How Ed Buck got away with deadly abuse of young Black men for years: ‘They were objects to him’

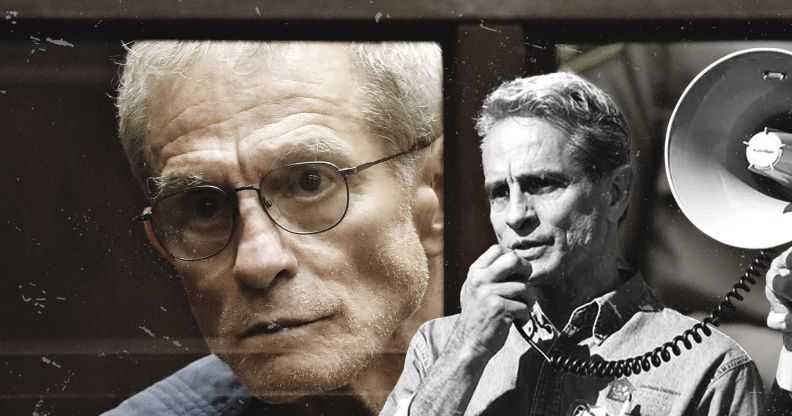

Ed Buck pictured at his trial and in a historic image. (Getty/Ed Buck Facebook/PinkNews)

On 27 July 2017, a young Black man called Gemmel Moore was found dead in the apartment of Ed Buck, a prominent Democratic donor and businessman.

Reports had been circulating for some time that Ed Buck had a history of bringing Black men to his home where he would inject them with crystal meth – and yet, he evaded arrest until 2019, when another man by the name of Timothy Michael Dean was found dead in his apartment.

Exactly four years after Moore was found dead, Buck was convicted of nine federal charges and was sentenced to 30 years in prison. Today, the question remains: how did Buck get away with his abusive behaviour for so long?

It’s a question journalist Patrick Strudwick is determined to find an answer to. His new Audible podcast series, White Smoke: America’s Chemsex Killer, uncovers how a heady cocktail of power, wealth and structural racism enabled a wealthy white man to abuse Black men without any attention from authorities.

Strudwick first came to the Buck case in the autumn of 2019 when local communities started to raise the alarm about his behaviour.

“What I was hearing over and over again was that people of colour were being exploited, that many in the white gay community weren’t listening or caring, and that Ed Buck wasn’t the only one,” Strudwick tells PinkNews.

In LA, Strudwick started speaking to Black and Latinx men who had been abused by white men in chemsex scenarios – and their stories painted an unnerving picture.

“They told a terrifying story about how racial fetishisation was intertwining with, frankly, slavery dynamics,” Strudwick says.

Buck, with his powerful position and his ability to evade attention, was symbolic of just how deep the problem ran. Strudwick knew he was only scratching the surface. He wanted to go deeper and, above all else, he wanted to figure out how somebody like Buck could behave as he pleased without any consequences.

“Two Black men had been pulled out of his apartment dead within the space of 18 months and he wasn’t even arrested for possession of meth, even though meth was found all over his apartment,” Strudwick says.

“In a country where the prohibition on drugs is pretty hardcore, and where Black people can be thrown in jail for the most minor of offences relating to drugs, he was this rich, white, connected, powerful man who was just roaming free. It opened up so many more questions about what was going on.”

Strudwick assembled a team and they got to work on trying to find answers. What they found was that a complex mix of power, racism and prejudice had created a system where abusers like Buck were allowed to thrive.

In making White Smoke, Strudwick and his team discovered that Buck had tried to manipulate officers who came to his apartment by showing them pictures of himself with powerful figures.

Strudwick also took a cold, hard look at Jackie Lacey, the former Los Angeles district attorney, who has faced condemnation over her failure to take action against Buck sooner. Strudwick believes she was reluctant to bring charges out of fear that the case would fail, potentially jeopardising her chances of re-election.

But above all else, what Strudwick and his team discovered was that Buck had been dealt a good hand in life – and that made him untouchable. As a powerful white man, Buck found himself on the right side of a society that is racist to its core.

“In the case of Ed Buck, what he did was exert total control over very vulnerable men,” Strudwick explains. “He did that in a number of ways – first of all, he sought out men who needed either money or meth or somewhere to stay, so immediately the power imbalance is vast between him and them.”

From the start, Buck’s encounters with his victims were notably racist. He would use racist terms to their faces and, chillingly, he would tell them: “I am the engine master and this is my train.”

Once Buck got vulnerable Black men into his apartment, he would “bully” them into taking meth, Strudwick says. If they refused, he would ask them to leave.

“It was as if he was a film director – he would have these Black men, usually in white underwear, pose for him while he took pictures and while he took videos, and he would direct their every movement for his own gratification. They were objects to him that were under his control.”

Ed Buck case shows how Black people are ‘taken for granted’

Micheal Rice, a co-producer on White Smoke, has a distinct perspective on the Ed Buck case. As a queer Black man, he first learned of allegations against Buck in 2017 when he was making his documentary ParTyboi, which delves into crystal meth addiction in queer communities of colour.

Buck’s behaviour, and the fact he evaded arrest for so long, point to the myriad of ways in which Black people are “taken for granted” in America today, Rice says.

“It’s always been a part of our history, all the way from slavery to reconstruction, to redlining to the civil rights movement. It’s still here today. It may play out in different forms – you see it on the political landscape but then you also may see it within the LGBTQ community because even within the LGBTQ community there is a lot of racism still at play.”

It would be easy to downplay the Buck case as an isolated occurrence, but Rice knows that’s too simple. His actions were part of a larger system where the most vulnerable are tossed aside and where the wealthy and the powerful are held aloft.

Similar power dynamics are at play within the LGBTQ+ community, Rice suggests. “At the top of the LGBTQ community are cis, gay, white men and everyone else falls below that.”

If we want to avoid a repeat of the Ed Buck case, difficult conversations must be had about power, wealth, race and consent – and there must also be an open dialogue about what happens when drugs and sex collide.

“I think we have to be really explicit in saying that sex is OK – that drugs, and I include alcohol in that, are just part of life,” Strudwick says.

“But it would be a terrible disservice to ourselves and our community if we didn’t also talk about the fact that some people harm others within those situations.”

He adds: “I don’t want anyone to feel judged if they’re not harming other people. But I do want people who are being harmed to be able to go to the police, to be able to ring an ambulance, to go to their GP, to talk to their friends, and – if they feel ready – to accuse the person who has harmed them and bring them to justice.

“That’s the only way we can protect ourselves.”

White Smoke: America’s Chemsex Killer is out now on Audible.