LGBTQ+ elders share important lessons they wish they learned sooner: ‘We deserve good things’

For older members of the LGBTQ+ community, the fight for their rights is in no way over. (PinkNews/Supplied)

Getting older might not sound like much of an achievement – but for LGBTQ+ people, it’s almost unthinkable.

In conversations with PinkNews, queer elders who spent decades hiding from prejudiced eyes have recalled tiring yet rousing lives spent battling for their rights – and for the right to grow old.

When Tanya Walker was just six-years-old, she realised she was going to spend her life fighting.

From the first grade in 1968, she was relentlessly bullied at her school in South Plainfield, New Jersey.

“I had to defend myself,” she told PinkNews. “My dad told me that I would change as a little kid. I thought I was gonna change, become what he wanted me to be, not who I was.”

As she went to school each day, many of what would become milestones of LGBTQ+ history passed her by. She didn’t even realise the Stonewall Uprising happened in 1969.

“I heard bits and pieces of it,” she said, from an uncle, a police officer in Greenwich Village. “I was surrounded by cis, hetero folks.”

Walker thought enrolling in the army would be a fresh start for her. As a 17-year-old US Armed Forces combat engineer, she stepped out of a cattle trailer in New Jersey and lined up alongside 300 men as a drill sergeant took to the stand.

“I would like to welcome the first girl in the army,” he barked, “private Walker.”

“And that’s me,” Walker said four decades later. “Everybody looked at me and they started to laugh. For my whole army career, they called me a f****t. I was tortured.”

“In those days, it was rough, and it’s still rough. Things have got a teeny bit better, but people haven’t changed their views about us. They used to have the police [involved] – trans women couldn’t even wear more than two articles of women’s clothing as they’d get arrested for ‘impersonating’ a woman. They really made our lives a living hell.”

According to GLAAD, the average life expectancy of trans women of colour is 35. For a cis woman, it is 78.

Walker, a Black trans woman, is 58-years-old.

Many queer elders like Walker are still having to fight. And their struggles continue well into their twilight years, according to Christina DaCosta, senior communications director for SAGE, which advocates for older queer people.

“A few of the cornerstones for successful ageing include health and well-being, economic security, and social connections,” she said. “But these are the very areas in which LGBTQ+ elders face significant barriers.”

With a lifetime spent hiding, of not being able to marry the one they love, of not being able to serve in the military or hold down a job, three in 10 will “re-closet” themselves, DaCosta added.

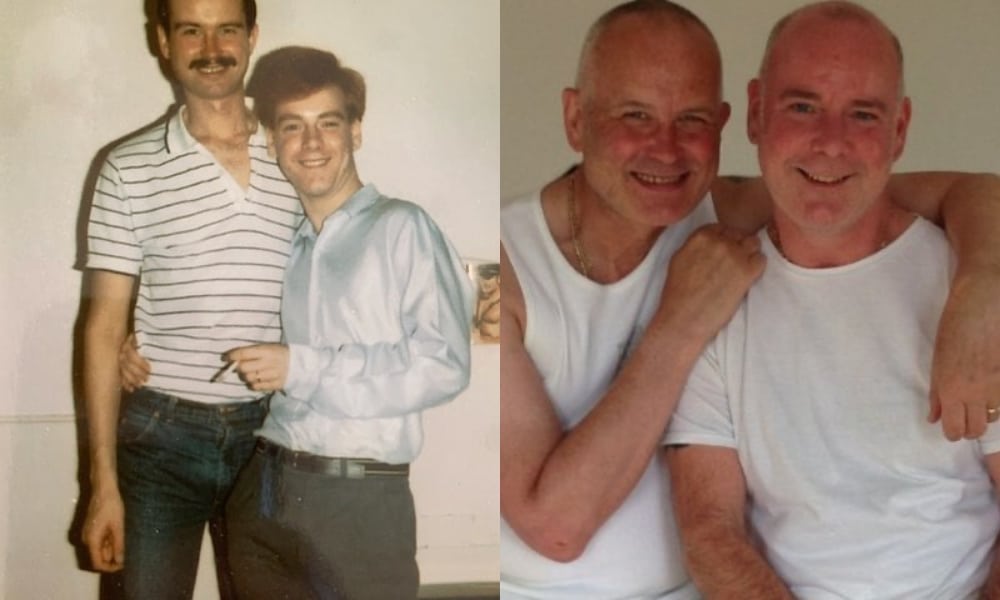

Roger, a 64-year-old former disc jockey from Huddersfield, England, did just that when he started working at clothing and home retailer, TK Maxx, seven years ago. He only came out as gay to his colleagues in 2021.

It was his choice to re-closet himself, he stressed, having felt stung by his experiences of coming out at his last job in a warehouse where other workers made snide remarks about his sexuality.

“I don’t think being open about it helps,” he said. “I think it hinders us even more. You almost have to live two lives.”

Roger is used to doing this. Even after Britain partially decriminalised homosexuality, he still had to listen out for the police banging on the doors of queer nightclubs such as Huddersfield’s Gemini where he danced in the 1970s.

“In the end, that became Gemini’s downfall because instead of getting less frequent because times had changed, the police raids became even more common,” he said. “The Gemini had at least two raids every month.

“You rang the doorbell and someone looked out of an office window above the door and, if they recognised you, they’d press the buzzer and let you in. If they didn’t, they’d ask you questions to find out if you were here to make trouble.”

He now lives in Ireland with his partner, Martin, and their three dogs and two cats. It’s a long way away from the Gemini.

This new way of living – being open – is still a strange one for him. “But if I had my life all over again, I wouldn’t do it any other way,” he said.

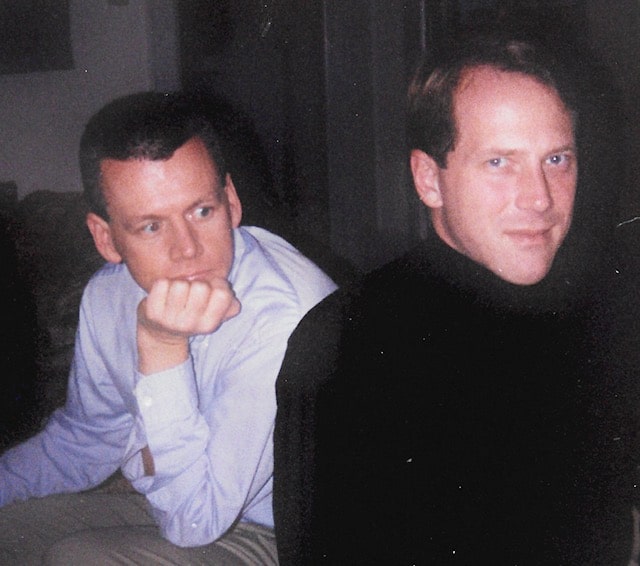

Like Roger, Tony Openshaw, 66, knows that shame can be hard to shake off when you’ve lived it for most of your life.

He was a 12-year-old kid in Bolton in north west England when homosexuality was partially decriminalised in 1967. Though he wasn’t a criminal in the eyes of the law anymore, his family saw otherwise.

“My parents sent me to a psychiatrist,” Openshaw said. “I had one appointment for one hour and he decided I wasn’t gay. He told my parents, which made it even harder to come out – they thought I was influenced by the pop music of the time, David Bowie, that sort of thing.”

“As a youngster thrown out of the house, I had no alternative than to be an activist,” Openshaw added. “There was nothing else to do. We couldn’t get married, we couldn’t join the military.”

Section 28, banning the “promotion” of LGBTQ+ identities by schools and local authorities, was passed by prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s government in 1988.

Openshaw had to do something. So on 20 February, 1988, Tony gave a speech against Section 28 alongside actors Ian McKellen and Michael Cashman, in one of the largest LGBTQ+ protests ever held in Britain.

“Even in our lifetime, so many things have changed. The age of consent was reduced to 18, and then we got equality at 16,” Openshaw said. “Gays could have civil partnerships and then marriage – so many rights have happened, and so many younger people take these for granted.

“It is such a short period of time,” he continued, reflecting on his 71-year-old partner Norman only coming out as gay two years ago.

“He’s lived a long, straight life. For him to realise his sexuality now and for us to come together is wonderful. But I’ve lost out on things, like family, and relationships.”

To queer elders, the AIDS epidemic was a time of loss and bravery

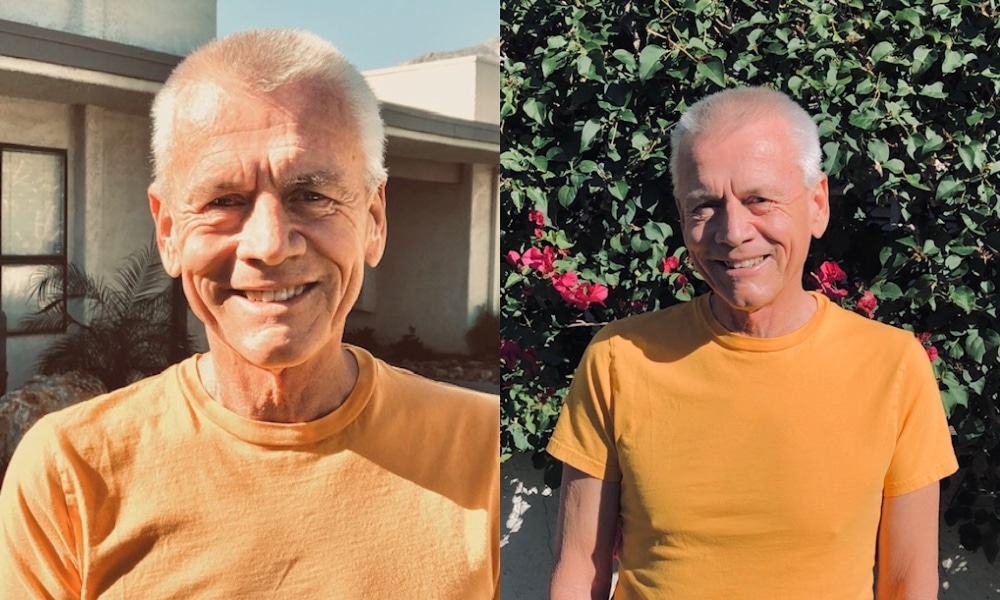

Many of the queer elders spoke of loss almost unflinchingly, as if it’s a given. None more so than James Lance, a 66-year-old gay man living in Palm Springs, California.

Lance left the Texas farm he grew up on in the 1950s (his Christian fundamentalist family thought he had been possessed by a demon) thinking he knew exactly who he was. Then he saw some gay pornography.

“It was like a light bulb going off,” Lance said, “I finally realised who I was.”

Following years spent as a “party boy”, Lance met Ronald in the 1970s. They enjoyed two years full of love before Ronald died of complications caused by AIDS.

At the time, Lance had no clue what was going on – “there was no name for it and no testing for it,” he said.

The AIDS crisis had only just begun, casting a shadow on the lives of LGBTQ+ folk for decades and claiming unbearable numbers. By 1988, the disease ranked 15th among the leading causes of death, according to the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention.

But Lance didn’t know this yet, all he knew was grief. “I was 29 when he died and it was just an unbelievable nightmare. He was in a hospital and the doctors wouldn’t touch him, and he died a horrific death, ostracised and shoved to the side.”

Lance soon came to know he himself was living with HIV: “I was walking around knowing that, at any time, that could be me as well. Any kind of cough or bruise, I knew it was the beginning of the end. The ’80s were a dark time for me because we had Ronald Reagan as president – his administration just didn’t care.”

So he joined the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, better known as ACT-UP.

“ACT-UP gave me a way to focus my anger and fear and all these emotions, to yell at people, lay down in the middle of the street,” he said. During one demonstration, Lance and others stormed the Texas Capitol.

Some stood in the legislature mezzanine to remind state lawmakers they existed. Others, including Lance, stood outside drenched in fake blood and performed street theatre. He didn’t mind the screwed-up faces of onlookers walking past.

He was jailed twice.

“It was nice to see that I could freak people out the way they were freaking me out, you know?” Lance said. “To see the fear in those bigots having this brought to their attention, what they’re doing to my friends.”

Lance fought not just for the lives lost but for the lives only just beginning in the 1980s and beyond.

“I thought it was so important for younger LGBTQ+ people to never have to go through what I went through,” he said. “I never thought I would make it to 66. I’ve nearly died three times from AIDS-related complications, but now I’ve been undetectable for decades, it’s miraculous.

“We are the strongest, most powerful, most creative people and we deserve good things,” Lance said, choking up, his head in his hands. “I will always remember my friends that aren’t here.”

“I’ve seen how it can all be taken away, the progress we’ve made,” he added. “And I will, until my last breath, fight for our community.”

How did this story make you feel?