The incredible life of Roberta Cowell: British trans innovator, war pilot and racing driver

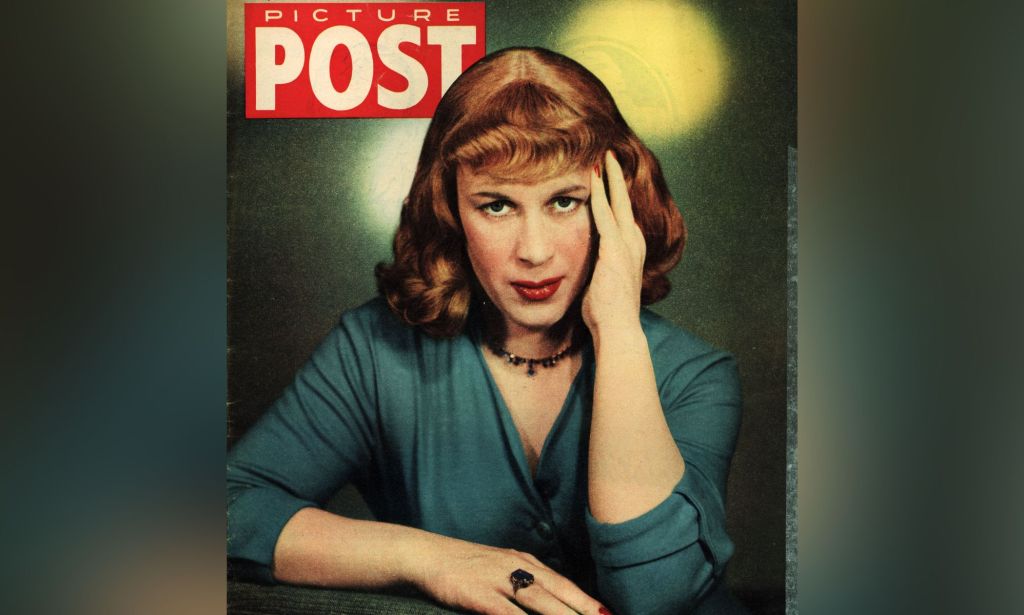

Roberta Cowell was a WWII Spitfire pilot, prisoner of war, racing motorist and the first trans woman to undergo gender-affirming surgery in the UK. (Getty)

Roberta Cowell led an extraordinary life as a WWII fighter pilot and competitive racing driver, and was the first known trans woman in the UK to undergo gender-affirming surgery.

Cowell, also known as “Betty”, had arguably one of the most remarkable existences of the 20th century and paved the way for generations of trans people.

She was a racing driver, a Spitfire pilot, a prisoner of war and a trans history maker. Cowell attracted intense media attention in the 1950s when news broke that she was among the first in the world, certainly the first in Britain, to undergo gender-affirmation surgery.

Yet, interest in her story faded over time, and Cowell’s legacy was mostly forgotten until she died in 2011 and news outlets reminded the world about her incredible journey.

Roberta Cowell was born in Croydon, south London, in 1918 and was the child of prominent surgeon Major-General Sir Ernest Marshall Cowell.

From a young age, Cowell developed a deep interest in cars, engineering and racing. She wrote in her autobiography: “It was the be-all and nearly the end-all of my existence.”

Yet, she also knew that she was “not a normal male”. She believed her “body had certain feminine characteristics” from an early age, and she felt her “aggressively masculine manner compensated for this”.

To fuel her love of racing, Cowell would sneak into the pits of the Brooklands race circuit, dressed in overalls to help the mechanics. She soon became a racing driver – she wrote that she jumped behind the wheel the “moment [she] was legally old enough to drive on the road”.

Roberta Cowell eventually joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) as a pupil pilot in 1935, and her ambition was to become a fighter pilot. However, she suffered from severe air sickness, and she was deemed “permanently unfit for further flying duties with the RAF” as a result.

“I was not very upset about this; compared with motor racing, I found flying a bore,” she wrote.

From then until the outbreak of WWII, she studied engineering at University College London (UCL) and followed her passion for automobile racing, going on to compete in the Antwerp Grand Prix in 1939.

While at UCL, she met Diana Carpenter, a fellow engineering student who was also a racing fan, and the pair married in 1941 before having two children together.

Cowell returned to the skies once more to become a pilot and served in a front-line Spitfire squadron assigned to aerial reconnaissance over German-occupied territories.

While flying over Germany in 1944, her plane crashed, and she was captured by Nazis. She was eventually moved to the Stalag Luft I prisoner of war camp, where she would remain until the end of the war.

After the war, Roberta Cowell started racing competitively again but was consumed by depression linked to the trauma she experienced during the war and a growing discomfort with her body.

By 1948, she had separated from her wife and left her family to seek help. It was during therapy that she discovered that her “unconscious mind was predominantly female”, and soon the bravery that she poured into racing and flying flowed into a different aspect of her life – transitioning.

“It became quite obvious that the feminine side of my nature, which all my life I had known of and severely repressed, was very much more fundamental and deep-rooted than I had supposed,” she wrote.

Cowell started hormone therapy, and her journey reached a turning point when she met British physician Michael Dillon – the first trans man to have a phalloplasty on record. She said the encounter was “so shattering that the scene will be crystal-clear in [her] memory for the rest of [her] life”.

In 1951, Cowell underwent vaginoplasty – a gender-affirming surgical procedure to create a vagina – carried out by Sir Harold Gillies. The procedure was the first of its kind in Britain.

She returned to racing with some success in the 1950s, and became the subject of public interest in 1954 after news outlets published articles about her history as a racing driver and war hero as well as her gender-affirming medical journey.

Sadly, Cowell faced financial difficulties, found it difficult to secure employment and suffered discrimination which forced her to eventually quit racing.

Controversially, Cowell asserted that she was intersex throughout periods of her life not only to enable her to get gender-affirming surgery and legal recognition as a woman, but also as a means to distance herself from other trans people.

In a brief final interview in 1972, Roberta Cowell condemned other trans people who underwent gender-affirming surgery. She described them as “freaks” and criticised the ‘permissive society’ of the time.

Cowell withdrew from public life, and her final years were spent in London in relative isolation. When she died in 2011 aged 93, her story had faded into obscurity.

But Cowell’s name and legacy lives on in the years since her death.

Her transition preceded decades of public discourse over trans and LGBTQ+ rights, and it serves as an example of the monumental impact that gender-affirming healthcare can have on trans peoples’ lives.

How did this story make you feel?