World AIDS Vaccine Day: A vaccine would save countless lives – but it wouldn’t be a silver bullet

The fight against HIV has been transformed by medical breakthroughs such as PrEP.(Getty/Envato/PinkNews)

It’s been more than 40 years since the virus that eventually became known as HIV was first identified – yet there’s still no vaccine.

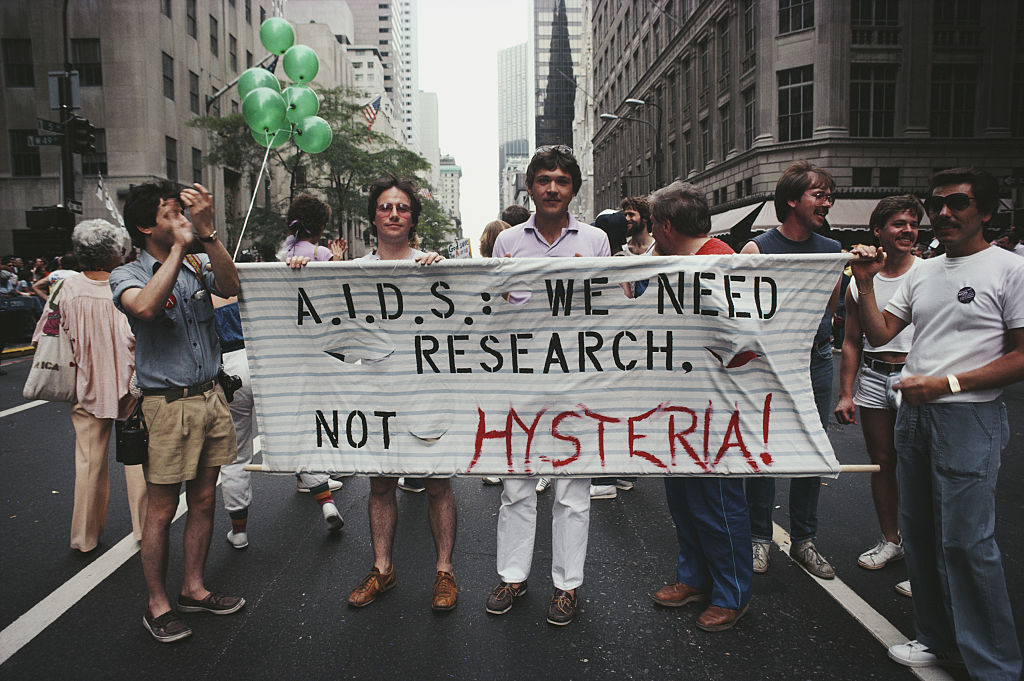

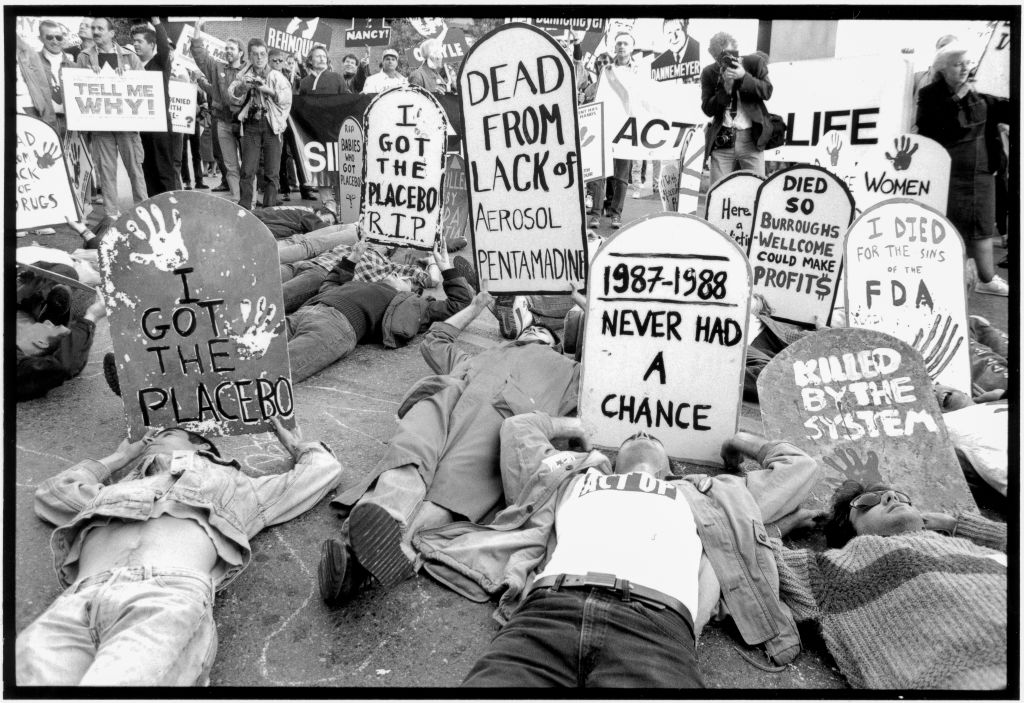

The AIDS epidemic decimated queer communities across the world following its emergence in the early 1980s and it continues to hold millions of people in its grasp to this day. An estimated 38.4 million people were living with HIV in 2021, according to UNAIDS. Possibly as many as 860,000 people worldwide died from AIDS-related illnesses that same year.

Much has changed since the early days of the epidemic. Thanks to antiretroviral treatment, people living with HIV can now live long, healthy lives – as long as they’re able to access medications – and Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP), when taken daily, is highly effective at stopping people contracting the virus.

Those changes have been radical and revolutionary – but to many, the continued lack of a vaccine is a sore subject.

Every few months, another news story does the rounds, detailing how the latest HIV vaccine has been abandoned after it failed at clinical trial stage. In January, the only vaccine in the latter stages of testing proved to be just another dead end, setting progress back by up to five years.

It’s been a long road to finding a vaccine – and there’s no end in sight, says Matthew Hodson, the executive director of aidsmap.

“I would say we’re not in a good place at the moment,” Hodson tells PinkNews. He points to recent setbacks with the Mosaico trial among other high-profile failures. Other vaccines are in development, but they’re a long way off completion, he adds.

On January 18, the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson, together with a consortium of global partners, announced that an independent monitoring board concluded that, while there were no safety issues, the regimen was not effective in preventing HIV infection.

“We’re probably talking many years, possibly more than a decade before anything would be available, and that’s only if everything goes well – which our experience tells us isn’t always the case,” Hodson continues.

“I’ve been living with diagnosed HIV for 25 years and throughout that whole time I’ve heard people talk about a vaccine that’s just around the corner, but we still haven’t turned that corner.”

Because COVID-19 vaccines were developed so quickly, there was some renewed faith that an HIV treatment could be next, but those hopes have so far been dashed.

Part of the problem is that HIV is a more complex virus than COVID-19, Hodson says, which makes it more difficult to develop an effective vaccine. There’s also the fact that it’s harder to gauge efficacy with an HIV vaccine.

With COVID-19, the virus was proliferating rapidly, spreading from person to person. It wasn’t difficult to gauge the effects of widespread vaccination as the number of people being hospitalised and dying began to decrease.

HIV is a very different beast – it’s much less common and the gap between transmission and diagnosis is significantly wider. That makes it trickier for researchers to figure out the efficacy of potential vaccines.

HIV vaccine wouldn’t be 100 per cent effective

While we don’t have a vaccine, a combination of antiretroviral treatment and PrEP has made it much easier to prevent transmission.

So, given how effective those tools are, how important is it that we find a vaccine?

If a vaccine was approved, it almost certainly wouldn’t be the silver bullet. It’s unlikely that it would be 100 per cent effective and people might require boosters throughout their lives. That’s why Hodson believes the fight for a vaccine should be seen as only one part of the battle.

“It’s a personal view, but I feel that when we have really effective methods of preventing transmission of HIV, we should focus our efforts on ensuring everyone who would benefit from access to PrEP can access it, and that everyone who lives with HIV has access to the treatment.”

He adds: “The field of HIV prevention has moved on considerably since we first started talking about vaccination. We have PrEP which works very effectively. Injectable PrEP is even more manageable and already we have injectable PrEP which will last for a couple of months.

“Done the line, we’re hopeful we will have injectable PrEP that will last six months. When we look at those prevention options, they’re kind of similar to what we might hope for from a vaccine.”

Hodson believes it’s more important that our present focus is on ensuring everyone who needs it can access antiretroviral treatment and PrEP.

Millions of people across the world are currently unable to do that. The same barriers that prevent people accessing treatment today would also be likely to hinder a vaccine rollout if one was approved.

The most obvious barrier in some parts of the world is cost, but there is also the fear of stigma, long waiting times at clinics and even worries about just how much protection medicines such as PrEP actually provide and the perceived, or real, side effects.

“There are still almost one in four people living with HIV globally who do not have access to effective treatment – a scar on our collective conscience,” Hodson says.

“If I had to allocate my resources, I would allocate it towards ensuring that everyone has access to testing and treatment because that not only saves lives, but it will also prevent – or halt – the ongoing epidemic.

“We’ve got something that works and saves lives, so let’s make sure everyone has access to it.”