Non-gendered activist Christie Elan-Cane on lifelong fight for same dignity and rights as any human

Christie Elan-Cane. (DANIEL LEAL-OLIVAS/AFP/Getty)

Christie Elan-Cane is a non-gendered activist whose landmark case about ‘X’ gender markers in passports was the first trans civil rights case to be heard by the UK’s Supreme Court.

Arguments against the Home Office’s policy of only issuing passports with an ‘M’ or ‘F’ gender marker were heard by Supreme Court justices over two days in July 2021.

On 15 December, the Supreme Court unanimously dismissed Christie’s appeal. The case argued for an ‘X’ marker to indicate an unspecified or undisclosed gender to be made available for British passport holders, which would be available to anyone, including those whose gender identity is neither male nor female.

During the historic hearing, Supreme Court justices were told how passports with an ‘X’ gender marker have been available in multiple countries for decades, are “nothing controversial“, and that there is “no evidential basis” for the government’s claim that ‘X’ gender markers in passports would have an “adverse impact on the state”. Government lawyers told the court that implementing ‘X’ gender markers in passports would be “extremely difficult“.

For Christie, who uses per/perself pronouns and has been fighting to legitimise per identity for three decades, these arguments were the culmination of a long, isolated struggle.

Speaking to PinkNews after the momentous hearing in July, Christie explained how the long-running legal fight began after a “fateful decision” to talk to a BBC producer in 1992, why per will only accept an ‘X’ passport if there’s an overall policy change, and what they think of the new wave of trans activism that has emerged during their lonely, 30-year fight for legal recognition.

Christie Elan-Cane: ‘I was forced out of the workplace’

Christie Elan-Cane first asked the British government for a passport with an ‘X’ gender marker in 1995, but the discrimination per experienced for per identity began three years earlier.

“In early 1992 I made a fateful decision,” Christie explains. Per had been going to a trans social group called TV/TS, nicknamed “the French place” because of its location, and a BBC producer had got in touch, asking to speak to an “androgynous person”.

“I agreed and in my naïveté thought it would be a way of coming out at work,” per says. “To say it backfired would be an understatement.”

Pakistan’s first non-binary passport, issued to trans activist Farzana Riaz. (Abdul Majeed/AFP/Getty)

Christie wasn’t out as non-gendered at work at the time, though per had “embraced” per identity after having surgery in the late 1980s. When Christie’s story appeared in the media, the backlash was immediate and acute.

“Things were not going well at work, I ended up leaving and couldn’t get another job,” Christie explains. “I was forced out of the workplace.”

After years of struggling to find employment, Christie’s passport was due for renewal in 1995. But when per called the passport office and explained that per is non-gendered, “they said no, that I couldn’t possibly have anything other than male or female, and that if I didn’t return the form in that way it would just get sent back,” Christie says.

“From that point, all I could do was fight to legitimise my identity.”

Finding community on the gay and lesbian scene

Growing up, like many, Christie Elan-Cane thought per must be the only person who was “neither male nor female”.

I had been open about my identity, since the time that I was able to basically articulate and to take in that I was neither male nor female,” per says, “even though I thought, ‘Is that actually possible?’”

“Because at the time, society was completely different, I can’t express enough how gendered the structure of society was.”

Working as a club promoter and DJ in the 1980s, Christie had found some sense of community on the “L and G” scene, as it was then called.

“This is the time before and during when HIV and AIDS was becoming more known about,” Christie says. “It was quite hedonistic. There was not a great deal for women. At the time, I didn’t feel I was female, but I was preoperative and I didn’t think there was anything else. So I wouldn’t say I felt at home [in lesbian spaces] but I felt more at home there than I did in other places.”

It wasn’t until Christie found the trans social group at “the French” place that per really found per people.

“It was a revelation,” per says. “I found people who, even though they were trans women which I wasn’t, there was an empathy there that was lacking from LGB spaces. So that was when I felt I’d found the right community for me.”

It was this group, which Christie went to in 1991 and 1992, that later led to the conversation with the BBC producer that outed Christie at work and sparked per’s legal fight.

‘I thought of myself as being quite ordinary, but I was in this extraordinary situation’

Non-gendered campaigner Christie Elan-Cane has fought for social and legal recognition for 30 years.

However, while Christie Elan-Cane had found community among other LGBT+ people, per would soon be alone again in per battle for non-gendered legal recognition.

“I wasn’t a political person,” Christie admits. “There are wonderful people like Peter Tatchell who have politics and protests ingrained in them. I was not that person, not at that time.

“It was something that I was forced into doing after years and years of trying to legitimise my identity. I had literally no help apart from my partner, I was entirely on my own.”

Christie describes how legal trans activists, such as groups like Press For Change, who were engaged in a parallel fight for legal gender recognition that ultimately led to the creation of the Gender Recognition Act (GRA), were “not on my side”.

“The GRA was an effective means to enable some – it wasn’t clear at the time how few, but it’s tiny, though it was assumed they were the majority – who wanted to transition and then sort of cast off their previous role and just disappear into the mainstream,” Christie says. “People like me would never fit in that criteria because it only recognised male or female.”

Christie says trans people who weren’t men or women were “effectively just told to shut up and not rock the boat” when it came to thinking about a form of official, legal gender recognition that could include non-gendered or non-binary people.

Between losing per job, being refused a passport in 1995 and then “everything that happened with the GRA”, Christie felt as if “the shutters had come down”.

“There was no interest in what I was doing,” per says. “It felt like it really set things back for me and I went into what I can only describe as a spiral of despair for a long time.”

Deciding to fight

After spending years questioning per decision to come out publicly as non-gendered, which had a calamitous impact on per work and life, Christie Elan-Cane had a “epiphany moment” reading the Universal Declaration of Human Rights sometime around 2005.

“Article One says all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and in rights,” Christie recalls. “And I thought, I’m a human being, I’ve got rights, why am I being treated like this? I can’t allow myself to be treated like this. Suddenly I became angry, and I really started fighting back.”

Around the same time, Christie was becoming more aware of how many other people had gender identities similar to per. Currently, according to the government’s 2018 National LGBT Survey, just over half of trans people in the UK are non-binary.

“I realised there were quite a few more of us. Whereas 10 years earlier I’d never met anybody else. It was a very different time,” per says. With the help of lawyers at Clifford Chance, Christie sued the Home Office over its refusal to give British citizens the option of an ‘X’ gender marker in their passports.

Per lost in 2018 and then lost again in 2020. But the Supreme Court agreed to hear Christie’s case, scheduling a two-day hearing for July 2021.

And here they are!

Outside the UK Supreme Court today with my wonderful legal team and my wonderful partner @davidb327, pic.twitter.com/vMYwMfEWc2

— Christie Elan-Cane (@ChristieElanCan) July 13, 2021

Non-binary legal recognition

The struggle for non-binary legal recognition is ongoing, with more than 136,000 people signing a petition this year asking the government to legally recognise non-binary identities – meaning that non-binary trans people could correct their birth certificates in line with how adult trans men and women currently are able to.

The Tories have said several times that non-binary legal recognition would have too many “complex practical consequences” to enact – despite 58 per cent of respondents to the 2018 consultation on reforming the GRA saying that gender recognition laws should be changed to include non-binary people.

But while Christie Elan-Cane isn’t non-binary – “I don’t like that term and I don’t feel it applies to me. I am non-gendered” – per’s court case could have had widespread and significant ramifications for non-binary people in the UK, who might have finally been able to obtain passports with an ‘X’ gender marker if Christie was to win per case.

Explaining why the ‘X’ marker has been per lifelong fight, Christie says: “On the basis that ‘male’ and ‘female’ are terms that aren’t going away anytime soon, if ever, I think it would be better to have a third option of ‘neither’ or ‘other’. I think that would solve more problems than it would create in terms of getting rid of those terms altogether.”

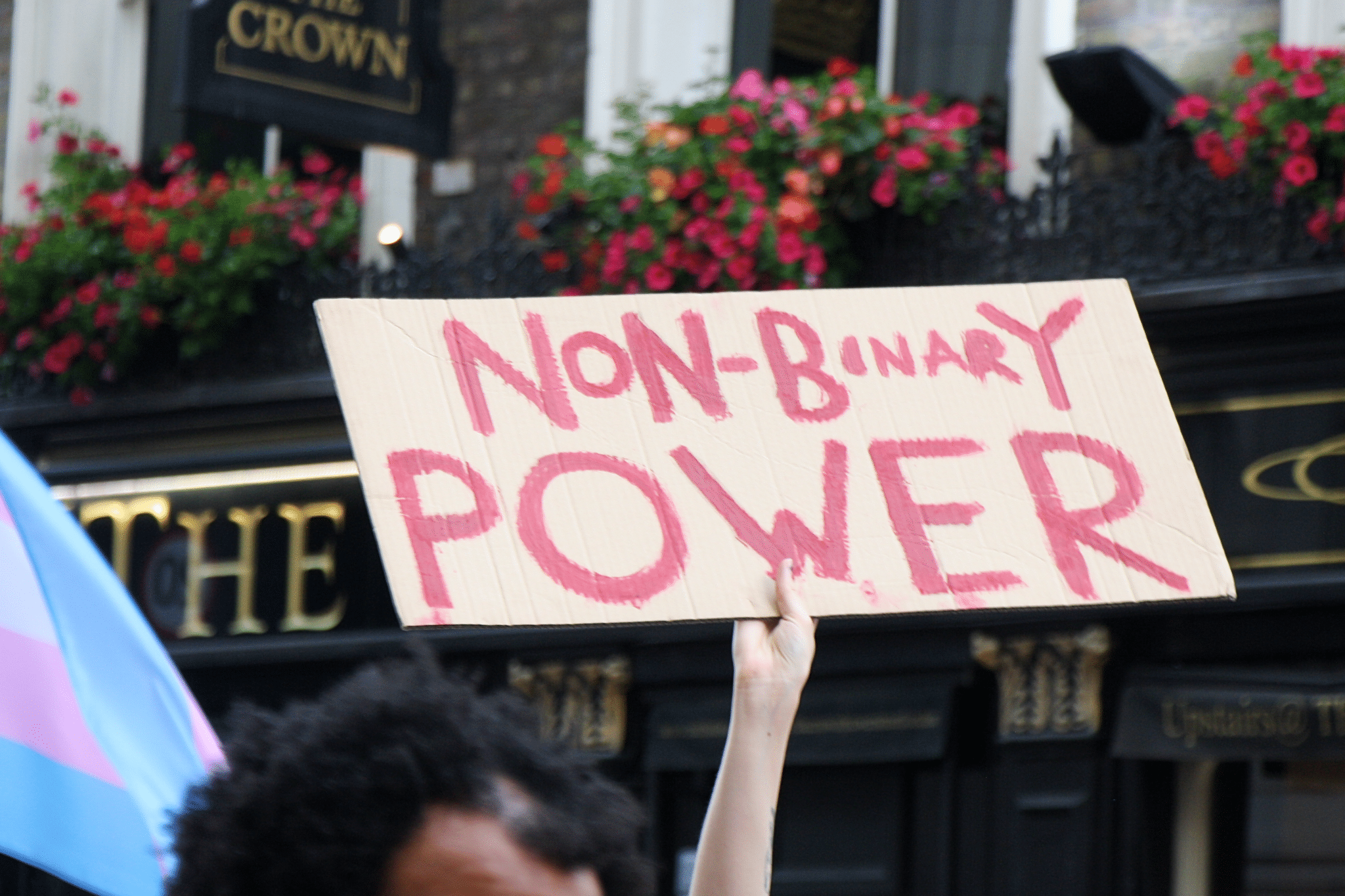

A placard reading “Non-binary power” at London Trans+ Pride, 2021. (Charlie Mathers/@charlie.mathers)

Belgium recently committed to legally recognising non-binary people. It will be the third European country to do so, following Germany and Iceland.

Malta, most Australian territories, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Uruguay all legally recognise non-binary genders. Countries including Denmark and New Zealand, several US states and Canadian territories all offer ‘X’ gender options on legal documents for non-binary citizens.

These countries recognise, as Christie says, that ‘X’ passports are “a way of making people in our position able to acquire a passport, an essential travel and ID document, that doesn’t require us to make a false declaration and carry a document that is entirely misrepresentative of who we are”.

Per adds: “I’ve always wanted to work for things that were possible, what I felt was possible. I felt X passports were possible, and that’s why I’ve made it the focus of my campaign.”

Christie Elan-Cane dreams of flying

Christie Elan-Cane is clear: what happened to per 30 years ago, losing per job for coming out as non-gendered, couldn’t happen today.

In fact, a 2020 employment tribunal against Jaguar Land Rover found in favour of a non-binary applicant, with the judge affirming that non-binary and genderfluid people are protected from discrimination by the “gender reassignment” protected characteristic of the 2010 Equality Act.

However, this progress “doesn’t change things” for Christie. “I’m still fighting and I can’t get back the last 30 years of my life, which have effectively been stolen from me,” per says. “So I do feel detached.”

As well as not liking the term non-binary, Christie says per “doesn’t agree” with the current focus of trans activism on younger people “and their 100 different gender identities”.

“I don’t agree with that at all,” Christie says. “It’s overcomplicating things. I see myself as having no gender, I don’t see any point to having labels. I know not everybody is going to agree with me on that.”

Perhaps if per fight had begun later, and been less isolated, Christie’s story would be different. But as it stands, Christie has begun to think about what per will do after the long years of legal fighting come to an end.

“One thing I would like to do, if time permits”, per says, is learning to fly. “I’ve not quite given up on that.”

Before Christie lost per job in the early 90s, per had started taking flying lessons. “They were the first thing to go when I lost my source of income, so I never got a pilot’s license,” per explains. “I don’t know whether it will be too late for me to take that up again, or whether I’d ever be able to afford to, but that’s something that if I can, I’ll pursue at some point in the future.”

Asked what it is per loves about flying, Christie says it’s “the freedom”.

“I just loved it. I liked the freedom, of being up there. But I’d only just started the [flying] lessons, so I’d have a very long way to go.”