The Blue Caftan director on giving voice to queer Moroccans: ‘This film is about the freedom to love’

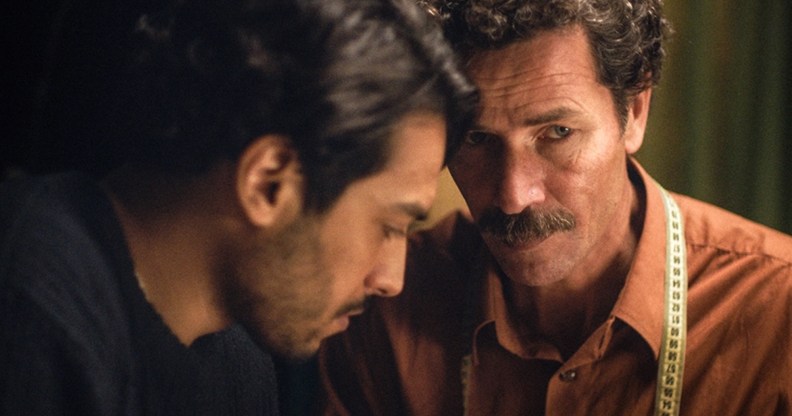

Maryam Touzani, director and co-writer of The Blue Caftan talks to PinkNews about the importance of portraying LGBTQ+ Moroccans on screen. (Strand Releasing)

Maryam Touzani, creator of groundbreaking Oscar-shortlisted movie The Blue Caftan, discusses the importance of bringing the LGBTQ+ Moroccan experience to the big screen.

Global LGBTQ+ stories are having a moment right now. With viewers swept away by the critically acclaimed Pakistani trans drama Joyland and the tender French Oscar nominated coming-of-age film Close, Morocco’s latest LGBTQ+ film The Blue Caftan is joining a growing wave of queer stories rarely seen on the big screen.

Co-written by Touzani and Nabil Ayouch, The Blue Caftan follows the bittersweet love story between a closeted Moroccan tailor Halim (Saleh Bakri) and his apprentice Youssef (Ayoub Missioui). We also meet Halim’s wife Mina (Lubna Azabal) who is dying of a terminal illness and must confront her mortality while grappling with her husband’s sexuality.

“It’s always a bit complicated to know when a story begins. Here I know when the trigger happened,” Touzani tells PinkNews about the inspiration behind this story of forbidden love.

It came in the form of a mysterious man she encountered during filming for her previous project, Adam, who touched her “very deeply”.

“I felt there were a lot of things that he wasn’t saying about his life, that there was a whole part of his existence that lived in the shadow,” she recalls.

“I went back to see him quite a few times but I never asked him any personal questions because it didn’t feel like my place, but the emotional impact it had on me was very strong and it really lasted.”

At its core, The Blue Caftan is about the things that are left unsaid between star-crossed lovers, life partners, long-held friends and long-lost family, all explored through the lens of queerness.

“It’s very hard to have to pretend on a daily basis,” Touzani explains. “What does it mean to wake up everyday and pretend to be somebody you’re not? What would it mean for a man, and the wife of a man who is gay to live in this situation? Then I started writing.”

LGBTQ+ Moroccans are all too familiar with having to hide their true selves, as homosexuality is illegal and punishable with up to three years imprisonment in the conservative country.

“People are suffering because they cannot openly be who they want to be and love who they want to love,” says Touzani. “For me it was really important to give this community a face. Nobody can tell you who you can and cannot love or how you can love them.”

Touzani truly saw the impact of her work after hearing testimonies from audience members who had never before considered the LGBTQ+ experience. “[The film] made them feel emotions they were not expecting to feel and I think that is the role of cinema. To create empathy, put yourself into other people’s shoes and break boundaries.”

What elevates The Blue Caftan is the richness of Moroccan culture woven into the plot as Halim undertakes the task of creating a blue caftan – a belted tunic – that is eventually bestowed to his wife Mina on her deathbed.

“For me, the caftan is a character,” Touzani explains. “It was inspired by a caftan that I had seen my mother wearing ever since I was a child. I always dreamt of the moment I would wear it. The day she gave it to me I realised how beautiful this transmission was.

“I had a feeling that the soul of the person who made it was imbued in the caftan.”

To make the film as authentic as possible, actors Bakri and Missioui attended embroidery lessons and spent time observing the art form in tailor shops. Touzani took care to reflect that level of detail throughout the film, including in the depiction of Islam’s relationship to homosexuality.

“I think that it’s very important to have nuance,” she says. “Mina is a Muslim woman, a fervent believer, but that doesn’t keep her from being open-minded. I don’t like anything that is full of cliches or stereotypes. I tried to be as truthful as I could.”

It is Mina’s struggle with her impending death that eventually gives her the “courage” to face up to the truth of her husband’s sexuality and yearning for Youssef.

“Mina has to go through her own journey in order to be able to face her fears and apprehensions and to realise that what is most important for her is that the man she loves so deeply is happy, that he be proud of who he is, that he can love himself,” Touzani continues.

For Touzani, the story is too important to hold anything back, even though she faced the risk of homophobic backlash.

“Of course I knew it was a sensitive subject,” she admits, “and that everyday could be a challenge but at the same time I knew this film had to exist. I don’t like to get caught mentally in fear.”

Although The Blue Caftan might appear to be a tragic story on the surface, from the unfulfilled lust between Halim and Youssef to Mina’s death, there is also an undeniable sense of hope.

As Mina takes her last breath, she gives her blessing to Halim and Youssef, and we see a final shot of the two of them sitting side by side at the very beginning of their budding relationship.

“My favourite aspect of Halim and Youssef is all that is yet to be discovered between them,” says Touzani. “They are two men that are falling in love. The film begins with Youssef’s admiration for this master craftsman and that admiration little by little transforms into actual love for the human behind it.

“I like all the possibilities of what they are going to become and that’s why I closed on that in the film.”

And it is this message of hope that she hopes queer Moroccans will hold onto when the credits start to roll.

“This film is about the freedom to love however you want, whether you are in Morocco or anywhere else in the world. There are countries that are very modern that still hold so many judgements about the LGBTQ+ community, so it is not limited to our society.

“For queer Moroccans it’s important that they feel they exist as well. Characters like these have not existed and I believe that they have to exist, that these are stories that have to be told.”

The Blue Caftan is available to watch in select UK cinemas and on MUBI.

How did this story make you feel?