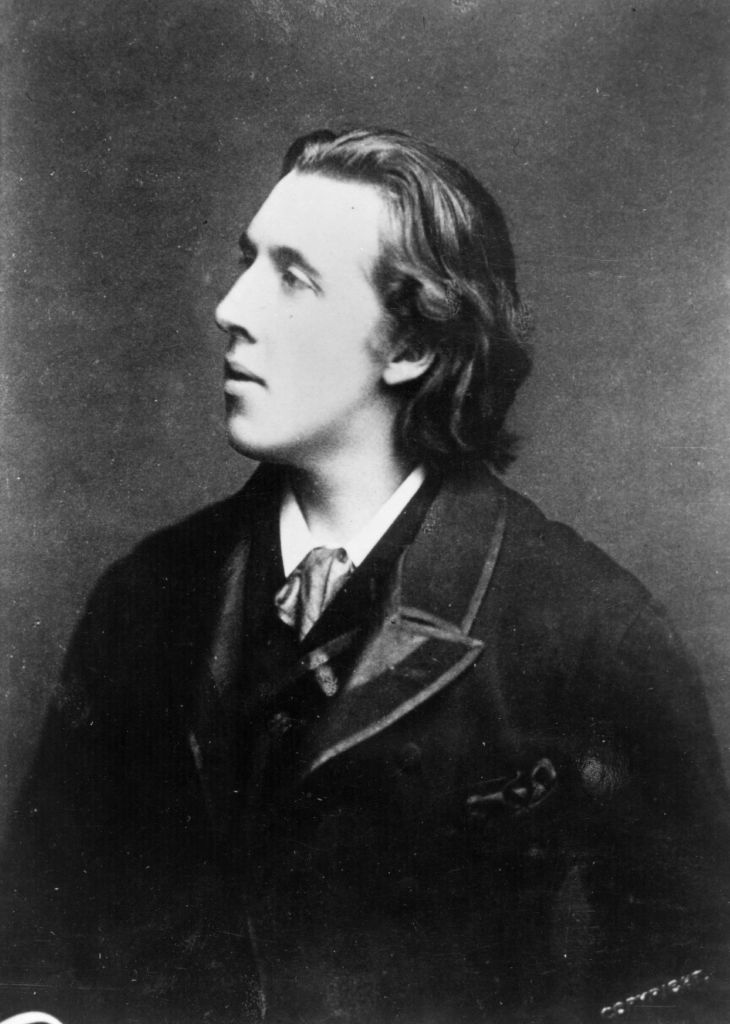

Oscar Wilde’s grandson on his trials and preserving his legacy: ‘It’s the young who will keep him alive’

Oscar Wilde’s grandson on his life, legacy and trials. (Getty Images/JOEL SAGET/AFP)

By the time Oscar Wilde died in November 1900, the literary world and wider society had done its best to forget all about him.

Victorian Britain was a harsh, punishing place to be queer, and Irish poet and playwright Wilde discovered that the hard way. The extraordinary life and career he had built for himself came crashing down when he became embroiled in a high-profile libel case with the Marquess of Queensberry, the father of his lover.

Queensberry famously left a calling card at Wilde’s London club in which he described him as a “posing sodomite”. Wilde took legal action – against the advice of many of his friends – and lost.

He was ultimately convicted of criminal charges and sentenced to hard labour. He died in Paris, aged just 46.

More than a century on, and Wilde’s infamous libel trial continues to create interest. It’s now the subject of Wondery’s British Scandal podcast series, which tells the story of the moral panic that surrounded Wilde and his affairs towards the end of his life.

Oscar Wilde’s grandson never got to meet him

Merlin Holland is Wilde’s grandson. While he never got to meet the man, he has dedicated much of his life to researching and writing about him, but there is one answer that still evades him: why did he instigate the libel case when he surely knew it could end in disaster?

“If we meet in the afterlife, it’s the first question I’ll ask him: why the hell did you do it?” Holland tells PinkNews.

“An awful lot of people at the time said: ‘Don’t, you’re mad. No jury is going to find against a father who is trying to protect his son’.”

But Wilde was in love, and he wanted to do whatever he could for his lover Lord Alfred Douglas – better known as Bosie.

“It was Bosie who was determined to get his father into trouble if not put behind bars,” Holland explains. “Oscar loved Bosie, he wanted to please him. He allowed himself to be pushed into doing this partly because of his love for Bosie.”

The ensuing trial was a spectacle, and Wilde was a willing participant. He seemed to see the whole thing as a “piece of theatre” and was trying to “play to the gallery”, but it wasn’t long before everything began to fall apart. It only gradually seems to have dawned on him that he was in trouble.

“It’s what he says in De Profundis [a book written by Wilde during his imprisonment in Reading jail]: danger was half the excitement. I think he courted danger in a way which is almost incomprehensible,” Holland adds.

The crucial slip that brought Oscar Wilde tumbling down

The first major blow in the trial came when Wilde was grilled on his friendships with young, working-class men. The writer insisted that he simply enjoyed the company of young men, telling the court that he didn’t believe in social barriers, but then came one slip that would go on to set the tone of the proceedings.

When asked if he had ever kissed a particular servant boy, Wilde replied: “Oh dear, no. He was a particularly plain boy – unfortunately ugly – I pitied him for it.”

It was a pivotal moment marked by Wilde’s characteristic wit and charm – but it was also a clear admission that he had paid attention to the young man’s looks.

“It’s the train with the light coming towards you at the end of the tunnel. There’s absolutely no escape from there on. I think he realises that things are getting seriously out of hand,” Holland says.

The trial eventually came grinding to a halt when the defence announced that they had found several male sex workers who would testify that they had slept with Wilde. Finally, he dropped his prosecution, Queensberry was cleared, and the court declared that the “posing sodomite” claim was “true in substance and in fact”.

But Wilde’s woes were far from over.

After leaving court, he was arrested on charges of sodomy and gross indecency. Jailing Wilde, the judge sentenced him to two years’ hard labour and declared that the penalty – the maximum allowed in such a case – was “totally inadequate”.

The public shunned Wilde and his legacy

In the years after his conviction, Wilde’s name was “hardly mentioned in polite society in England”, Holland says. People did their best to forget he had ever existed, although his work continued to enjoy popularity in Germany, France and Italy.

Wilde’s legacy continued to fluctuate massively in England in the decades after his death. There were moments when it appeared that his work would have the breakthrough it needed to make it back into the public consciousness, then the whole thing would falter.

It didn’t help that, in a separate – equally as infamous – trial in 1918, Bosie declared that Wilde was “the greatest force of evil” to have appeared in Europe in 350 years. For Wilde’s former lover to pillory his name in such a way only added insult to injury.

By the 1940s, there was some renewed interest in Wilde. H Montgomery Hyde published a book on the trial in 1948, but not everyone was impressed, with one reviewer condemning it for lifting the lid on a “Victorian sewer”.

Holland reveals: “I was three at the time. I obviously had no idea of anything at all. But I imagine my father reading a review like that in the newspaper and thinking, ‘This is my father. This is what it’s all been about’.”

Wilde’s reputation eventually recovered, of course. Public attitudes are radically different today to what they were in the 1890s when he found himself in the dock, and the laws under which he was convicted are no longer on the statute books.

Those changes helped pave the way for a re-evaluation of Wilde, his life and his work. Today, he’s seen by many as a martyr-like figure: somebody who died after being unfairly and savagely mistreated by the courts, the state and the public.

Holland is glad that his grandfather’s legacy has been pieced back together, even if it took a long time.

“Life goes very much in waves,” he says. “There was a time in the 1960s [when] his letters were published, and it’s at that moment people begin to see that, behind this two-dimensional cardboard facade of the funnyman, the writer of plays, the writer of children’s stories, suddenly he becomes a flesh-and-blood person.”

Much has changed, but Holland is always keenly aware that things could take a sudden turn for the worse again.

Wilde was a controversial figure in his lifetime, and his grandson sometimes worries that the writer of such classics as The Importance of Being Ernest and The Canterville Ghost, as well as children’s favourites, including a host of fairytales and The Selfish Giant, could go out of fashion again – that his work could be declared irrelevant.

As far as Holland sees it, that hasn’t happened because of young people around the world who continue to keep his legacy alive. It’s not just that they love his work, Holland says, it’s that they see him as an inspirational figure, a symbol of the fight against oppression and injustice.

“It’s the young who will keep him alive today because he represents to them a lot of the qualities I think they’d like to claim for themselves,” Holland says.

Wondery’s British Scandal podcast series focusing on Oscar Wilde is available from all major podcast providers now.

How did this story make you feel?