Men like Russell Brand have been given a free pass by institutional inaction for far too long

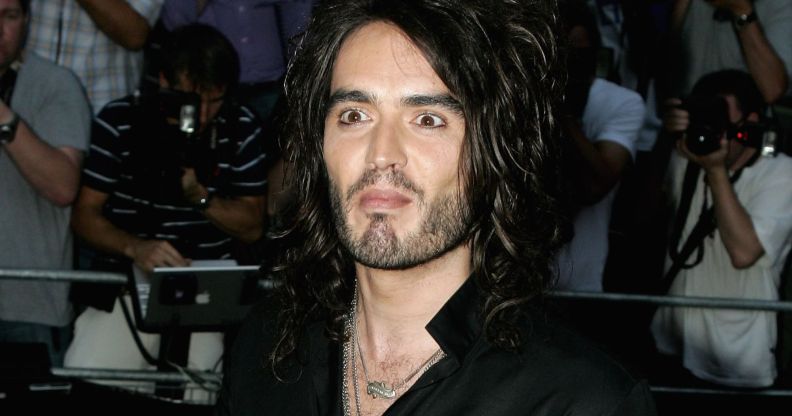

Russell Brand during a 2006 press event. (Getty)

In light of the serious sexual assault and rape allegations against Russell Brand, Amelia Hansford argues that his sexist brand of comedy was always a red flag.

During a live BBC Radio 2 interview in 2007, with millions of listeners, comedian Russell Brand offered his personal assistant, naked, to Jimmy Savile.

The uncomfortable moment between the former Big Brother’s Big Mouth host and Savile, whose death in 2011 opened the floodgates in exposing decades of sexual abuse, pedophilia and necrophilia, was a small insight into Brand’s sexually promiscuous, edgy jokes at the expense of women. In fact, the comedian-turned-actor-turned-YouTube-guru has arguably built his career on bragging about his sexual prowess and objectifying women in the process.

What’s even worse than hearing two famous, influential men banter over making their female co-workers give massages on demand, is the fact that such serious allegations of sexual abuse had to surface for institutions to take meaningful action against Brand.

Since the joint investigation between The Times, The Sunday Times and Channel 4’s Dispatches revealed allegations of sexual assault, rape and emotional abuse against Brand, both Channel 4 and the BBC, who employed the comedian for years, sprang into action with internal investigations. Brand vehemently denies the allegations, saying that he was sexually promiscuous but his sexual encounters were always consensual.

But Brand’s employers should’ve moved sooner – because his inappropriate and wildly sexist behaviour was already evident, on air, for the world to see.

Why not when, working as a Radio 2 host, he harassed newsreader Andrea Simmons live on air, saying he wanted to “unleash hell on [her] thighs”, despite Simmons making complaints against him at the time?

Why not while he was the host of Big Brother’s Big Mouth, publicly grinding against women with his trousers down?

Sure, Brand – and Jonathan Ross – were suspended over the ‘Sachsgate’ incident, where the pair left lewd messages on actor Andrew Sachs’ answerphone about Brand’s relationship with his granddaughter, Georgina Baillie, on BBC Radio 2.

But it barely touched Brand, even though he resigned from the BBC following a public outcry, winning the British Comedy Award for Best Live Standup Performer just over a month later, and dedicating it to Ross.

The reality is that Brand’s flavour of comedy stems from the media landscape of the early 2000s, when tabloid newspapers revelled in printing sexist, homophobic filth, counted down to when female child stars would be ‘legal’ and shamed women in the public eye for partying while celebrating their male counterparts for the same behaviour, and reality TV pushed harmful gender stereotypes with caricatured portrayals of both men and women.

But simply excusing Brand’s behaviour as a product of its time isn’t good enough, because, in many ways, this era is still alive and kicking.

Look at the recent Luis Rubiales controversy, where the former president of the Royal Spanish Football Federation (RFEF) kissed Spain captain and world champion Jenni Hermoso on the lips without her consent, completely shattering what should have been a momentous celebration for women’s football.

Rubiales’ reluctance to take responsibility for his actions, and the RFEF’s remarkable ability to churn out excuses for its president, sparked an outcry for justice so widespread that the calls of feminist protestors marching across the streets could practically be heard from the Iberian shores.

It took weeks of constant calls for Rubiales to resign, the entire Spanish football team boycotting future games, Hermoso having to repeat how vulnerable she felt during the incident, and a legal investigation, before steps were taken to suspend the president.

In the end, it wasn’t even the RFEF that made the decision. FIFA was forced to step in to clean up the damage.

In a post-MeToo era, institutions are prepared to laud how much easier it has become for women to speak up about sexual assault and harassment, rape and violence. But when push comes to shove, those same institutions will fall back on excuse after excuse until they are finally forced to act.

At the time of writing, both Brand and Rubiales have faced some consequences for allegations against them: Brand’s agent has dropped him, his YouTube channel has been demonetised and charities – including women’s and children’s charity Trevi – have cut ties.

But where were these executives bringing down the institutional hammer when Brand was bantering on stage about wanting to make women choke on his genitals, to see mascara run from their eyes? What kind of a charity ambassador pretends to masturbate after asking a female chat show guest what bra they are wearing?

It’s difficult to know why Brand’s retrospectively abhorrent, misogynistic showbiz career was enabled for so long by broadcasting giants. Why out of the billions of people on this planet, a self-aggrandising, sexist, pseudo-pirate caricature was allowed to sully millions of television screens for decades without the slightest bit of scrutiny reaching beyond a suspension here and a fine there?

As one of Brand’s accusers told the BBC of his alleged behaviour: “It’s the biggest open secret going – you don’t have to be an investigative journalist to have conversations with somebody who has an awful experience with him or somebody knows something.”

Whatever the reason, we’re running out of excuses for why men like Russell Brand are given a free pass until the last possible minute.

Rape Crisis England and Wales works towards the elimination of sexual violence. If you’ve been affected by the issues raised in this story, you can access more information on their website or by calling the National Rape Crisis Helpline on 0808 802 9999. Rape Crisis Scotland’s helpline number is 08088 01 03 02.

Readers in the US are encouraged to contact RAINN, or the National Sexual Assault Hotline on 800-656-4673.

How did this story make you feel?