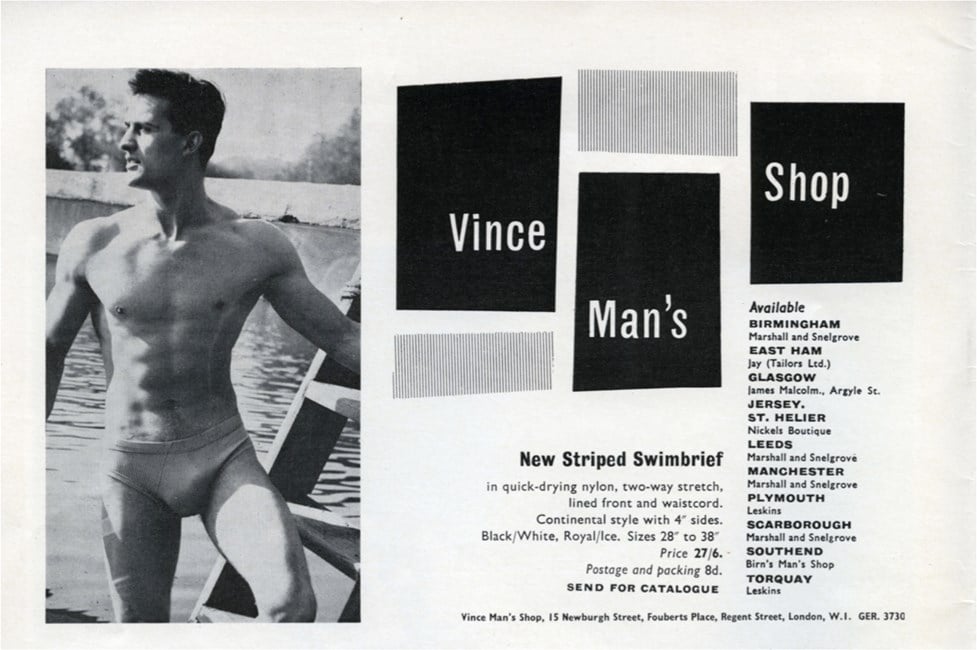

Advertisements were chosen for their highly sexual images of men, and the magazine also became renowned for its classified section, which featured contact ads for men looking for same-sex partners. Of course, the requests weren’t explicit, and mostly featured ads from “bachelors” who were looking for “friends” with interests like “wrestling” or “physique”.

Advert for Vince Man’s Shop in the July 1959 issue of Films and Filming. (Films and Filming)

According to Bengry, as well as providing one of the only avenues for queer men to connect with each other, men also used the ads to trade homoerotic photos and films, making it “a veritable queer marketplace”.

“Taken together, these elements all reinforced, for many readers, that despite its respectable credentials and mainstream accessibility, Films and Filming was, in fact, queer,” wrote Bengry.

https://twitter.com/FilmsFilming/status/1458700269345116164

Films and Filming allowed gay men to look at homoerotica ‘on the tube or at the office’

Films and Filming‘s status as a respected film magazine put it in the perfect position to hide in plain sight, and it was widely available in newsagents and bookshops throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

The magazine’s third editor, Robin Bean, described its appeal for the queer community: “Gay men who were in the closet, especially those who still lived at home with their parents or were married, could openly sit on the tube or a bus or in school or the office and be viewed reading the magazine without fear of anyone suspecting they were gay.”

However Bean, who became editor in 1968, would also oversee the magazine’s downfall.

Under Bean’s leadership, the film writing suffered and it became better known for hunky men, even using full-frontal nudity on the cover in the 1970s.

This change of tack meant that it could no longer straddle the film world and the queer world, which was exactly what had made it a safe space for gay men as well as financially successful.

Film buffs no longer wanted to read it, porn magazines were flourishing with much more explicit content that Films and Filming could offer, and those who wanted to remain in the closet could no longer read it in public.

Publisher Philip Dosse’s company Hansom Books suffered significantly, and finally collapsed in 1980, after which Dosse died by suicide.

The magazine was briefly resurrected in the 1980s, but those who had loved it in its heyday no longer needed to use classifieds to make connections with their community.

Nevertheless, the its “widespread accessibility in a time of repression” made Films and Filming a lifeline for queer men in pre-decriminalisation Britain.

As Bengry wrote: “It offered a nationally, and even internationally, distributed opportunity for men to find public discussions of homosexuality, suggestive commentary and homoerotic imagery from contemporary films; it even opened up a space for them to find each other.”