How Tom of Finland went from belittled ‘pornographer’ to one of the world’s most iconic artists

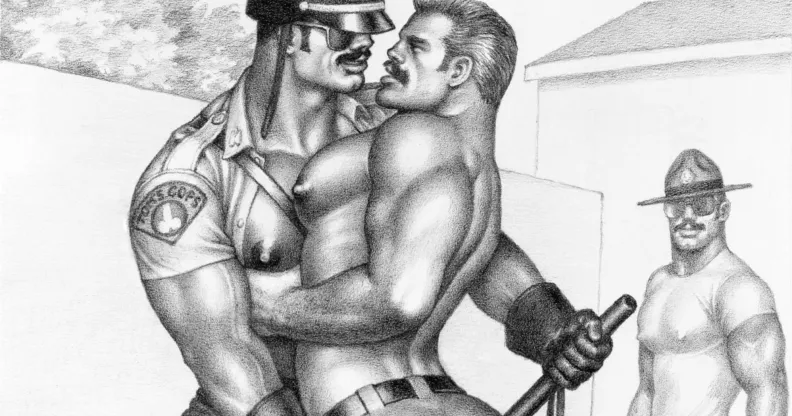

One of Tom of Finland’s drawings. (Tom of Finland Foundation)

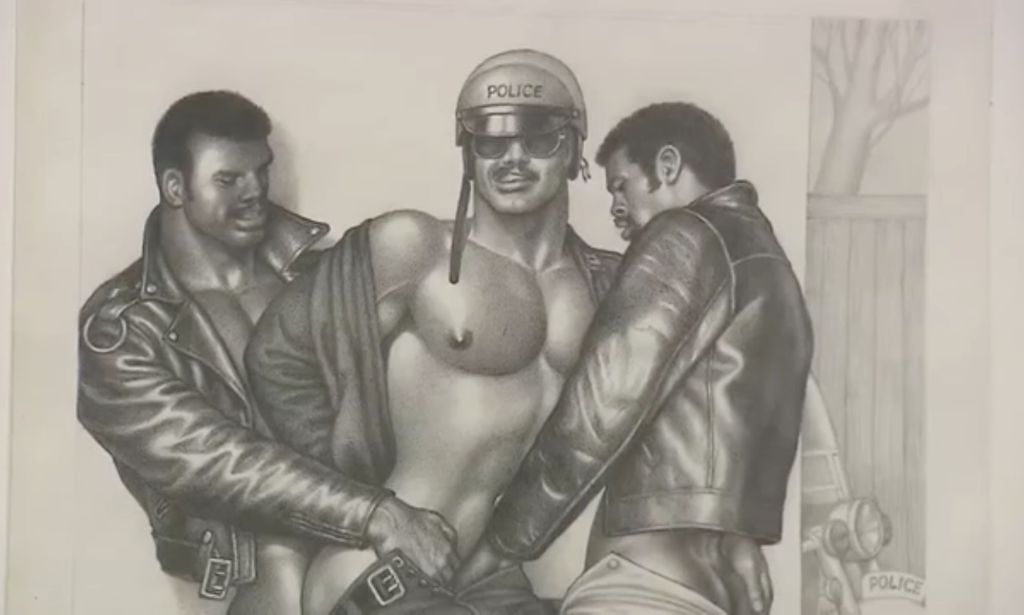

Tom of Finland created art that was deeply subversive and powerfully erotic – but he was often dismissed as a “pornographer” during his lifetime.

The artist, whose real name was Touko Valio Laaksonen, has become a household name for his iconic erotic drawings of men with bulging muscles, tight trousers and leather jackets. Defiantly queer, his works are found on T-shirts and vodka bottles, and in respected galleries around the world.

But during his lifetime he was largely shunned by many in the art world, his close friend Durk Dehner recalls.

“[They] were giving Tom reviews that classified him as first a pornographer, then a bit later as an illustrator,” Dehner tells PinkNews.” “They did not perceive what the content of his work was outside of horny drawings.

“They did not see that he was creating a vision for his fellow homosexuals to relate to.”

Laaksonen was born in 1920 in Finland, where homosexuality remained a criminal offence until the 1970s.

Somehow, he found the courage to start publicising his art, even despite the fact that homosexuality was deeply taboo. In 1957, some of his drawings were published in an American magazine called Physique Pictorial – but even then, he had to bow down to the law. It was illegal to depict “overt homosexual acts” in the US at that time, so he had to err on the side of caution with his early drawings.

The attitudes and culture of the 1950s and 1960s meant that Laakonsen didn’t really get the chance to fully thrive as an artist until the 1970s. It wasn’t until 1973 that he finally found himself in a position to give up his full-time job at an advertising agency so he could dedicate himself fully to his craft.

In 1977, Laaksonen travelled to the United States to exhibit his work – and it was there that he met Dehner for the first time. The pair became friends and founded the Tom Of Finland Company together, an organisation dedicated to protecting his copyright and his images.

To this day, Dehner – who is also the co-founder of the Tom of Finland Foundation – remembers how clear Laaksonen’s vision was, and he recalls how the art world slowly but surely came to respect and embrace the man who defined queer erotic imagery.

“Tom saw how homosexuals were not being provided with any positive role modelling, they were viewed as perverts, criminals, degenerates, as society’s outcasts,” Dehner tells PinkNews.

“He made it his mission to see if he could affect change within the gay community by presenting his men in a positive, happy, well-adjusted [place]… Tom stole the male archetypes of the heterosexual alpha male and turned him queer.”

Tom of Finland became revered as a ‘fine artist’

The men in his drawings were free, uninhibited, and never seemed to care whether anybody else was watching them. That was appealing for queer men of Laaksonen’s generation, Dehner says – and as time went by, he developed an ardent fan base.

But he never encountered anything like overnight success. While he had an ardent queer following by the time the 1970s rolled around, he was still largely ignored by the mainstream art world.

In the 1980s, things gradually started to change. At that stage, Laaksonen was already near the end of his life.

“During the ’80s, he went from being an illustrator to being a respected draftsman and that flowed over into being called a fine artist,” Dehner recalls.

“It was not until the early 2000s that the words ‘master draftsman’ and master artist’ were used about him.”

Laaksonen never got to see just how successful his work would become. He died in 1991 at the age of 71 – while widely respected by that point, his drawings have since taken on a particular cultural significance unlike anything seen during his lifetime.

“He does not go out of style because he represents mankind in a sexual enlightenment,” says Dehner, who recalls seeing lines of men queuing to meet Laaksonen when he held an exhibition in San Francisco in the late 1970s – that experience showed him that the drawings were about so much more than bulging muscles.

“I got to witness long lines of young men who stood so patiently so they could look him right in the eye and shake his hand and thank him for giving them a positive image of how they could be happy and well-adjusted.

“I realised right then that he was not just a good artist, he had actually changed the way people viewed themselves. He changed the way things were then and now.”

Public perceptions of his work changed rapidly following the artist’s death. In 1995, the Tom of Finland Clothing Company launched a fashion line which drew inspiration from his drawings and contemporary trends, an act which helped solidify his work as officially mainstream.

Today, his work is exhibited in some of the world’s most renowned art galleries, including New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Its placing in that revered institution says a great deal about what his work has come to mean – and how much perceptions have changed since he was ostracised and dismissed as a pornographer.

For queer people, the significance of his work has only deepened as the years have gone by.

It’s been more than 30 years since he died, but Dehner sees just how vital a figure he was – and continues to be – within queer communities.

“Tom was and is our father, the father we did not have,” he says.

How did this story make you feel?