Was Napoleon bisexual? Five historical figures experts now believe were LGBTQ+

Joaquin Phoenix as Napoleon in Ridley Scott’s new film. (Apple TV+/Columbia)

With Ridley Scott’s hotly anticipated film Napoleon finally now in cinemas, there’s a renewed focus on the life and legacy of France’s most notable emperor.

Born in 1769, Napoleon Bonaparte came to prominence during the French Revolution, and later became leader of the French Republic.

Napoleon was married twice, to women, but that hasn’t stopped people from speculating about his sexuality. He lived in an era where being openly and outwardly gay or bisexual was impossible – although if you were going to try it, France was probably the right place to be.

In the years since Napoleon’s death, his sexuality has been explored by experts and academics. In 1972, Frank M Richardson studied the evidence in his book Napoleon: Bisexual Emperor.

That book, which is now out of print, explores Bonaparte’s relationships with the likes of Alexander I of Russia. He was apparently charmed by the Russian czar, describing him as “especially handsome, like a hero with all the graces of an amiable Parisian”.

Later, Napoleon wrote to his wife: “If Alexander were a woman, I would make him my mistress.”

We’ll never know exactly what Napoleon really meant. It’s entirely possible he was simply telling his wife that Alexander was malleable, somebody who could be manipulated – or maybe he was trying to communicate an attraction that was, at the time, uncommunicable.

Terms like “bisexual” didn’t exist when Napoleon was alive, which complicates things further. LGBTQ+ people often look back and try to assess whether somebody might have been queer, but it’s essential that when we do, we remember that it’s unlikely people would have thought of themselves in the same terms we do today.

Even so, that doesn’t mean we can’t speculate about historical figures and whether they might have been lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender, if the right language and modes of expression had existed in their life time.

As Napoleon’s sexuality and life once again comes to the fore, we take a look at four other historical figures who have endured endless speculation about their sexuality or gender expression.

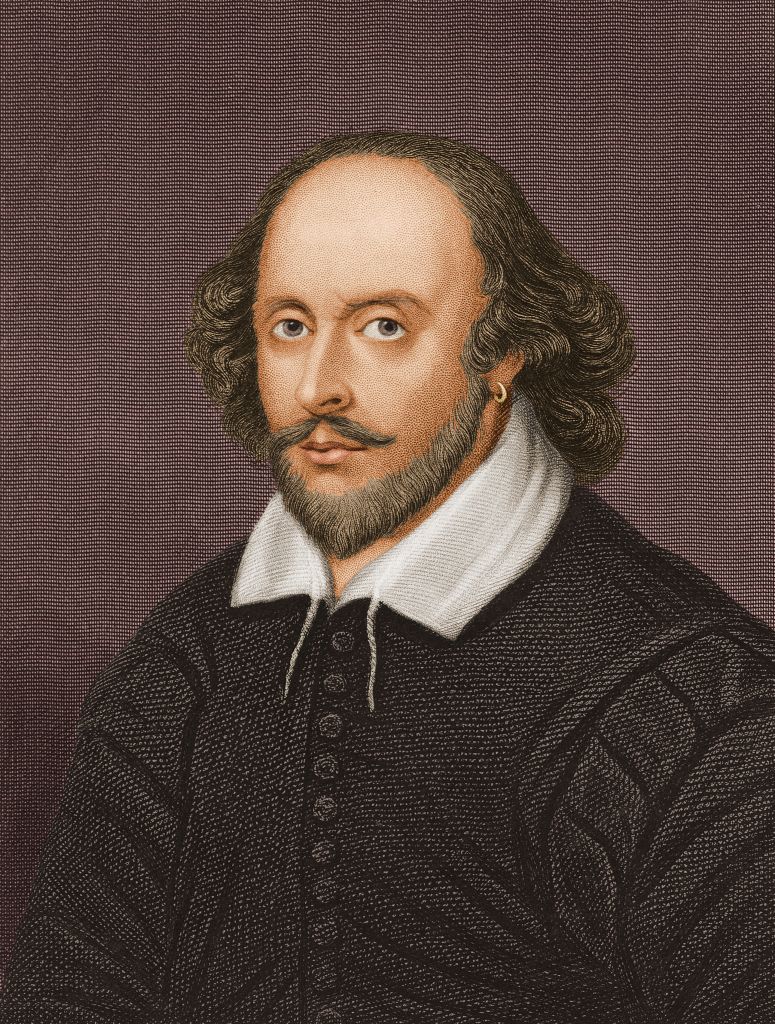

William Shakespeare

More than 400 years after his death, Shakespeare’s sexuality continues to generate massive interest – and that has a lot to do with the large body of work he left behind.

If you’ve ever studied English literature, you’ll probably know that Shakespeare was married to Anne Hathaway – no, not that one.

They tied the knot when the fledgling playwright was just 18 years old, while his wife was 26, and the ceremony was probably rushed because Anne was pregnant. The birth of their first child, Susanna, was born just six months after the wedding.

Shakespeare’s sonnets suggest that he did love Anne in the early years of their marriage, but his affection may have faltered as time went by. He famously left his wife his “second-best bed” in his will, which reads like a sly dig to modern readers.

Later sonnets also reveal some kind of love, longing or attraction to a “fair lord” or “fair youth”. Those poems were dedicated to “Mr WH”, which has led some literary historians to deduce that he was may have been writing about his patrons Henry Wriothesley, the third earl of Southampton, or William Herbert, third earl of Pembroke.

There are repeated references to love throughout those sonnets. In one, Shakespeare wrote that he was “at war with time for love of you”. In another, he describes his male muse as the “master-mistress of my passion”.

Some have argued that The Bard’s sonnets were simply indicative of the way men spoke about their male friends in that era.

Even so, the speculation will probably never die down. The story of Shakespeare’s sexuality is simply too compelling to resist, meaning literary historians will continue to seek further proof.

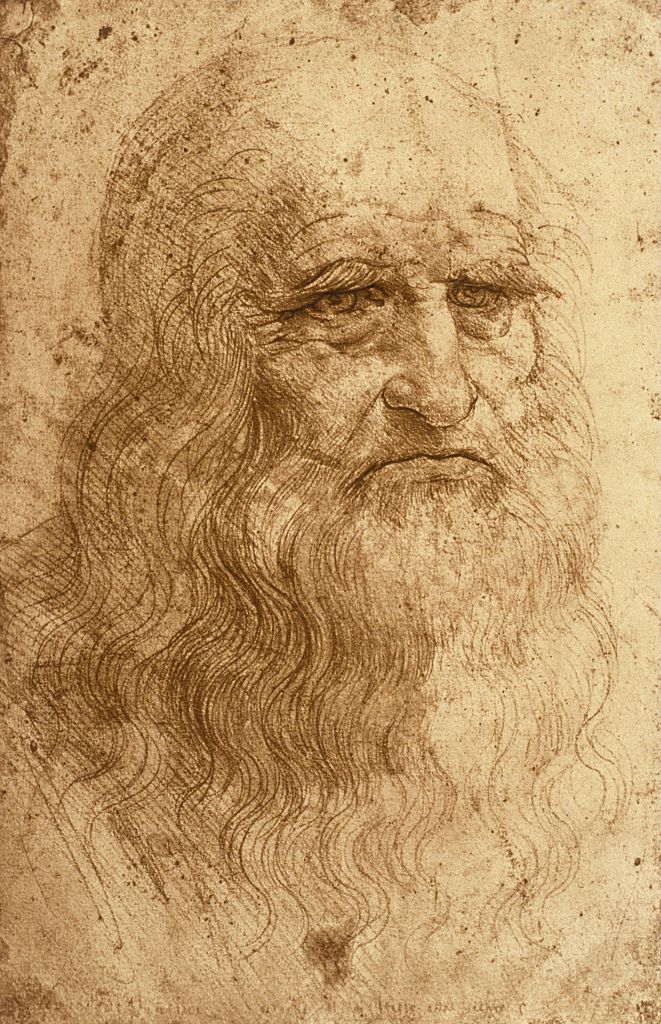

Leonardo da Vinci

Much has been made of Leonardo da Vinci’s sexuality over the years, and with good reason.

At the age of 23, Leonardo was accused of sodomy – which was then a crime – in an unsigned letter. Court records from the time show that four people, including the artist, were denounced for having anal sex with a young male prostitute called Jacopo Saltarelli.

While the charges were dismissed, the very nature of the accusation has led to plenty of speculation from art historians and queer people.

In her book, History of Celibacy, Elizabeth Abbott argued that Leonardo was “probably” a homosexual, but that he was deterred from acting upon his desires because of the trauma left by the sodomy accusations.

What remains unclear is whether Leonardo did or did not have any sexual contact with anybody – male or female – in the years after the case.

Some have suggested that he remained celibate, and his writings seem to point to a disdain for sex more broadly. Others have pointed out that his writings and artistry remained somewhat preoccupied with men.

In Leonardo: The First Scientist, Michael White writes: “There is little doubt that [he] remained a practising homosexual.”

We’ll never know, of course, but it certainly seems more than plausible that Leonardo was a gay or bisexual man who was hampered by both the law and public perceptions of the period.

Elagabalus

History is a complex thing, and the way we interpret the past is always changing. This was demonstrated in spectacular fashion when the North Hertfordshire Museum announced earlier this month that it was updating its display about Roman emperor Elagabalus – aka Marcus Aurelius Antoninus – to reflect an emerging view that she was, in fact, a trans woman.

According to contemporary accounts, Elagabalus, who ruled Rome between 218 and 222, had a male lover called Hierocles. She apparently loved to be referred to as his mistress, wife and queen, and she wore make-up and wigs. She also asked to be called a lady and reportedly tried to pay physicians to perform surgery that would have given her a vagina.

Announcing changes to its exhibition, the museum’s Kevin Hoskins said reclassifying Elagabalus as a woman was the “polite and respectful” thing to do, given she had asked that people refer to her as such.

The contemporary accounts are explicit, and one things seems obvious: Elagabalus could hardly be described as a cisgender person, and may very possibly have been an early example of a transgender woman. Maybe she would even have identified as non-binary or genderqueer.

Florence Nightingale

Historians have long speculated about the sexuality of the English social reformer and founder of modern nursing, Florence Nightingale.

To this day, nobody has been able to settle on whether she might have been a lesbian, asexual, or whether she simply recognised that getting married would strip her of her independence.

While there is no evidence of The Lady with the Lamp’s sexual relationships with anybody, there are suggestions in her writings that she may have harboured romantic feelings for women.

She once wrote: “I have lived and slept in the same beds with English countesses and Prussian farm women. No woman has excited passions among women more than I have.”

Nightingale had a number of intense relationships with women throughout her life, although it is possible they were purely platonic.

One of those was with her cousin Marianna Nicholson, but the relationship soured when Nightingale turned down a proposal from Marianna’s brother.

To complicate matters, Nightingale also wrote extensively about her general disdain for sex, which could point to asexuality.