Black History Month: 5 black LGBT heroes who fought for equal rights

As the UK celebrates Black History Month, it’s important to recognise some of the black LGBT+ activists who led the fight for equal rights across the world.

The contributions of black activists, from James Baldwin to John Amaechi, Laverne Cox to Bisi Alimi, have been invaluable to the LGBT+ movement.

Below we look at five people whose crucial work made a massive difference.

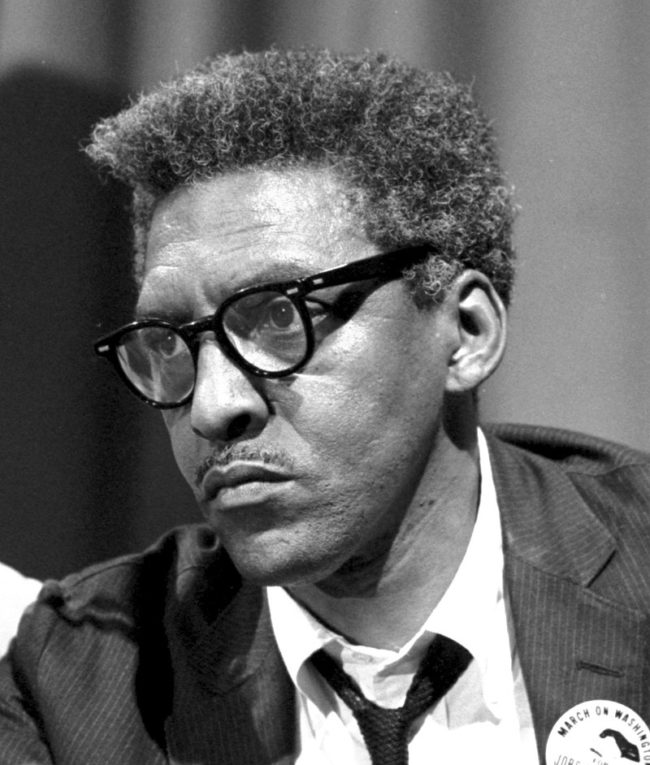

Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin (Public Domain/Warren K. Leffler)

The intellectual godfather of the US civil rights movement, Rustin was a mentor to Martin Luther King Jr.

A civil rights pioneer in his own right, Rustin was a leading figure in the early civil rights movement during the 1950s, and the key organiser for the 1963 March on Washington, where thousands of African-Americans flocked to defend equality.

Though he had a key role in shaping the civil rights movement, Rustin eschewed the role of a public figurehead after being arrested under anti-gay laws in 1953, fearful that his sexuality would be used against him.

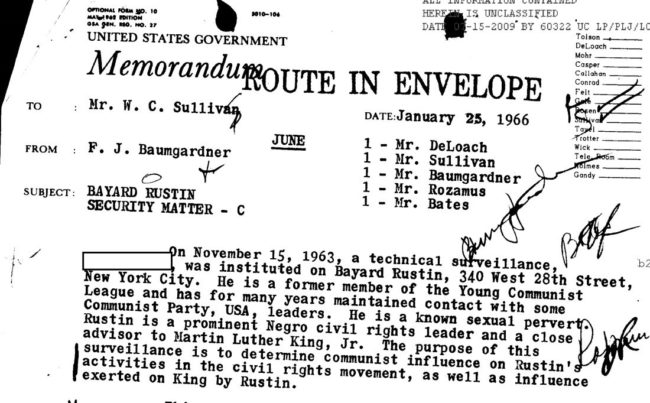

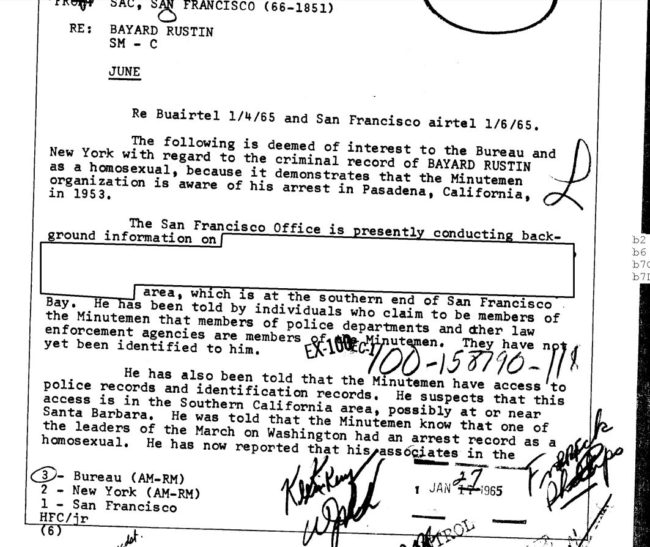

His fears were not unfounded. Unsealed FBI documents from 1966 describe Rustin as a “known sexual pervert” and notes his “position to wield considerable influence on King’s activities.” A 1965 intelligence report also details that he was “arrested as a homosexual in Pasadena.”

But despite facing so much intolerance, his lover and fellow civil rights activist Davis Platt later reflected that he was remarkably open for the time: “If anybody asked him, he would have told the truth, whereas most gay people back then would deny it (…) I never had any sense at all that Bayard felt any shame or guilt about his homosexuality. That was rare in those days.”

Rustin’s pioneering influence was not limited to the civil rights movement.

In the 1980s, he turned his attention to LGBT+ rights, lobbying Mayor of New York City Ed Koch in support of a proposed gay rights law at the height of the AIDS crisis.

The same year he gave a speech that cast the gay rights movement as the next step in civil rights.

He said: “Today, blacks are no longer the litmus paper or the barometer of social change. Blacks are in every segment of society and there are laws that help to protect them from racial discrimination. The new ‘n***ers’ are gays.

“It is in this sense that gay people are the new barometer for social change. The question of social change should be framed with the most vulnerable group in mind: gay people.”

Rustin passed away in 1987, having never achieved the same level of public notability of his contemporaries.

He was finally honoured with a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom by Barack Obama in 2013.

In a touching tribute, the Obama administration said: “[Rustin] fought tirelessly for marginalised communities at home and abroad. As an openly gay African-American, Mr. Rustin stood at the intersection of several of the fights for equal rights.”

Frank Mugisha

Frank Mugisha

While it’s easy to think of the battle for basic LGBT+ rights in the past tense, they are anything but for Ugandan activist Frank Mugisha.

The activist came out as gay at the age of 52, in a country where homosexuality is still illegal and highly stigmatised.

In 2004, he founded Icebreakers Uganda, a support organisation for LGBT+ people in Uganda, and in 2007 became the head of Sexual Minorities Uganda.

SMUG’s advocacy officer David Kato, a close friend of Mugisha, was murdered in 2011 after a magazine published his photo and called for his execution.

Despite a tidal wave of opposition to equality, Mugisha has worked tirelessly to fight for basic acceptance of LGBT+ people, battling a 2014 bill that would have introduced harsh new sentences for homosexuality.

The Anti-Homosexuality Act, dubbed the ‘Kill the Gays’ bill, was signed by President Yoweri Museveni, but was subsequently quashed on procedural grounds amid threats of trade sanctions.

SMUG and Mugisha later sued US evangelical preacher Scott Lively, who is alleged to have orchestrated the bill, for crimes against humanity. A US court found SMUG’s allegations to be true, describing Lively as a “crackpot bigot,” but rejected the lawsuit due to lack of jurisdiction.

Frank Mugisha

Mugisha was arrested by Ugandan police in 2016 during a raid on Uganda Pride, while threats also forced the cancellation of the event in 2017.

Writing in the Guardian last year, Mugisha said: “It took the murder of my friend David Kato and the threat of the death penalty against LGBT people for the international community to take notice of our plight.

“Now it feels like the LGBT community is becoming invisible again, and not just to Ugandan society.

“We need the British government, the EU and the US to keep talking to the Ugandan government. We need the persecution of LGBT people to be on the agenda of the Commonwealth. And we urge the EU to appoint a special representative on LGBT rights.

“The fact that we have been forced to cancel Pride Uganda is one more sign of our growing invisibility.”

Marsha P. Johnson

Marsha P. Johnson

Few LGBT+ rights leaders have been so utterly rejected in their own lifetimes as Marsha P. Johnson.

Fleeing a homophobic upbringing in 1963, the African-American activist left for New York City “with $15 and a bag of clothes,” adopting her chosen name and living as female.

She variably identified herself as a drag queen or a transvestite, living decades before the modern transgender movement.

Johnson became a prominent figure on New York’s gay scene, and is remembered as one of the key instigators of the 1969 Stonewall Riot, considered the birthplace of the LGBT+ rights movement.

She helped instigate the uprising after the New York City Police Department raided the Stonewall Inn, one of the community’s few sanctuaries in the city. Johnson was at the forefront of the pushback against police during the violent clash.

Johnson played a leading role in the rights movements in the wake of Stonewall, co-founding the Gay Liberation Front. She also ran the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries alongside close friend Sylvia Rivera, which worked to help young homeless queer people.

Marsha P Johnson

Although Johnson fought for queer acceptance, throughout her lifetime she remained an outcast—living on the streets and surviving through sex work, battling mental illness and suffering daily indignities.

Her role in Stonewall was largely erased from early accounts, and she was banned from the Pride parade in New York for several years, with gay rights activists claiming that letting “drag queens” march would give them a “bad name.” Johnson defiantly attended anyway.

Johnson, who was also a leading voice in the ACT UP movement during the AIDS crisis, died in 1992 under suspicious circumstances.

Despite calls for a murder investigation from the LGBT+ community, Johnson’s death was quickly dismissed as a suicide by the NYPD. Protests followed, but calls for justice fell on deaf ears until the case was finally re-opened in 2012.

Erased from history for so many years, Johnson’s work can now be finally celebrated for the pioneering activism it was.

The activist was even given a obituary in the New York Times this year, more than 25 years on from her death, as the newspaper acknowledged its troubling legacy towards women, queer people and people of colour.

Susan Stryker, an associate professor of gender and women’s studies at the University of Arizona, told the NYT: “Marsha P. Johnson could be perceived as the most marginalised of people — black, queer, gender-nonconforming, poor.

“You might expect a person in such a position to be fragile, brutalised, beaten down. Instead, Marsha had this joie de vivre, a capacity to find joy in a world of suffering.

“She channeled it into political action, and did it with a kind of fierceness, grace and whimsy, with a loopy, absurdist reaction to it all.”

Stormé DeLarverie

Stormé DeLarverie

Born in 1920 New Orleans to an African-American mother and a white father, butch lesbian Stormé DeLarverie was ‘othered’ by society, but found a string of communities to call home.

She found solace in jazz bars, where DeLarverie found work as a singer, dressed firstly as a woman, and then as a man. At the circus, where she made a living horse-jumping, riding sidesaddle until she was injured by a fall. In Chicago, where she became a bodyguard to mobsters.

Her love of performing not abating, in the 1950s and ’60s she joined travelling drag troupe the Jewel Box Revue, becoming the only drag king in the line-up of female impersonators.

History would call on DeLarverie in New York City, at the Stonewall Inn in 1969.

Though the precise details of what happened during the June 28 uprising are lost to history, activists say that the unrest began when a “butch lesbian” in handcuffs began fighting with police, throwing the first punch at an officer.

The Stonewall Inn in 2016 (Nick Duffy)

DeLarverie, multiple accounts suggest, was that woman.

Her friend Lisa Cannistraci told the New York Times: “Nobody knows who threw the first punch, but it’s rumoured that she did, and she said she did. She told me she did.”

Of her own participation, DeLarverie made clear: “It was a rebellion, it was an uprising, it was a civil rights disobedience — it wasn’t no damn riot.”

In the wake of Stonewall, DeLaverie became a leading member of the Stonewall Veterans’ Association, and was a regular at New York’s Pride parade.

In the decades after Stonewall, DeLaverie found work as a bouncer and bodyguard at lesbian bars across the city, and became known as the “guardian of lesbians in the [gay] village.”

Cannistraci added: “She literally walked the streets of downtown Manhattan like a gay superhero. She was not to be messed with by any stretch of the imagination.”

The activist lived with Diana, her partner of 25 years, until Diana’s death in the 1970s.

DeLaverie continued working as a bouncer until age 85. She passed away in 2014, aged 93.

Lady Phyll

Lady Phyll

Phyll Opoku-Gyimah, known to all as Lady Phyll, has given a voice to a generation of young black LGBT+ people who did not feel represented by the mainstream LGBT+ movement.

She co-founded UK Black Pride, which was conceived as an event in 2005 to give voice to the minority communities within the movement.

But UK Black Pride has grown to become much more than an event, serving as a protest promoting “unity and co-operation among all Black people of African, Asian, Caribbean, Middle Eastern and Latin American descent, as well as their friends and families, who identify as Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual or Transgender.”

Lady Phyll’s engagement with the LGBT+ community is extensive, serving as a trustee of Stonewall and fighting for equality through the PCS union.

The activist was offered an MBE in 2016 but turned it down, citing the British colonial history of anti-LGBT laws.

She said: “As a trade unionist, a working class girl, and an out black African lesbian, I want to stand by my principles and values.

“I don’t believe in empire. I don’t believe in, and actively resist, colonialism and its toxic and enduring legacy in the Commonwealth, where—among many other injustices—LGBTQI people are still being persecuted, tortured and even killed because of sodomy laws, including in Ghana, where I am from, that were put in place by British imperialists.”

“I’m honoured and grateful, but I have to say no thank you.”

Lady Phyll

Lady Phyll hinted at further ambitions earlier this year, when she considered a bid to become Member of Parliament for Lewisham East.

She said: “I come from a long line of women who refused to be silent. Women who stood up to be counted and who have worked tirelessly in advancing equality, justice and freedom for all.

“While I am nervous about stepping forward in such a public arena, I do so with the confidence of all those who believe in me, who know that our future in this city and far beyond is worth fighting for.”

The activist eventually withdrew her name from contention, citing an “unexpected family situation.”