‘I cancelled my pension when I was diagnosed with HIV – 30 years on, I’m alive and thriving’

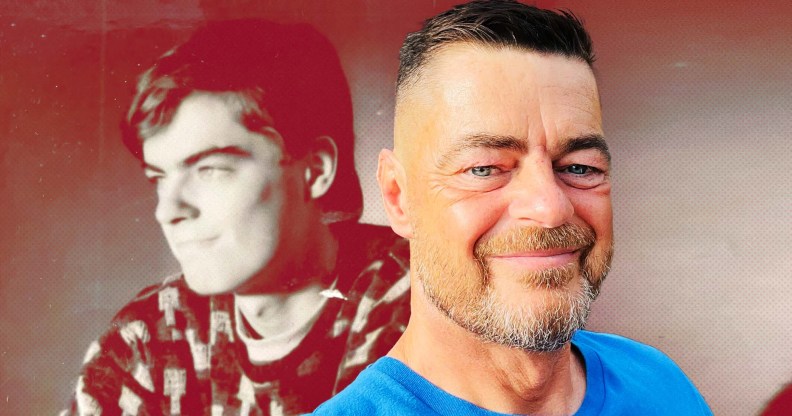

Ian Makinson was diagnosed with HIV 30 years ago. (PinkNews)

A couple of days after Ian Makinson was diagnosed with HIV in 1993, he was ironing in the front room of his house when it occurred to him that he should stop paying into his pension scheme.

He didn’t think he would live long enough to be able to enjoy the retirement most people dream about.

“It was just that void you disappear into, where you think, will I see 30? Will I see 40?” Ian tells PinkNews.

“Judging by what was happening at the time, and by the way people were disappearing, no, I didn’t ever envisage getting past 30. It was devastating.”

Ian was diagnosed with HIV against a backdrop of secrecy and shame. Very few people spoke about having the virus. Famous figures, such as Freddie Mercury, who went on the record to state that they were living with HIV, often died shortly afterwards.

Survival seemed impossible, so Ian set about doing what he could do to make his final years fulfilling. He and his then-partner – who had also been diagnosed with HIV – joined a support group in Leicester, and that helped for a while, but eventually he stopped going. He just couldn’t handle seeing people disappear, week after week, before learning that they had died.

“It felt like climbing a ladder. You start at the bottom, it’s a very long ladder, and people drop off the top and they’re never seen again. That was very much what it was like when you were diagnosed with HIV. You’d get the diagnosis and not long after, you died.

“People just disappeared off the scene, that was the scariest thing. You’d go out and you’d see regular people every week, then you’d start seeing fewer people… and you’d find out that person’s died or they’ve had a cancer or something very obscure. It was quite dark.”

Facing his HIV diagnosis was so painful that, after a while, Ian largely stopped going to his medical appointments.

“It was such a negative experience in the hospital. If you think the stigma [is bad] now, it’s nothing like it was then. It was an unpleasant experience. I used to duck out of more appointments than I actually went to for the first seven or eight years.”

In those days, HIV treatments were in their early stages, and they weren’t yet as effective as they are now. It wasn’t until 2003 – a full decade after he was diagnosed – that Ian went on treatment for the first time.

“I remember coming out of the clinic with a bag full of drugs, one of which was anti-sickness tablets and antidiarrheals,” he says.

By then, more-effective treatments were on the market, and the landscape was beginning to shift for people living with HIV. Today, people can live totally normal, long, healthy lives.

Treatment means that Ian’s HIV is now “totally under control”. The amount of virus in his blood is so low that it’s undetectable, meaning he can’t pass it on to anybody – even through sex without a condom.

Stigma still persists for those living with HIV

Much has changed, but the stigma persists. Statistics released by the Terrence Higgins Trust in 2022 showed that 74 per cent of those living with HIV had experienced stigma or discrimination because of their HIV to status.

Ian has plenty of first-hand experience of both.

“Once, going to a dentist, he refused to go near my mouth, to do anything that would possibly spike any blood or anything – this was while I was on treatment,” he says.

There was another incident when he went into hospital to have a lump removed from the side of his neck. He was shocked when he discovered he had been put last on the list of operations for the day because of his HIV status.

“They said, ‘Because you’ve got HIV, we put you last in the theatre because we have to clean the theatre down so much more after you’ve been in there’.

“That makes you feel really dirty, particularly [when it’s] coming from nursing staff and doctors.

“I can be quite a strong-willed person, and I remember challenging this. I said: ‘I don’t understand, because surely with an operating theatre, you’d clean it down after anyone’s been in there because you don’t know what anyone’s got, and it’s an operating theatre – it’s got to be sterile’. And they just said, ‘Oh no, we have to do it much more with an HIV person’. I was aghast and horrified.”

Those experiences were degrading, but Ian is optimistic about the future. Things are improving all the time when it comes to stigma.

“These days it is a lot better. I’m very open about my status – everyone at work knows.

“Work and employers have to be good [about it], but there is still a stigma there. I’m lucky now, I’m with a partner, a different [person] to who I was with 30 years ago.

“My current partner isn’t positive, he hasn’t got an issue with me being positive, he knows I’m on treatment. He was on PrEP but he doesn’t take it any more because he doesn’t need to, so from that perspective it’s fine. But where you do see it is on dating apps.”

Ian doesn’t use dating apps himself, but a friend of his was recently rejected by a sexual partner online because of his HIV status.

“I felt really bad for the guy because he shouldn’t have to have that these days. It’s terrible… When [you’re living with HIV] you’re probably more checked up and tested than anyone who doesn’t go to the clinic because they just go every so often [if] they need an STI check or something. It’s horrible to be on the side of that and that’s a real problem.”

This World Aids Day, Ian says the key to eradicating stigma is to educate more people, but he also says there’s an onus on individuals to do their own learning.

“If people knew and understood, they wouldn’t be afraid of it. That’s where the problem is.

“I can relate to the ‘I don’t want to know’ attitude because that was very much my attitude when Aids, as we called it then, was in in the news. We had tombstone adverts and all sorts of things.

“I didn’t want to test because I knew what my early days were like: I messed around, I had fun, but we didn’t know anything about it then.”

Nowadays, there’s no reason not to get tested, Ian says. HIV is a fully treatable and manageable condition, and it’s long past time that fear was removed from the equation.

“The fear is borne out of lack of knowledge. It really is no worse than being diagnosed with diabetes these days, and the worst case with diabetes is you have insulin tablets or injections and you alter your diet. It’s no different at all.”

To learn more about HIV and Aids research, testing and treatment, visit amFAR or the Terrence Higgins Trust.